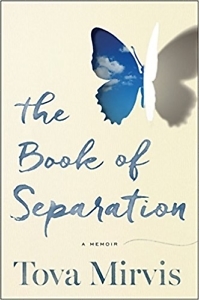

Youthful marriage, disillusionment, unhappiness, divorce—this personal journey is so common it’s a cliché. But for novelist Tova Mirvis, ending a long marriage cost more than the usual pain and upheaval. For her, divorce meant the loss of a faith identity and a way of being in the world. As an Orthodox Jew, Mirvis was taught from childhood that being a good wife and mother was her sacred duty, and her whole existence was shaped and bound by religious law. In her new memoir, The Book of Separation, she recalls her long struggle to reconcile herself to Orthodox life and her ultimate decision to leave her marriage and her faith community.

Mirvis, whose novels include The Ladies Auxiliary and Visible City, grew up in Memphis, the daughter of Modern Orthodox Jews who closely followed religious rules but didn’t separate themselves from the secular world. The many restrictions of Orthodox life—keeping kosher, dressing modestly, Shabbat observance, separation of the sexes—were unquestioned in her family, as were traditional gender roles, although Mirvis’s mother embraced a kind of “limited feminism” that sidestepped the issue of sexism within the faith. Mirvis chafed at the unfairness of some of the rules imposed on girls, but she was not inclined to rebel. As she describes it, her acquiescence was motivated as much by devotion to her people as by devotion to God: “There was one truth I knew without having to be told, not just in my family but in my community, among everyone that I knew: to observe was to be good, and to be good was to be loved.”

Mirvis, whose novels include The Ladies Auxiliary and Visible City, grew up in Memphis, the daughter of Modern Orthodox Jews who closely followed religious rules but didn’t separate themselves from the secular world. The many restrictions of Orthodox life—keeping kosher, dressing modestly, Shabbat observance, separation of the sexes—were unquestioned in her family, as were traditional gender roles, although Mirvis’s mother embraced a kind of “limited feminism” that sidestepped the issue of sexism within the faith. Mirvis chafed at the unfairness of some of the rules imposed on girls, but she was not inclined to rebel. As she describes it, her acquiescence was motivated as much by devotion to her people as by devotion to God: “There was one truth I knew without having to be told, not just in my family but in my community, among everyone that I knew: to observe was to be good, and to be good was to be loved.”

A post-high school year of study in Israel ushered in a fresh understanding of the faith for Mirvis, and she learned to see each rule as “a load-bearing wall in the over-arching structure,” but by the time she became engaged to a college boyfriend, doubts and discomfort had begun to return. She worked, as her mother had, to find a way around the conflict between what Orthodoxy demanded and what she felt.

This seemed doable to her youthful self. “Contradictions would persist,” she recalls thinking, “but it was possible to live with competing beliefs.”

That turned out not to be true, and as she approached her forties, Mirvis, who had settled in a Boston suburb with her husband and three children, chose to leave her marriage and, little by little, to abandon Orthodox observance. Some of the most interesting passages in The Book of Separation describe the disorienting, sometimes frightening process of learning to live without the reliable ritual and order her religious practice had always provided. On her first Rosh Hashanah after the divorce, she finds herself speeding through traffic as sundown approaches, something that would have been unthinkable just a short time before. In spite of her joy in a newly liberated life, she imagines her past literally catching up with her. “In my mind, there is a stampede of feet, the incessant thrumming of voices: She was driving on Rosh Hashanah, they say. We thought she was one of us.”

That turned out not to be true, and as she approached her forties, Mirvis, who had settled in a Boston suburb with her husband and three children, chose to leave her marriage and, little by little, to abandon Orthodox observance. Some of the most interesting passages in The Book of Separation describe the disorienting, sometimes frightening process of learning to live without the reliable ritual and order her religious practice had always provided. On her first Rosh Hashanah after the divorce, she finds herself speeding through traffic as sundown approaches, something that would have been unthinkable just a short time before. In spite of her joy in a newly liberated life, she imagines her past literally catching up with her. “In my mind, there is a stampede of feet, the incessant thrumming of voices: She was driving on Rosh Hashanah, they say. We thought she was one of us.”

There’s a level on which Mirvis’s experience will be alien to most readers. Relatively few Americans grow up with this kind of all-encompassing religious faith. Even fewer have known a life so completely bound by intricate rules and an extremely tight-knit community. But the central question she confronts—how to be true to herself within the context of other people’s expectations—is one almost everybody struggles with. And although Mirvis doesn’t gloss over the pain and disruption the divorce caused her children, it’s hard to disagree with her choice in favor of “living honestly and freely,” as she puts it, rather than let the kids grow up in a home filled with anger and resentment. The book seems briefly in danger of delivering a too-simple happy ending, but Mirvis is not one to take the easy way out. She finally leaves her own story in a moment of daring and confusion, suggesting that true happiness is complicated and always hard-won.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.

Tagged: Nonfiction, Tova Mirvis