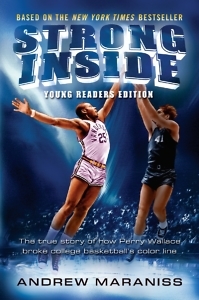

Andrew Maraniss has seen his passion project—the story of Perry Wallace, the Vanderbilt basketball player who broke the color barrier in Southeastern Conference athletics—grow into a cottage industry. His book, Strong Inside, which took eight years for Maraniss to research and write, was published by Vanderbilt University Press in 2014 to widespread acclaim and impressive sales. (It was the first book in the history of the press to reach The New York Times bestseller list.) The biography gained further notoriety by winning the Lillian Smith Book Award, which recognizes books that promote racial and social justice, and by earning special recognition from the Robert F. Kennedy Book Awards. Since then, Maraniss and Wallace have made media appearances around the country, including interviews on ESPN and NPR, bringing Wallace back into the spotlight in time for fiftieth anniversary commemorations of the civil rights movement.

Maraniss, a 1992 Vanderbilt graduate, has been especially gratified by the Vanderbilt community’s response. Last fall Strong Inside was the Commons Reading book for incoming freshmen, and Maraniss and Wallace have spoken at several events on campus. Most recently Wallace appeared alongside former teammate Godfrey Dillard as part of the university’s James Lawson Lecture, and the book was featured prominently in Vanderbilt’s Fine Arts Gallery at an exhibit titled Race, Sports and Vanderbilt 1966-1970. Fellow alumni from Wallace’s generation recently raised money to endow the Perry E. Wallace Jr. Scholarship for an undergraduate in the School of Engineering, as well.

Maraniss, a 1992 Vanderbilt graduate, has been especially gratified by the Vanderbilt community’s response. Last fall Strong Inside was the Commons Reading book for incoming freshmen, and Maraniss and Wallace have spoken at several events on campus. Most recently Wallace appeared alongside former teammate Godfrey Dillard as part of the university’s James Lawson Lecture, and the book was featured prominently in Vanderbilt’s Fine Arts Gallery at an exhibit titled Race, Sports and Vanderbilt 1966-1970. Fellow alumni from Wallace’s generation recently raised money to endow the Perry E. Wallace Jr. Scholarship for an undergraduate in the School of Engineering, as well.

A year after its initial publication, Maraniss began to work on an edition of Strong Inside for readers ages ten to fourteen. The new edition, which is one-fifth the length of the adult version, retains the full arc of Wallace’s story, from his north Nashville upbringing through his career as a law professor. Crucially, Maraniss did not soften his portrayal of the injustice and abuse Wallace endured during his playing days in the SEC. Maraniss recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email:

Chapter 16: In the acknowledgments page of the young-readers edition, you credit novelist Ruta Sepetys (whom you ran into in a Nashville coffee shop) with encouraging you to create this version of Strong Inside. How did this edition get off the ground?

Andrew Maraniss: The idea of adapting Strong Inside for young readers was something I had only vaguely considered until I met Ruta. She was incredibly enthusiastic about the idea and introduced me to her publisher, Penguin’s young-readers imprint, Philomel. Michael Green there told me that he was looking for stories about unsung sports figures and also had an interest in race, so I was fortunate to have a story that was in line with what he was seeking to publish. After reading the adult version, he told me it would need to be cut significantly but not dumbed-down, which I was happy to hear. Brian Geffen was my editor during that process, and he and I worked together really well. It was actually an enjoyable experience cutting a 200,000 word book down to 40,000 words and having it still maintain tension and drama and make sense.

Chapter 16: Surprising, gratifying, or weird: what have been your most remarkable experiences since Strong Inside was first published?

Maraniss: Surprising: having a freshman from Shanghai tell me that he decided to come to the U.S. and study at Vanderbilt after reading the book. He said if Perry Wallace could make it at Vanderbilt, he could, too.

Gratifying: seeing the incredibly warm—and overdue—reception Perry Wallace and Godfrey Dillard have received from Vanderbilt and from the city of Nashville since the book came out. They were heroes who were overlooked for nearly a half-century, but now they feel the love they’ve deserved for so long.

Weird: not so much weird, but many surreal experiences. Being on a panel at the National Civil Rights Museum on MLK Weekend with the likes of NBA stars Earl the Pearl Monroe, Vince Carter, Chauncey Billups, and Sam Moore from Sam and Dave. Sitting in the green room at Meet the Press and meeting Andrea Mitchell and David Brooks, who were also guests that day, and later walking through Times Square, holding my book, on the way to a live interview with Keith Olbermann for ESPN. And having a chance to accept an award for the book from the RFK Human Rights Center, and to look out and see Ethel and Kerry Kennedy sitting in the front row.

Chapter 16: The young-readers edition covers most of the events you write about in the original book but in substantially fewer pages. What were the most difficult parts for you to leave out?

Maraniss: At first, making any cuts at all was something I dreaded doing. I felt so attached to the original book, which was a project I worked on for eight years. But soon the editing became a really enjoyable exercise—fine-tuning, fine-tuning, fine-tuning. The most difficult parts to leave out entirely were some of the side stories about tangential characters, places, and events. These were stories that added richness to the narrative but weren’t essential to understanding Perry Wallace’s journey. So it made sense to cut them, but they were all stories I was attached to in one way or another.

Chapter 16: On a similar note, what content changes did you make out of consideration for a younger audience? In a note to young readers, you warn that you have not “sanitized” the racial epithets, yet the most harrowing scenes are also less relentlessly detailed.

Chapter 16: On a similar note, what content changes did you make out of consideration for a younger audience? In a note to young readers, you warn that you have not “sanitized” the racial epithets, yet the most harrowing scenes are also less relentlessly detailed.

Maraniss: To the extent that any scenes are shorter, it was merely in an effort to tell the story under the prescribed word count, and not to whitewash or eliminate any especially painful episodes of racism. In both the adult version and the middle-grade version, it was important to me that the reader is able to put themselves in Perry Wallace’s shoes and experience the same discrimination, hate, and isolation that he felt. I think that’s the only way a reader can gain true empathy and understanding.

The changes that were made specifically because of the younger audience for this adaption were things like adding cliffhanger types of sentences at the end of chapters to keep young people interested in continuing the story, or adding some additional explanation for people or events that aren’t top-of-mind for 10 year-olds (who was Emmett Till?). Again, the direction I received was to respect young readers and not over simplify the copy.

Also, given the racial divide in this country and the incidents of school bullying and harassment we’ve seen since the election, I am hopeful this book can play a small role in bringing kids together. Some young readers will identify closely with Perry Wallace and the challenges he faced and gain inspiration from his courage and accomplishments. But just as important to me is that kids who might not identify with Perry in obvious ways will also find that the book leads them to greater feelings of empathy and understanding and motivates them to be more socially conscious.

Chapter 16: Of all the events you describe in Strong Inside, the one I would most want to time-travel to would be the game between Pearl High School and Father Ryan in January 1965, the first integrated basketball game in Nashville. If you could choose one day of Wallace’s life to experience yourself, which would it be?

Maraniss: There are so many amazing, once-in-a-lifetime scenes in the book that I would love to experience for myself, including that Father Ryan-Pearl game and the 1966 Tennessee high school basketball championship game, which took place on the same night as the famous Texas Western—Kentucky NCAA title game of Glory Road fame. But if I had to pick one event, it wouldn’t involve basketball. It would be the 1967 Impact Symposium at Memorial Gym at Vanderbilt, where you had Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, Strom Thurmond, and Allen Ginsberg speak to sold-out crowds over the course of about twenty-four hours. I can’t imagine a more compressed window into all the interesting facets of the 1960s than that one event.

Chapter 16: Your book describes Wallace’s personal and intellectual qualities in great detail, but he was also a remarkable athlete. What set him apart as a basketball player?

Maraniss: Perry Wallace was a tremendous shot-blocker, rebounder, and dunker. It was his dunking ability that allowed him to fit in with the guys as a middle-school and high-school player, when otherwise he may have been considered a bit of a bookworm. He was a tremendous leaper. On a high- school team where every single player could dunk, they would save Perry for last in warm-ups, and he’d bring down the house with his artistic and powerful dunks. The slam dunk was outlawed in college basketball during Perry’s time at Vanderbilt, however, a rules change that had obvious racial undertones. The last basket of Perry Wallace’s career was an “illegal” slam dunk against Mississippi State. He said this was his form of protest on his way out. It was incredibly symbolic of the injustices he had overcome.

Chapter 16: When Wallace parted with Vanderbilt in 1970, his relationship with the university was strained, though not acrimonious (as it was for Godfrey Dillard). Any sense of how Wallace feels about Vanderbilt now?

Maraniss: Perry Wallace’s relationship with Vanderbilt now is better than it has ever been. Vanderbilt has a program where all incoming freshmen read the same book, and this year the book was Strong Inside. Because of that, the university created several really interesting programs—including art exhibitions, spoken word performances, and campus tours—related to the book. Perry Wallace and Godfrey Dillard were invited back to campus to meet with the current generation of students, and the interactions were powerful. Perry told me if he were to put a bumper sticker on his car, it wouldn’t be a Columbia Law sticker but a Vanderbilt one. He is proud of the progress made at the school in the area of diversity and inclusion.

It may also surprise you that Godfrey Dillard also feels good about Vanderbilt. When he met with students at Vanderbilt’s Black Cultural Center this fall, he became very emotional and said that for the very first time, he felt like what he did here as a young man was worth it. It was quite a scene. At dinner later that night, he proposed a toast to Chancellor Zeppos in recognition of the changes at Vanderbilt.

Chapter 16: After having spent so many hours with Perry Wallace, and so much of your own life writing his story, what impact would you say he’s had on you personally?

Maraniss: Perry Wallace has been a big part of my life for more than half of my life. The first time I wrote a paper about Perry in college, I was nineteen years old. Now I’m forty-six. I spent eight years writing the original book and another year creating the young-readers version. In some ways I feel like my reason for being, at least in an academic and professional sense, has been to tell his story. I was born about a week before he played his last game at Vanderbilt, which I’ve always found symbolic in some way.

Perry is a brilliant person who is always thinking several steps ahead of any circumstance and sees the big picture. He’s a law professor today and a teacher at heart. I think it gives him pleasure to share his wisdom with others, to nurture young people, and I have been fortunate to be on the receiving end of that generosity of spirit for decades. My kids are now six and three, and they’ve gotten to know him, too. He came to visit our house and they started running around and jumping up and down, yelling “Perry Wallace, Perry Wallace, Perry Wallace!” That was kind of a full-circle moment for me and made me very happy.

Sean Kinch grew up in Austin and attended Stanford. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of Texas. He now teaches English at Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville.

Tagged: 2017 Southern Festival of Books, Andrew Maraniss, Children & YA, Nonfiction