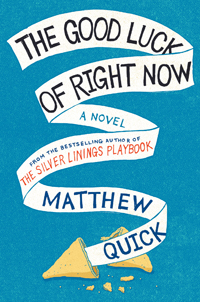

What if the only thing that made your life bearable was pretending that it was? “Pretending has always been easy for me. I have pretended my entire life,” says thirty-nine-year-old Bartholomew Neil, the protagonist of the new novel from Matthew Quick, author of The Silver Linings Playbook, a New York Times bestseller. The story of The Good Luck of Right Now unfolds in a series of letters from Bartholomew to his late mother’s favorite movie star, Richard Gere. Bartholomew has little in common with his pen-pal: “I’m six foot three inches tall with too much hair on my arms and in my ears, but not enough on the top of my head,” he writes. “People are often afraid of me when I get agitated or angry. But I’ve never ever hurt anyone—even in school when people used to shove me and call me a retard.”

Although Wendy, Bartholomew’s grief-counselor-in-training, describes him as emotionally disturbed and developmentally stunted—the result of a long-term codependent relationship with his recently deceased mother— Bartholomew’s letters reveal a sensitive and introspective man for whom life is often confusing. He has never held a job, but at the public library he studies the philosophies of Karl Jung and the Dalai Lama while trying to gather his courage to talk to a pretty library volunteer, the one he’s dubbed “The Girlbrarian.” It’s been three years, and he still hasn’t approached her, but he loves to watch the careful way she shelves books: “She’d slide the book back onto the shelf,” he writes, “make sure the spine was even with all of the other spines, and then give the top a little tap with her index finger, as if to say, ‘Perfect.’” Encouraged by Wendy, he also wants to seek out “age-appropriate activities with a peer”—perhaps enjoy a beer at a bar with a friend.

Although Wendy, Bartholomew’s grief-counselor-in-training, describes him as emotionally disturbed and developmentally stunted—the result of a long-term codependent relationship with his recently deceased mother— Bartholomew’s letters reveal a sensitive and introspective man for whom life is often confusing. He has never held a job, but at the public library he studies the philosophies of Karl Jung and the Dalai Lama while trying to gather his courage to talk to a pretty library volunteer, the one he’s dubbed “The Girlbrarian.” It’s been three years, and he still hasn’t approached her, but he loves to watch the careful way she shelves books: “She’d slide the book back onto the shelf,” he writes, “make sure the spine was even with all of the other spines, and then give the top a little tap with her index finger, as if to say, ‘Perfect.’” Encouraged by Wendy, he also wants to seek out “age-appropriate activities with a peer”—perhaps enjoy a beer at a bar with a friend.

But Bartholomew is short on both courage and friends, unless you count Father McNamee, his parish priest. When Bartholomew’s home is vandalized, Father McNamee comes to the rescue, organizing a group of parishioners to help clean up the mess. The volunteers turn the violation into a party, drinking wine as they work all night and celebrating with breakfast in the morning. The incident is a prime example of a lesson Bartholomew’s mother has instilled in him: “Whenever something bad happens to us, something good happens—often to someone else,” she says. “And that’s The Good Luck of Right Now.” And so Bartholomew often tries to imagine what good things are happening to counteract the misery of his own life: “Maybe a young woman in Tokyo would meet the love of her life when she jogged into the driver’s-side door of a slow-moving car because she was singing with her eyes closed and her future soul mate would be driving and feel so bad about the bizarre accident, he would ask her to have coffee,” he suggests, or “maybe a sun-sized asteroid headed for Earth would be pushed off course by an exploding star and would no longer end humankind seven thousand light years from now.”

Richard Gere enters Bartholomew’s life in much the same way. During his mother’s battle with brain cancer, she begins to call him “Richard.” Believing that she has mistaken him for her favorite actor, Bartholomew adopts that persona to bring her comfort, but the pretense soon becomes a way to accommodate the sudden changes in his own life. “Bartholomew had been working overtime as his mother’s son for almost four decades. Bartholomew had been emotionally skinned alive, beheaded, and crucified upside down, just like his apostle namesake,” he explains in a letter to Gere. “Being Richard Gere was like pushing my own mental morphine pain pump. I was a better man when I was you—more confident, in control, surer of myself than I have ever been.”

Richard Gere enters Bartholomew’s life in much the same way. During his mother’s battle with brain cancer, she begins to call him “Richard.” Believing that she has mistaken him for her favorite actor, Bartholomew adopts that persona to bring her comfort, but the pretense soon becomes a way to accommodate the sudden changes in his own life. “Bartholomew had been working overtime as his mother’s son for almost four decades. Bartholomew had been emotionally skinned alive, beheaded, and crucified upside down, just like his apostle namesake,” he explains in a letter to Gere. “Being Richard Gere was like pushing my own mental morphine pain pump. I was a better man when I was you—more confident, in control, surer of myself than I have ever been.”

As Bartholomew works through his grief, he encounters new characters who are so surprising and delightful that it would spoil the story to reveal them here. Suffice to say that they lead Bartholomew to make some startling discoveries about his own life, learn a lot about alien abduction, visit Cat Parliament, and gaze upon the heart of Saint Brother André and the brain of President James A. Garfield’s assassin. As his world expands in unexpected ways, he writes, “I am not more beautiful than I was when Mom was alive, but I feel as though I am a fist opening, a flower blooming, a match ignited, a beautiful mane of hair loosened from a bun—that so many things previously impossible are now possible.”

Somewhat reminiscent of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, The Good Luck of Right Now is a gentle, wise, poignant, and funny story about the nature of reality and the daily strength required of the brokenhearted to live in it. Quick makes no misstep; each scene, each character, each storyline is perfectly realized and seamlessly woven into the narrative. And Richard Gere hovers over the whole oddball world like a ministering angel, not only inspiring Bartholomew to achieve his heart’s desires, but revealing—just by listening—the incredible courage each struggle requires.

A delight from beginning to end, The Good Luck of Right Now is filled with quirky and unlikely characters whose pain and longing are so real that we celebrate each small step they take toward something like wholeness. Each one pretends what is necessary to withstand an unbearable present—whether the result of past choices they regret, circumstances they are powerless to change, or bad bargains they feel forced to make. As Bartholomew writes, “Believing—or maybe even pretending—made you feel better about what had happened, regardless of what was true and what wasn’t. And what is reality, if it isn’t how we feel about things?”

Matthew Quick will discuss The Good Luck of Right Now at Parnassus Books in Nashville on February 24, 2014, at 6:30 p.m.

Tagged: Fiction