Poet, novelist, and essayist Allen Tate (1899-1979) was one of twentieth-century America’s most important literary voices. Born in Kentucky and a graduate of Vanderbilt, Tate was a central figure in the circle of Nashville writers who came to be known as the Fugitives—and later the Southern Agrarians—a group which included John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren, Donald Davidson, and Merrill Moore. Tate was a true man of letters: he wrote biographies of Stonewall Jackson and Jefferson Davis, the well-regarded novel The Fathers, and several books of poetry and literary criticism. In 1943 he was named Poet Laureate of the United States.

Though in many ways a literary conservative, Tate struggled to reconcile the traditional culture he experienced as a Southerner with the realities of modern life, a tension that lies at the heart of his best-known poem, “Ode to the Confederate Dead.” He likewise incorporated modernist flourishes in his work even as he retained a commitment to classical form, a tendency that put him at odds with Ransom, his mentor, but helped him build a lasting friendship with T.S. Eliot.

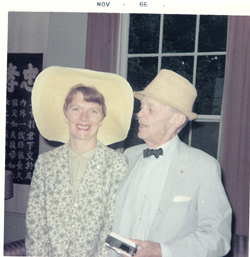

Tate taught at Sewanee, Princeton, Kenyon, and other schools before settling at the University of Minnesota. In 1966 he married Helen Heinz, who had been a student in one of his graduate courses, and the next year the couple moved, with their two sons, to Sewanee, where Tate taught until 1977, when illness forced him into retirement.

Tate taught at Sewanee, Princeton, Kenyon, and other schools before settling at the University of Minnesota. In 1966 he married Helen Heinz, who had been a student in one of his graduate courses, and the next year the couple moved, with their two sons, to Sewanee, where Tate taught until 1977, when illness forced him into retirement.

After her husband’s death in 1979, Helen Tate settled in Nashville, where she continues to work and volunteer. As Tate’s widow, she is one of the few living links to a critical moment in American literary history and a reminder of Nashville’s central role in the emergence of modern poetry. She recently spoke with Chapter 16 about her husband and his literary legacy.

Chapter 16: Talk about how you first met Mr. Tate.

Helen Tate: I was a graduate student at Minnesota, actually in nursing, but I had enough credits to work on a master’s in English as well. So I was in class with him.

Chapter 16: And why did you move back to Tennessee?

Tate: Allen knew he was going to retire, though he was still teaching full time at the time. We left for a semester while he was a visiting professor at UNC Greensboro, then he taught at Vandy for a semester, also as a visiting professor, after which he retired from Minnesota as an emeritus professor, and we moved to Sewanee. We left Minnesota with, I think, like some Southern writers do, a rather unique picture of the Old South, to find that really the Old South did not exist.

Chapter 16: At this point he had been outside the South for several decades, right? Did that inform his expectation of a return to the Old South?

I would say to him, “Allen, how do you expect people to understand this?” And he’d say, “I don’t write for those people.”

Tate: He was at Minnesota for fifteen years, and before that he was at Princeton. I think the South always has this romantic view of itself as the Old South, though that had pretty much disappeared. The population now is not Old South; it’s people who have moved here from the north and from other countries. That romantic view of the South as Gone with the Wind—which by the way he thought was an absolutely horrible book and did not refrain from expressing that [opinion]—did not exist, and I think Allen did not find it existing in the way he remembered.

Chapter 16: What was it like teaching and living at Sewanee?

Tate: He was there eight years, from 1969 to 1977, when he was pretty sick. It was very isolated, but we’d have visitors; the ones I remember most are [Robert Penn] Red Warren, who came to visit several times, and Peter Taylor, who would spend summers at Monteagle. We saw both Peter and Eleanor [Taylor]—by the way, Eleanor Taylor was a splendid poet in her own right. And people like Cleanth Brooks and Malcolm Cowley came to see us quite often. A lot of lit people stayed at our house, even though it was not huge, but there were very few places in Sewanee to house a guest. We went to Europe once or twice while in Sewanee; we saw T.S. Eliot’s wife. But soon Allen became so very sick. His doctors were at Vanderbilt, so we left there in 1977 and moved to a house in West Meade.

One time he was reading to a ladies’ group in Greensboro, and he read “Ode to the Confederate Dead.” At the end they all got up and clapped. He said, “No, please don’t clap for me.” And they said, “Mr. Tate, we’re clapping for the confederate dead.”

Chapter 16: In the second half of his career, he was well known as teacher, mentoring such young poets as Robert Lowell and John Berryman. What was he like in the classroom?

Tate: He was a splendid teacher. He had a way of drawing the class into the interpretation of poetry. He would give a lot of biographical background on a poet, often because it was someone he knew, and he was great at exploring different types of poetry—that’s why his classes were so popular. Not necessarily just for people who aspired to be writers, but people who just appreciated his delivery. But he did not give a lot of latitude to the class. I took a poetry class a few years ago, and the teacher let everyone give their own interpretation of each poem, some of which were so far-fetched. And yet the teacher would say, “Well that could be.” Allen would never tolerate that. If someone had a good, well-researched explanation, then he certainly would allow that, but he wouldn’t let them go off into deep ends.

Chapter 16: Did he ever reflect on his relationship with the Fugitive poets and the Agrarians? What did he think of that time?

Tate: He had a great reverence for what they, these young students, did in their meetings and how they encouraged the writings of one another and would get together and read one another’s compositions. I think on the whole he had great admiration for what they did at the time and that it really and truly put Vanderbilt on the map. He was definitely a spokesperson for that. In the 1920s the South was considered backwards; no legitimate writer came from the South. The South was just people sitting on front porches and telling stories.

Chapter 16: What was his relationship with Robert Penn Warren like?

Chapter 16: What was his relationship with Robert Penn Warren like?

Tate: They remained very close. He always said that Red Warren, and I can’t affirm this one hundred percent, sent him most of his poetry before [it was] published, for Allen to make comments. Allen felt he was sort of the last judgment. [Warren] came to visit us once in Sewanee; the boys were five and seven, and he came with army pocket knives which he gave to them. These little red army knives. The children were just mesmerized that he was giving them big-boy gifts.

Chapter 16: What was he like as a father?

Tate: People always said Allen was so sick in the end, so how could he be a good father? But the children [John and Ben] remember him so well. He played with the children all the time. Every spare minute he was with them, in the few years they had him. He spent so much more time with the children than other fathers do who work seven to seven o’clock at night. He was there any time he wasn’t teaching. John and he developed a huge and great admiration for trains. Every noon when the train came though Cowan [a town near Sewanee], they gave themselves twenty minutes, hopped in the car and went down to see it. John to this day has a great love of trains.

Chapter 16: Mr. Tate was a great teacher, but he was also known as a “poet’s poet.” Could you talk about that a bit?

Tate: All of his poetry, except for a few things at the very end, have all the classical references, both Greek and Latin. I would say to him, “Allen, how do you expect people to understand this?” And he’d say, “I don’t write for those people.” He wasn’t faulting you if you didn’t understand it, but if you didn’t, then his poetry wouldn’t mean as much. That was the way it was. One time he was reading to a ladies’ group in Greensboro, and he read “Ode to the Confederate Dead.” At the end they all got up and clapped. He said, “No, please don’t clap for me.” And they said, “Mr. Tate, we’re clapping for the confederate dead.”

What we perceive as obscure was to him like reading a simple little poem. The Latin and the Greek—who doesn’t understand Latin and Greek? It was part of his education.

Chapter 16: That’s hilarious, because the poem’s not really about the confederate dead at all. Yet as his most famous poem, it must have come under that kind of misinterpretation all the time. Did that bother him?

Tate: I don’t think so. I think he was amused more than anything else. It didn’t bother him, even though he was so familiar with writing at that level of complexity. It wasn’t like he was creating something obscure. What we perceive as obscure was to him like reading a simple little poem. The Latin and the Greek—who doesn’t understand Latin and Greek? It was part of his education. That’s not contemporary education, let’s face it. So for people reading his poems now, it’s like reading a foreign language.

Chapter 16: He must have noticed the decline of educational standards later in his life. What did he think about that?

Tate: For him it was an era that had sort of ended, and another one was coming, and you don’t have much to say about how it will evolve. It’s just sort of a reconciliation to it.

Chapter 16: Sort of the same way he saw the changing South?

Chapter 16: Sort of the same way he saw the changing South?

Tate: He felt you couldn’t be a reactionary about it. He was a great Civil War scholar, but he really felt too that the interest in Civil War battlefields would disappear at some point, that our grandchildren would not know what the Civil War meant. He had a resolve that it’s going to change and you have to sit here and cling to what you remember and what you think is important to you, and at some point it will be a little dandelion puff that will blow away.

Chapter 16: What did Mr. Tate think about the social and cultural changes of the 1960s?

Tate: Robert Bly [the poet] was not on his list of favorite people. [Artist] Robert Indiana was not on his list of favorite people. He wrote something in the local paper about Robert Indiana once and got many caustic responses. I think there was a certain tolerance toward Andy Warhol. But as to some of the modern writers, confessional writers—he took very dim views of people who felt like they needed to confess everything in poetry and get very personal. That strictly confessional poetry was in at the time, and still is.

Chapter 16: Did he have a particular set of reasons for his dislike of modern art?

… You have to sit here and cling to what you remember and what you think is important to you, and at some point it will be a little dandelion puff that will blow away.

Tate: I think he thought it was more illustrations than anything else.

Chapter 16: What was his relationship with T.S. Eliot like?

Tate: Eliot came to Minneapolis once and spoke at the outdoor stadium; there was a huge big crowd. He was a very humble man, with beautifully spoken English. Eliot was pretty much a mentor to Allen. If anyone stood out in Allen’s background whom he admired most, it would be T.S. Eliot.

Chapter 16: He was America’s second poet laureate, but you’ve said you think Mr. Tate will be better remembered as an essayist. Why?

Tate: Except in small classes on Southern literature, “Ode to the Confederate Dead” is his only poem that’s still taught. And I would be surprised if there are many English teachers, except in the South, who have him on their reading list at all. I think that era of poetry is a forgotten era, and of course there’s the complexity of his poetry. But Jonathan Yardley of The Washington Post has argued that Allen’s essays are extremely insightful, that he really caught the essence of the writer. I think his essay on Emily Dickinson is really first-rate. I think for teachers in this era that are talking about those writers, I bet you would hear them reference the materials, quote from those essays.

Chapter 16: What was your relationship with him like? Did you discuss his work with him very much?

Chapter 16: What was your relationship with him like? Did you discuss his work with him very much?

Tate: I would do a lot of his correspondence, though later he had a kid from Sewanee come over and do that. We talked a lot about what happened to the Old South. I felt like the things he would tell me about the Old South I never saw—Allen remembered the South as being marked by a generational tenacity, in which generations passed on things to generations. The old agrarian thing about respect toward the land, that’s gone entirely now.

Chapter 16: Was Mr. Tate disappointed by this loss?

Tate: I think it was more resignation than anything. He knew that the agrarian past, that life, was going to disappear with commercialization and mechanization. He tried to have a little garden while we were in Sewanee. It didn’t do very well. He tried to grow corn, but it didn’t want to grow.

Tagged: Poetry