Spying fresh animal tracks in snow, the young girl—who would grow up to be famed Appalachian writer Wilma Dykeman—was consumed by curiosity: “How I ached when I was a child with that longing which borders on desperation, to follow some such animal of the woods and know its life,” Dykeman writes in her posthumously discovered memoir, Family of Earth: A Southern Mountain Childhood. “To see what it saw last night and as it saw; to hear the rustle of the falling snow and be aware of other sharp bright eyes peering through the darkness—this was what I wanted to know.”

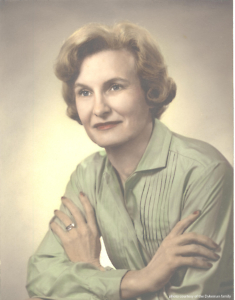

As an adult, Dykeman kept homes in both Asheville, North Carolina, and Newport, Tennessee. Over the course of her decades-long career, she became renowned for her prolific and varied body of work, which included several novels of Appalachian life, groundbreaking environmentalist writings, and essays of civil-rights advocacy. Her novels, especially The Tall Woman, are often cited as influences by contemporary Appalachian writers like Ron Rash, Lee Smith, and Robert Morgan, who provides a thoughtful foreword to this book. Dykeman wrote Family of Earth while she was still in her twenties, but it was not discovered until her death in 2006. The memoir details her childhood in the mountains around Asheville during the 1920s and ‘30s.

As an adult, Dykeman kept homes in both Asheville, North Carolina, and Newport, Tennessee. Over the course of her decades-long career, she became renowned for her prolific and varied body of work, which included several novels of Appalachian life, groundbreaking environmentalist writings, and essays of civil-rights advocacy. Her novels, especially The Tall Woman, are often cited as influences by contemporary Appalachian writers like Ron Rash, Lee Smith, and Robert Morgan, who provides a thoughtful foreword to this book. Dykeman wrote Family of Earth while she was still in her twenties, but it was not discovered until her death in 2006. The memoir details her childhood in the mountains around Asheville during the 1920s and ‘30s.

In describing these early memories, Dykeman’s emphasis often rests on small sensory details. Western North Carolina’s mountains could not provide a more abundant setting for a young writer’s developing eye. Feeding what she would later call “an appetite for imaginative living,” young Dykeman notices everything about the mountains around her, and then looks closer to see the ways in which those details work together: “The porch was covered thick with kudzu vine. As we sat there in the security of familiar voices, the summer moon shone full and near through the great leaves, scattering strange shapes which for all the world were like the hieroglyphs of some ancient, unknown language.”

She pays tender attention to the skills displayed by the adults who were closest to her. How her father sawed and hammered furniture in his workshop. How her grandmother corrected everyone’s grammar while piecing together complex quilting patterns. How her mother’s hands were adept at building fires. How the sounds of her aunt’s singing next door blended with the sounds of the nearby creek as they drifted through the windows of her own house.

One theme that emerges strongly in the book’s second half involves the interconnectedness of life and death. The narrative ends with the death of Dykeman’s father, which occurred just days after her fourteenth birthday. Whether she’s describing the farming of chickens or the passing of the seasons, the cyclical nature of the world—including the inevitability of death—looms large. She tries to make sense of mortality by mulling over her own orientation toward the natural world: “Feeling part of nature as I did, I could not always resist the human temptation to think of it as something created as a supplement to myself. Underneath, however, I think I always knew it was a life whole in itself, being neither supplement nor servant.”

One theme that emerges strongly in the book’s second half involves the interconnectedness of life and death. The narrative ends with the death of Dykeman’s father, which occurred just days after her fourteenth birthday. Whether she’s describing the farming of chickens or the passing of the seasons, the cyclical nature of the world—including the inevitability of death—looms large. She tries to make sense of mortality by mulling over her own orientation toward the natural world: “Feeling part of nature as I did, I could not always resist the human temptation to think of it as something created as a supplement to myself. Underneath, however, I think I always knew it was a life whole in itself, being neither supplement nor servant.”

As the book progresses, Dykeman reveals more complex attitudes toward human beings’ relationships with each other and with the vastness of the natural and spiritual universe around them—subjects which would come to define her later work’s aesthetic values. She considers the darker side of beauty and its necessity to a mature understanding of life. Numerous incidents in the book—both her own experiences and those of her parents—reveal a strong awareness of social inequities. Dykeman goes beyond a simple narration of her early life, arguing for compassion toward those around us who are most vulnerable.

Family of Earth is far more than a new discovery for literary scholars. The pleasures of reading this memoir stem from Dykeman’s fresh exploration of subjects that, on the surface, would seem the most familiar. In all things, she strikes a tone of honest wonderment. Hers is a large-hearted vision that embraces the paradoxes at work in the natural world and in human lives. To any reader who longs for a deep breath during this time of particularly loud cultural noise, Family of Earth may provide that much-needed meditation.

Emily Choate holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College. Her fiction has been published in The Florida Review, Tupelo Quarterly, and The Double Dealer, and her nonfiction has appeared in Yemassee, Late Night Library, and elsewhere. She lives in Nashville, where she’s working on a novel.

Tagged: Nonfiction