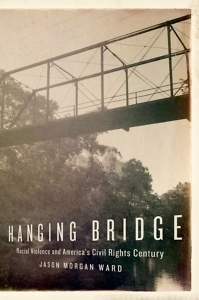

If you make your way down a closed-off road near Shubuta, Mississippi, you might find the old steel-framed bridge that spans the muddy Chickasawhay River. It is known in Clarke County as the Hanging Bridge. In 1918, a mob of whites lynched two young men and two pregnant women there. In 1942, another mob killed two boys there. In Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century, Jason Ward meticulously reconstructs the details of this horrific violence and artfully uses them as departure points to explain both Mississippi’s struggle for racial justice and the fierce resistance it engendered. Ward recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: Hanging Bridge considers a long span in the history of Clarke County, with a focus on the years 1918, 1942, and 1966. What do we gain from this “long” approach to the history of racial violence and civil rights?

Chapter 16: Hanging Bridge considers a long span in the history of Clarke County, with a focus on the years 1918, 1942, and 1966. What do we gain from this “long” approach to the history of racial violence and civil rights?

Jason Ward: My goal with the book’s structure was to capture and connect three moments of local violence and national change, and to devote roughly equal attention to three important eras in the twentieth-century black-freedom struggle. That is not to imply that nothing of equal significance occurred in the gaps between, and I certainly do not offer a progressive narrative of “how far we have come” or a depiction of a cohesive, multi-generational “movement” that spanned a century.

Yet the “long” view I provide is unique and useful because the Jim Crow era too often serves as a prologue to books on the civil-rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The World War I and World War II eras are immensely important and instructive in their own right, and the Hanging Bridge lynchings provided a structure for capturing those generational moments and trying to connect them to the movement and the violent opposition that emerged in the 1960s.

On a more practical level, I wanted a book that could give a sense of that sweep and complexity without being too long, too expensive, or too academic. I teach large lecture courses on Modern U.S. history in which I can only use two or three books on anything, which means maybe one civil-rights book. So a book that I can revisit three times across a semester is a rare and useful teaching tool.

Chapter 16: The first set of lynchings in Shubuta occurred during World War I. The second set occurred during World War II. Why did the war years precipitate this mob violence?

Ward: The most consistent forces at work in these eras are African Americans’ mobility and rising political influence. When investigators—in 1918 an undercover NAACP official, and in 1942 FBI agents and journalists—entered Clarke County during wartime, they discovered widespread anxiety about black migration and labor shortages. That anxiety was political in nature because migration and mobility undermined the isolation of their community and disrupted the racial status quo. When local whites complained that blacks were becoming “uppity” during the war, they were connecting their newfound prosperity and economic mobility to seemingly distant campaigns against lynching and disfranchisement or civil-rights debates on Capitol Hill.

Chapter 16: It is interesting to note the distinctions in political approaches among Mississippi whites, from hardliners such as James Vardaman and Theodore Bilbo to “moderates” such as the Mississippi Welfare League. From the perspective of black Mississippians, was there any difference?

Ward: One thing I learned from this project is that violence is the foundation for how we define variations in white racial politics. Certainly, it is important to understand that white supremacy was hard work and whites debated the most effective strategies for preserving Jim Crow. However, it is also important to remember that when we plot those leaders on a spectrum, we are essentially measuring how much distance they put between themselves and the constant, ever-present option of violence. This is why black Mississippians’ perspective is essential to this book—because activists and everyday people recognized that if they pushed hard enough they would eventually encounter violence. And they did, even after lynching had seemingly disappeared.

Chapter 16: There were no murders on the Hanging Bridge in 1966, the subject of your book’s third section. How did the bridge figure into the story of the civil-rights movement in Clarke County?

Chapter 16: There were no murders on the Hanging Bridge in 1966, the subject of your book’s third section. How did the bridge figure into the story of the civil-rights movement in Clarke County?

Ward: Part III (1966) is essential to the book’s argument because I wanted to see what effect the memory of Jim Crow-era violence had on local people during the civil-rights era. What I discovered is that the bridge, which still spanned the Chickasawhay River in 1966, affected how local people defined the stakes and the risks of a local movement. It did not stop them, but they certainly believed another round of lynchings was possible. While the fact that no one died at the bridge in the 1960s might tempt the reader to conclude that racial violence had evolved or diminished, local whites still responded violently to the threats posed by local civil-rights activity. And local people were still reckoning with the implications of violence—the ravages of poverty, the morality of the Vietnam War, and the unrest on college campuses and in urban ghettoes—far beyond rural Mississippi.

Chapter 16: By the late 1960s, federal antipoverty funding served as a key battleground in Clarke County’s civil-rights movement. Why?

Ward: As I mentioned before, black economic mobility was the most consistent predictor of violence that I found in my research. Put more bluntly, in moments when whites were complaining about black women leaving their kitchens for better-paying work, violence followed. When Head Start came to Clarke County, and black women suddenly wielded economic leverage and exerted economic independence through federal funds that whites could not control, that sparked greater resentment than the voter-registration drives and sit-ins of the previous year. And when civil-rights activists and Head Start workers launched a boycott of white merchants in Shubuta, the town nearest the Hanging Bridge, a white mob attacked them, and local officials successfully lobbied to have the local Head Start agency defunded.

Chapter 16: What is the contemporary relevance for Hanging Bridge? How might it help us understand our current predicaments?

Ward: I did not write this book in response to something I saw on cable news, but I wrote the book in an era where I encountered a steady stream of reminders that racial violence is still with us and the ways in which we rationalize it are not terribly different than they were seventy-five or 100 years ago. For example, when Northern reporters and FBI agents descended on Clarke County after the 1942 double lynching of a fourteen- and fifteen-year-old, local whites repeatedly insisted that the boys were several years older, or at least appeared several years older, than they actually were. When I hear the same rationalizations applied to the Trayvon Martin or Tamir Rice cases, I certainly cannot help but hear the echoes of history.

Aram Goudsouzian chairs the history department at the University of Memphis. His most recent book is Down to the Crossroads: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Meredith March Against Fear.