In 2009, on New Year’s Day, I got fired from my job as the book-page editor of the Nashville Scene. I was standing in line at Target when the paper’s editor-in-chief called my cell and got right to the point: “We’re canceling the book section,” he said. “I’m sorry, but I have to let you go.”

“OK,” I said.

“Happy New Year,” he said.

In the face of disappointment I’m normally a full-throated keener, so if I took this bad news better than I typically accept setbacks, it’s only because this bit of bad news didn’t come out of the blue. In fact, I’d been expecting the call for more than two years, ever since the Scene’s parent company at the time was bought by a rival syndicate—a company that had never covered books. When your job is to edit book reviews at a newspaper owned by a chain that doesn’t cover books, you don’t need to be John Grisham to know how the plot ends.

When I tell the story of how I came to my job as the editor of a daily publication that covers the literary life of Tennessee, I always start with the story of getting fired from the Nashville Scene on New Year’s Day in 2009. It’s a story with a clean narrative line, a story in which the forces of literary culture were defeated by the forces of corporate darkness. Then, I say, a hero arrived.

When I tell the story of how I came to my job as the editor of a daily publication that covers the literary life of Tennessee, I always start with the story of getting fired from the Nashville Scene on New Year’s Day in 2009. It’s a story with a clean narrative line, a story in which the forces of literary culture were defeated by the forces of corporate darkness. Then, I say, a hero arrived.

This is the tale of how Tennessee literature was saved from a fate closely resembling oblivion by an unlikely hero: the United States government. Specifically, it was saved by the tiny portion of the U.S. federal budget allocated to the National Endowment for the Humanities. More specifically, by the even tinier part of the federal budget that the NEH budget disburses to Humanities Tennessee, an independent affiliate of the national agency. The knight in shining armor who swooped in to save literature, it turns out, was Uncle Sam.

Earlier this year, when the White House announced a proposal to eliminate all funding for the cultural agencies—the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting—a great hue and cry rose up from people who understand what these programs do for the country. For poets and writers, though, the despair and disbelief seemed to focus almost exclusively on how the elimination of the cultural agencies would affect public television, public radio, and the arts. The “humanities” include a wide range of disciplines—history, philosophy, linguistics, archaeology, religion, ethics, etc.—and in that context what the NEH does to support literature isn’t always very clear in the public imagination.

But in Tennessee we can offer one perfectly transparent story of how writers are profoundly affected by federal funds disbursed through the NEH. It starts not with the cancellation of the Nashville Scene’s book page, but with the Great Recession. If you’re the editor of a newspaper whose advertising sales have dried up, you have no choice but to downsize and hope you can survive long enough with a skeletal staff for the economy to rebound.

But in Tennessee we can offer one perfectly transparent story of how writers are profoundly affected by federal funds disbursed through the NEH. It starts not with the cancellation of the Nashville Scene’s book page, but with the Great Recession. If you’re the editor of a newspaper whose advertising sales have dried up, you have no choice but to downsize and hope you can survive long enough with a skeletal staff for the economy to rebound.

I can guess what you’re thinking: it’s not like the book section of one newspaper in one town in one state of this vast country makes much of a difference in whether literature survives. This is the twenty-first century. If you’re looking for a new book to read, you go to Amazon, or Goodreads, or social media. Newspapers are so twentieth century.

Well, yes and no.

People outside the publishing world tend to assume that a book’s failure or success depends entirely on whether that book is any good. But people inside publishing understand that the very best book will sink like a stone to the bottom of the sea if readers don’t know it exists. And if you’re a debut author starting from zero—zero marketing budget, zero name recognition, zero famous writer friends—an online bookseller will not save you. Go ahead and upload your novel to Amazon, and let’s see how long it takes your friends to find it on their own. Don’t expect your mother to find it at all.

If you’re a debut author starting from zero, one thing you can do is give readings in ten or twelve independent bookstores around the country and hope those readings inspire the local newspapers to give your book some ink. Especially for authors who are just starting out—or whose work is difficult or challenging or written for a niche audience—local bookstores and local newspapers can mean the difference between respectable sales and failure. An enthusiastic bookseller will push a good book into the hands of readers long after the author’s appearance is over, and a good newspaper review makes for a link even your mother can find.

If you’re a debut author starting from zero, one thing you can do is give readings in ten or twelve independent bookstores around the country and hope those readings inspire the local newspapers to give your book some ink. Especially for authors who are just starting out—or whose work is difficult or challenging or written for a niche audience—local bookstores and local newspapers can mean the difference between respectable sales and failure. An enthusiastic bookseller will push a good book into the hands of readers long after the author’s appearance is over, and a good newspaper review makes for a link even your mother can find.

But that do-it-yourself marketing strategy wasn’t an option in January of 2009. By the time the Nashville Scene shut down its book page, the city’s daily paper, The Tennessean, had already stopped running book reviews. Across Tennessee, newspapers had fired their literary editors and shuttered their book pages. If a newspaper continued to cover books at all, it relied on short pieces taken from a wire service—reviews of books by established authors who had nothing to do with Tennessee.

If you were a Tennessee writer with a new book coming out at the beginning of the Great Recession, your only hope was the remote chance of a national review. And even in the best of economic times, that hope is a long shot: of the 750-1,000 books delivered to The New York Times Book Review every week, only twenty to thirty are chosen for coverage.

Besides, it wasn’t just local newspapers who were being hit hard by the Great Recession. The national newspapers were contracting, too. The Washington Post shut down its freestanding book supplement and folded book coverage—much less book coverage—into its Sunday features section. Same thing happened at the Los Angeles Times. Hoping for a national review in 2009 was like hoping to wake up covered in fairy dust.

Besides, it wasn’t just local newspapers who were being hit hard by the Great Recession. The national newspapers were contracting, too. The Washington Post shut down its freestanding book supplement and folded book coverage—much less book coverage—into its Sunday features section. Same thing happened at the Los Angeles Times. Hoping for a national review in 2009 was like hoping to wake up covered in fairy dust.

Here’s an example: Clay Risen’s first book, A Nation on Fire, was published at the beginning of 2009. By the time the book appeared, Risen—who now serves as deputy editor of op-eds at The New York Times—had built a national reputation as a journalist, writing for prestigious publications like The Atlantic and The New Republic. When his first book was published, he had already racked up more than two dozen freelance bylines in The New York Times, but did the Times review his first book? It did not.

Clay Risen is a Nashville native. He cut his writing teeth as a freelancer at the Nashville Scene. His book—about the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King—should have been of particular interest to Tennesseans. But by the time A Nation on Fire was released, Tennessee newspapers were no longer covering local books, and local readers had no way of finding out his book even existed. Neither the Nashville Scene nor The Tennessean, the Nashville daily, reviewed it. Even The Commercial Appeal—the daily paper in Memphis, where Martin Luther King was actually assassinated—skipped it. I recently asked Risen about that time. “It felt apocalyptic,” he said.

Meanwhile, that other pillar of support for local writers, the community bookstore, was also in trouble. If the wretched economy had dealt local newspapers a nearly mortal blow, the hit to bookstores was even worse. Just as the Internet had cut into newspaper profits by siphoning off advertising revenue, it had cut into bookstore profits by offering cheaper books online. Barely more than a year into the recession, scores of bookstores—from tiny independents to giant chains—had gone bankrupt, and Nashville didn’t have a single reporting bookstore left.

Meanwhile, that other pillar of support for local writers, the community bookstore, was also in trouble. If the wretched economy had dealt local newspapers a nearly mortal blow, the hit to bookstores was even worse. Just as the Internet had cut into newspaper profits by siphoning off advertising revenue, it had cut into bookstore profits by offering cheaper books online. Barely more than a year into the recession, scores of bookstores—from tiny independents to giant chains—had gone bankrupt, and Nashville didn’t have a single reporting bookstore left.

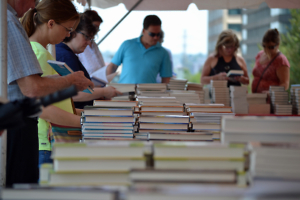

Using a mixture of private donations and federal funds disbursed by the NEH, Humanities Tennessee was already an old hand at cultivating the literary life of this state. Every October, Humanities Tennessee brings 250-plus authors to Nashville for the Southern Festival of Books. Every summer, Humanities Tennessee sponsors two different week-long writing workshops for Tennessee teenagers. Each year Humanities Tennessee sends writers into impoverished public schools across the state to talk with students who have never met an author in their lives. And then it gives every kid in the school a copy of that author’s book for free.

With bookstores closing and newspapers killing their book pages, the staff at Humanities Tennessee had a brainstorm. What about starting a daily online publication to highlight new books by Tennessee authors in the same way that bookstore shelves and local newspapers once had? A Tennessee-based New York Times Book Review for books The New York Times Book Review wouldn’t touch?

In the context of the budget of the United States, the budget of the National Endowment for the Humanities is infinitesimal. In 2016 it represented 0.003 percent of the federal budget—that’s one three-hundred-thousandth of the funds it takes to run this country. And yet the Endowment’s budget is always tight; NEH funding was already taking hit after hit even before the recession. (Like all state affiliates of the NEH, Humanities Tennessee works constantly to secure private and corporate gifts to support programs they would not be able to offer based only on federal grants.)

In the context of the budget of the United States, the budget of the National Endowment for the Humanities is infinitesimal. In 2016 it represented 0.003 percent of the federal budget—that’s one three-hundred-thousandth of the funds it takes to run this country. And yet the Endowment’s budget is always tight; NEH funding was already taking hit after hit even before the recession. (Like all state affiliates of the NEH, Humanities Tennessee works constantly to secure private and corporate gifts to support programs they would not be able to offer based only on federal grants.)

The publication Humanities Tennessee dreamed up is called Chapter 16: A Community of Tennessee Writers, Readers & Passersby. (The name is a reference to Tennessee’s history as the sixteenth state to join the union.) They built the site in-house by reading a book called Drupal for Dummies, and they hired me to run it. The reviewers who’d lost their gigs when newspapers killed their book pages got back to reading and writing, and in October 2009 on the first day of the Southern Festival of Books—in what later turned out to be the very worst quarter of the Great Recession—Chapter 16 went live for the first time.

The site offers book reviews and author interviews; excerpts from forthcoming books; original poems and essays; features on literary events around the state; and news about Tennessee writers. And this content is paid for out of a significant freelance budget—at Chapter 16 we hire professional writers, and we pay them for their work. And even during the deepest trough of the recession, if you were a Tennessee author with a new book, or an author who once lived in the state, or an out-of-state author giving a reading here, you could be sure that at least one corner of the Internet was paying attention.

Within a few weeks of the site’s launch, that little corner of the Internet made it into print, as well, when Humanities Tennessee began offering Chapter 16’s reviews and interviews for reprint, free of charge. We knew that newspapers hadn’t stopped covering books because they suddenly stopped caring about books. Newspapers stopped covering books because they could no longer afford to cover books. Today, through this unusual public-private partnership, you can find Chapter 16 content in some of the biggest dailies in the state (the Knoxville News Sentinel and the Memphis Commercial Appeal) and in one of the smallest (the Norris Bulletin). Fittingly, the very first newspaper to accept our offer was the Nashville Scene.

Book news rarely goes viral in the age of BuzzFeed headlines, but Chapter 16 reaches a respectable number of readers. Thanks to our social-media presence and a free weekly newsletter, as well as to our newspaper partnerships, we count nearly half a million readers on a good week. And that’s enough to get the notice of New York.

When publishers know their authors will be covered in the local media, they’re much more likely to send those authors to Tennessee for a book signing. Even during the darkest days of 2011, when Nashville didn’t have a single bookstore reporting to the bestseller lists, writers of national renown were giving readings here through a partnership between Humanities Tennessee, the Nashville Public Library, and the Nashville Public Library Foundation. And because the Scene—using Chapter 16 copy—was helping to get the word out, crowds were spilling out of the auditorium and into the halls.

No one at Humanities Tennessee would ever claim that Chapter 16 saved literature in this state. Ann Patchett and Karen Hayes saved Tennessee literature when they opened Parnassus Books in Nashville. Flossie McNabb and Melinda Meador saved Tennessee literature when they opened Union Ave. Books in Knoxville. Susannah Felts and Katie McDougall of The Porch Writers’ Collective saved Tennessee literature by creating a community for serious aspiring writers. Elizabeth Nelson and Carmen Toussaint saved Tennessee literature when they opened Rivendell Writers’ Colony to offer affordable literary retreats. The list goes on and on.

But before any of that happened, the staff at Humanities Tennessee came up with an innovative plan to fill the gap. Wisely marshalling grants provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, they stepped in where the private sector was failing literature—where publishers were failing, and bookstores were failing, and newspapers were failing—and came up with a way to help writers find readers, and readers find books they’ll love. And as long as the National Endowment for the Humanities survives, we’ll be here to keep supporting the vibrant, ever-expanding community of Tennessee readers and writers, and to welcome all book-loving passersby.

Margaret Renkl is the editor of Chapter 16 and a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times. She lives in Nashville.

Tagged: Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry