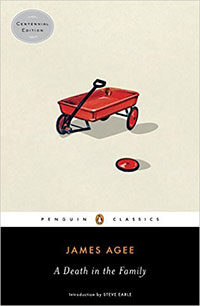

I first read “Knoxville: Summer 1915,” the prologue to James Agee’s A Death in the Family, on a spring evening, lying in my bed in a rural East Tennessee neighborhood much like the one Agee describes. My window was open for the first time after a long winter. I could hear the peepers at the creek down the hill, the crickets in the grasses, the barking of dogs, the voices of children playing in the safe dark. I could hear Agee’s voice inside me, too. I was born with it there. His is the voice of the men of my life: my father, my grandfathers, my uncles. Tennessee men, country men, who knew evenings, neighborhoods, and houses like the one Agee writes about, “where mothers in kitchens wash and dry and put things away, re-crossing their traceless footsteps like the lifetime journeys of bees.”

Readers often assume that James Agee is an influence of mine, and I’ve done little to disabuse them of the notion. For the longest time, I kept a guilty secret: I’d read pieces of A Death in the Family but not the whole. I have been influenced, though, by Agee through the writers he influenced. It’s easy to compare A Death in the Family to Cormac McCarthy’s Knoxville novel, Suttree, one I turn to again and again for literary inspiration. Agee and McCarthy are two men writing from two different eras who capture in words the same sense of the tight-knit community and the gritty underbelly of a country town. Both novels seem to me also like love letters to home, written from places of longing.

Readers often assume that James Agee is an influence of mine, and I’ve done little to disabuse them of the notion. For the longest time, I kept a guilty secret: I’d read pieces of A Death in the Family but not the whole. I have been influenced, though, by Agee through the writers he influenced. It’s easy to compare A Death in the Family to Cormac McCarthy’s Knoxville novel, Suttree, one I turn to again and again for literary inspiration. Agee and McCarthy are two men writing from two different eras who capture in words the same sense of the tight-knit community and the gritty underbelly of a country town. Both novels seem to me also like love letters to home, written from places of longing.

But I’m not sorry to have discovered A Death in the Family at the age of forty because I might not have appreciated it the same way earlier. Readers of a certain age may recognize Agee’s struggle in a way the young cannot—the struggle to capture memory, to convey the ache in the chest certain memories bring, “to ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth.” It wouldn’t be a stretch to assume the author is speaking of himself when he writes of his protagonist, Jay Follett: “[M]emory, almost captured, unrecapturable, unbearably tormented him.”

A Death in the Family is a book perhaps for those of us with decades to look back on, for the homesick among us trying to get at something but also back to something. As Jay travels across the river, away from Knoxville toward his rural birthright, he begins to feel his origins drawing him backward in time: “This was the real, old, deep country now. Home country.” Perhaps all writers who are, like Agee, rooted so deeply in place, who are so shaped by where they were born, suffer from a similar desperate desire to return to their sources of authenticity, to tell something true in fiction about where they’re from.

But Agee isn’t striving in the pages of his novel only to recapture or resurrect a specific time or place. He’s writing ghosts back to life. There is a literal haunting in A Death in the Family: on the night Jay Follett dies on the road, his wife Mary feels his presence in their house. Agee seems to suggest that even in death all is not lost. He seems to ask what we can keep of the life that passes away from us, what residue we might save, if only in the pages of a book. Mary whispers to the ghost of her husband, “Be with us all you can.” I imagine that for Agee, as much as anything, writing was a means of holding on.

But Agee isn’t striving in the pages of his novel only to recapture or resurrect a specific time or place. He’s writing ghosts back to life. There is a literal haunting in A Death in the Family: on the night Jay Follett dies on the road, his wife Mary feels his presence in their house. Agee seems to suggest that even in death all is not lost. He seems to ask what we can keep of the life that passes away from us, what residue we might save, if only in the pages of a book. Mary whispers to the ghost of her husband, “Be with us all you can.” I imagine that for Agee, as much as anything, writing was a means of holding on.

Agee asks us as well to sit with death, to rest in it, and the moment when Jay’s son Rufus stands over his corpse is almost too painful for the reader—at least this reader—to endure. I was tempted to skim over that wrenching passage, but I didn’t let myself. Most of us will come to this moment, if we haven’t already. We will inevitably stand over the coffins of our fathers. This is one of the truths James Agee tells us, part of the loss and darkness and homesickness he has captured in his haunted house of a posthumous book.

In what might be the most powerful scene of A Death in the Family, Rufus stands beside his dead father’s chair, lingering in “the cold smell of tobacco and high along the back, a faint smell of hair.” He runs his fingers inside the ashtray and comes up with “only a dim smudge of ash. There was nothing like enough to keep in his pocket or wrapped up in a paper. He looked at his finger for a moment and licked it; his tongue tasted of darkness.” There are just these traces of what we’ve lost, but we keep what we can, however we can. For James Agee, and for me, writing can be an act of preservation.

In the end, A Death in the Family does circle back around to place. It begins in a rural neighborhood captured in such luminous prose that a reader can smell the cut grass, and it ends with Rufus and his Uncle Andrew “standing at the edge of Fort Sanders and looking out across the waste of briars and embanked clay.” Rufus’s mind is a cauldron of bittersweetness swirling around home and family: “[T]hey love him, but he hates them … but he doesn’t hate them, really. But how can he love them if he hates them so?” I have asked this of myself, about my people and my place in the world. How do you love somewhere and hate it at once? We keep trying to work it out, to write it out, and we may never make sense of it, but that doesn’t stop our attempt to figure out our relationship to these hills and our people, our ties to this East Tennessee that formed us. For all of A Death in the Family’s lyricism, Agee sums it up at last in five simple words. “It’s time to go home.”

Novelist Amy Greene is the New York Times-bestselling author of Bloodroot and Long Man. Her third novel, The Nature of Fire, is forthcoming from Knopf. Greene lives with her family in the Tennessee foothills of the Smoky Mountains.

This essay is part of the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prize board and the Federation of State Humanities Council in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. For their generous support of the Campfires Initiative, we thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes board, and Columbia University.

Tagged: Fiction, Pulitzer100