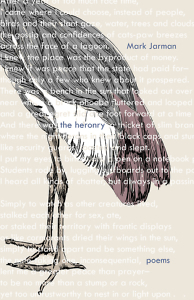

The stunning title poem of Mark Jarman’s eleventh collection, The Heronry, could serve as a précis for his entire body of work. His core themes of spirituality and nature, his fondness for abiding in the mystery of ordinary experience, and his quietly fierce moral sense are all there, conveyed in language that is at once simple and cerebral. When Jarman describes birdwatching as an opportunity “simply to stand apart and be something else, / the note-taking one, inconsequential,” he is also talking about the impulse that drives his own vocation as a poet.

That vaguely self-deprecating word—“inconsequential”—is revealing. To the extent that any poet is really able to choose an authentic voice, the characteristic modesty of Jarman’s style seems cultivated—not as an affectation or an aesthetic stance, but as a strategy for sidling up on elusive, fleeting states of mind and exploring their reconciliation with the material weight of everyday experience. This quest is the primary work of his poetry, and it’s as difficult a task as stalking the uncooperative birds of “The Heronry”:

I tried to observe behavior I could note in my book,

though every time I thought I’d captured a stride or a wing beat,

it altered, or the hunter missed.

In “The Northern Lights,” Jarman grapples directly with the difficulty of reconciling what is ineffable and enduring with the reality of human limitations. The literal lights—“a white electric squall in half the sky”—become, over the course of the poem, “the background music of creation,” a manifestation of God, but the real subject here is mortal love, as personified in his parents. Nestled within the poem is a warning not to confuse the two planes of being:

Don’t ever think of human beings you love

and need as like those shifting shimmerings,

no matter how liquescent memorable enduring

against the immortal darkness of the sky.

The sixty poems in the collection are arranged in three groups—“The Heronry,” which includes the title poem and others with strong natural imagery; a set called “Believers, Unbelievers,” made up largely of character poems; and a sort of diverse catchall group called “Another Field.” The character poems are brilliant short narratives that sometimes have a gentle sense of humor but more often lean toward heartbreak. “Reverend ‘Rev’ Rebenek” is about a sweet-souled, washed-up preacher for whom failure “swung past his face like leaves in fall.” “Betsy Moore” depicts the sad plight of a church elder’s wife, who takes a call from her husband as he lies in a motel bed with his lover. The husband is “as moral as a contract,” but Betsy is his opposite number, a woman of great righteousness who, every Christmas, “poured the gifts of liquor / from his associates down the kitchen sink, every bottle.” The poem challenges our natural sympathies without making any attempt to subvert them.

Surely the most surprising character to pop up in The Heronry is George W. Bush. The subject here is Bush’s well-known conversion experience and his denial of guilt for the suffering of America’s Iraq War veterans. Jarman’s tone here is subtly bitter, sardonic. “How much is anyone whose heart speaks for him / responsible for what it has told him?” he writes, and though the poem seems to be genuinely asking the question, there’s no doubt that the poet has made a judgment, at least about Bush’s escape from earthly consequences for his actions.

Surely the most surprising character to pop up in The Heronry is George W. Bush. The subject here is Bush’s well-known conversion experience and his denial of guilt for the suffering of America’s Iraq War veterans. Jarman’s tone here is subtly bitter, sardonic. “How much is anyone whose heart speaks for him / responsible for what it has told him?” he writes, and though the poem seems to be genuinely asking the question, there’s no doubt that the poet has made a judgment, at least about Bush’s escape from earthly consequences for his actions.

Perhaps it’s a minor bit of literary justice that “George W. Bush” immediately follows “Bad Girl Singing,” which depicts a dislikable, ill-behaved young woman who stymies all disapproval with the ethereal beauty of her voice. “She sang her rejection of our rejection,” Jarman writes, and the miracle of her gift makes Bush’s moral feebleness, by contrast, seem all the more repugnant.

Although Jarman writes powerfully about great spiritual questions, some of his most moving poems stay rooted entirely in a felt moment or a humble image. Poems here such as “Catch and Release,” in which a scientist’s azalea plant serves as a memento of youth, and “Bat,” which simply reflects on the experience of watching the animal, create a wealth of feeling out of very little. And no poem here is more memorable than “Mothering Sunday,” in which a woman brings her adult, homeless son to a church service, only to have him flee when his moment comes to honor her. The last line—“He’d been her flower”—is as poignant as any in the collection. The witness in this poem seems to be Jarman himself, that same modest poet from “The Heronry,” taking notes and doing his best to capture the beat of a wing or heart.

[To read an excerpt from The Heronry, click here.]

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.

Tagged: Mark Jarman, Poetry