Colin Powell’s résumé is one of the most remarkable in America. Graduating from the ROTC program at City College of New York in 1958, he entered the Army as a second lieutenant in the infantry and served two tours in Vietnam, where he was wounded in action. After a meteoric rise through the ranks, he retired in 1993 as a four-star general, having become the first ROTC graduate, the youngest officer, and the first—and so far only—African American to serve as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. And that was just his military career.

Named a White House Fellow by President Richard Nixon in 1972, Powell went on to serve in four more administrations; as national security advisor to Ronald Reagan, as chairman of the joint chiefs—the president’s primary military advisor—under George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton, and finally as secretary of state for George W. Bush. Outside government, his service has been distinguished by, among other things, his work with America’s Promise Alliance, a foundation dedicated to helping children from all backgrounds. A full listing of Powell’s accomplishments and awards could fill the entire space allotted for this review without even touching on his work as an author of four books.

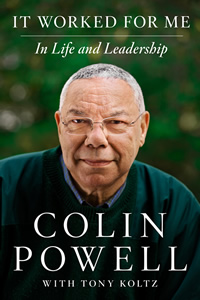

Powell has spent over a half century as a leader. Now he wants to share the lessons he learned in all those years of working to inspire and manage people. In his latest book, It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership, he passes along words of wisdom that would normally be handed down in private conversations between mentor and protégé. Beginning with “Thirteen Rules” and proceeding through sections with titles like “Know Yourself, Be Yourself” and “Getting to 150 Percent,” he gives advice by offering examples from his own experience. Each chapter is built on specific incidents during his rise from a young second lieutenant to an elder statesman.

Powell’s love for the stories he has accumulated is obvious, and they can at times seem too self-referential. But as full of the pronoun “I” as they are, the stories are just as often heavy with praise for others—from those who gave him his start in life to others who taught him how to lead. Because of his background, his examples come almost exclusively from military or government service, but he carefully explains how they should apply to any good manager in the private sector. In a chapter about correcting mistakes, he notes, “These truths are known to every good classroom teacher, every good coach, every good violin teacher, every good parent, and every good construction foreman.”

Powell’s love for the stories he has accumulated is obvious, and they can at times seem too self-referential. But as full of the pronoun “I” as they are, the stories are just as often heavy with praise for others—from those who gave him his start in life to others who taught him how to lead. Because of his background, his examples come almost exclusively from military or government service, but he carefully explains how they should apply to any good manager in the private sector. In a chapter about correcting mistakes, he notes, “These truths are known to every good classroom teacher, every good coach, every good violin teacher, every good parent, and every good construction foreman.”

Powell acknowledges making many mistakes in his long career, and he includes some of them as examples of how to learn from failures. In a section titled “Reflections,” the general finally addresses the elephant in the room, the mistake of all mistakes, which happened on a date, he writes, that “is as burned into my memory as my own birthday.” On February 5, 2003, acting as secretary of state for George W. Bush, Powell stood before the United Nations Security Council and laid out America’s case against Saddam Hussein. It was a powerful, effective speech that turned out to be dead wrong in its most important aspect: the claim that Saddam possessed an arsenal of weapons of mass destruction. Here was one of America’s most trusted leaders apparently forgetting that “You can’t make good decisions unless you have good information and can separate facts from opinions and speculation.”

This horrific mistake, which Powell admits is a “blot” on his record, is one for which he accepts responsibility but for which he is also quick to share blame. His questions about the veracity of the information were not answered completely, he writes, and some officials withheld their concerns about the intelligence sources. It is clearly, nine years later, an open wound—for both Powell and America: “I have never before written my account of the events surrounding my 2003 UN speech,” he writes. “I’ll probably never write another.”

The bitterness over intelligence failures notwithstanding, It Worked for Me is an upbeat, friendly book, a lucid primer on leadership. The lessons are both broad and specific and are written with such a personal touch that it often seems as if Powell is actually talking with the reader, recounting his love of restoring old Volvos or his pet peeves about hotels. (“Please, oh please, don’t get fancy shower controls with handles that give you no clue how to turn it, push it, or pull it on and off.”) Colin Powell is clearly a man full of hope and optimism, both for himself and his country. But he is also a man who has experienced the worst the world can offer, and his views are tempered by that truth: “I try to be an optimist, but I try not to be stupid,” he writes. That’s some very good advice, generally speaking.

Colin Powell will discuss It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership, in an onstage conversation with former Newsweek editor Jon Meacham on May 30 at 7 p.m. at Belmont University’s Massey Concert Hall. The event is part of the Salon@615 series.

Tagged: Nonfiction