The Age of Enlightenment—a period generally encompassing the middle decades of the eighteenth century—saw amazing leaps in science and discovery. Thanks to the spread of the printing press and the role of shipping in creating world’s first global economy, all of Western civilization seemed engaged in a scientific quest to understand the heavens and the Earth. Naturalists discovered new species by the score. Telescopes looked outward toward a growing universe, even as new microscopes looked inward into the very cells of nature. Educated people everywhere were convinced that all scientific mysteries could be solved with careful observation and rational thought. “By any reasonable measure of achievement,” wrote the American biologist Edmund O. Wilson, “the faith of the Enlightenment thinkers in science was justified.”

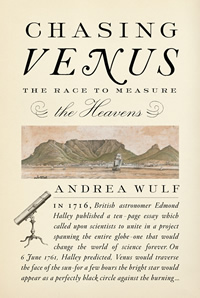

In Chasing Venus: The Race to Measure the Heavens Andrea Wulf, a writer best known for her histories of gardens and gardeners, examines a mostly forgotten event that not only illustrates the scientific curiosity of the age but may have played a part in bringing it about: an international quest to observe two rare transits of Venus across the face of the sun, in 1761 and 1769. The effort began with the English astronomer Edmond Halley in 1716, when he wrote an impassioned essay suggesting that the first accurate measurement of the size of the solar system could be achieved if astronomers simultaneously observed the pair of transits—which would not occur again for another 105 years—from many vantage points across the globe. By comparing the different viewing angles and exact times of the transit, the distances between Earth, Venus and the Sun could be calculated, and by extension the distances between all other known planets as well. But to reach the far-flung viewing locations, many nations and even the American colonies would have to outfit expensive expeditions, and the observers themselves would have to brave frozen wastes, tropical rainforests, battles at sea and on land, disease, suspicious villagers, piracy, and all the dangers a preindustrial world could present. The plan required a united international effort, Wulf writes, that would “change the world of science forever.”

Wulf presents a fascinating cast of characters who were intimately involved with the project. There are famous champions of science like Catherine the Great and Benjamin Franklin. There are young participants whose names would eventually become familiar, such as a pair of nervous surveyors named Mason and Dixon, later known for their line in America, and a young sea captain named James Cook, who is given a refitted coal transport called the Endeavor and ordered to sail an astronomical team to the South Pacific, where he and the ship would later redraw the British map. But the most memorable characters in Chasing Venus are the less familiar heroes of science from several nations, passionate investigators who charge into danger like Indiana Jones, sometimes giving their lives to bring their measurements of a short-lived solar event to the world.

Wulf presents a fascinating cast of characters who were intimately involved with the project. There are famous champions of science like Catherine the Great and Benjamin Franklin. There are young participants whose names would eventually become familiar, such as a pair of nervous surveyors named Mason and Dixon, later known for their line in America, and a young sea captain named James Cook, who is given a refitted coal transport called the Endeavor and ordered to sail an astronomical team to the South Pacific, where he and the ship would later redraw the British map. But the most memorable characters in Chasing Venus are the less familiar heroes of science from several nations, passionate investigators who charge into danger like Indiana Jones, sometimes giving their lives to bring their measurements of a short-lived solar event to the world.

Writing in a clean and precise style reminiscent of Dava Sobel’s Navigation and Holly Tucker’s Blood Work, Wulf nonetheless develops a narrative pace more typical of a globe-trotting thriller than a history book. Wulf follows events of the transit in chronological order—or as close to chronological as sometimes-simultaneous events can be covered: thus one expeditionary team is icebound on a tiny island at the northern tip of Norway while another builds the first European structure on Tahiti (and also discovers the islanders’ decidedly non-British attitudes toward sex). There are bloody sea battles and an attack by superstitious peasants convinced the astronomers are doing the devil’s work.

Stranded in Siberia during a 4,000-mile-trek to a remote viewing outpost, a French astronomer named Jean-Baptiste Chappe d’Auteroche refused to give up when an early thaw made a river unsafe to cross, threatening to keep him from meeting his transit appointment. “After all that he had endured, Chappe d’Auteroche refused to believe that the expedition had come to a halt so close to its goal,” Wulf writes. “He cajoled, bantered and bullied, trying to talk his companions into taking the risk. When he finally convinced them, with the help of copious amounts of brandy, it was night and so dark they could see only the faint glimmer of stars reflected in the treacherous ice. Although water had started to seep out over its thawing surface, Chappe hurried his drunken men along. Scared but determined, he stood on top of his sledge, driving his small expedition through the water across the thin ice.”

Stranded in Siberia during a 4,000-mile-trek to a remote viewing outpost, a French astronomer named Jean-Baptiste Chappe d’Auteroche refused to give up when an early thaw made a river unsafe to cross, threatening to keep him from meeting his transit appointment. “After all that he had endured, Chappe d’Auteroche refused to believe that the expedition had come to a halt so close to its goal,” Wulf writes. “He cajoled, bantered and bullied, trying to talk his companions into taking the risk. When he finally convinced them, with the help of copious amounts of brandy, it was night and so dark they could see only the faint glimmer of stars reflected in the treacherous ice. Although water had started to seep out over its thawing surface, Chappe hurried his drunken men along. Scared but determined, he stood on top of his sledge, driving his small expedition through the water across the thin ice.”

These moments of danger became the norm for many of the expeditions the book chronicles, and they keep the reader turning pages with an eagerness worthy of Wulf’s characters themselves. Chasing Venus presents the history of science at its most fascinating—and most adventurous.

Andrea Wulf will read from and discuss Chasing Venus at the Nashville Public Library on May 24, as part of the Salon@615 series. The event will begin with a reception at 6:15 p.m., followed by a reading at 6:45. Both are free and open to the public.

Tagged: Nonfiction