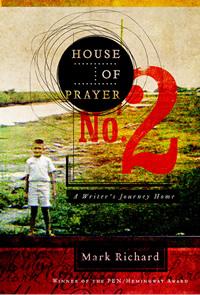

Not all fairytale plots are set into motion by an act of villainy. Sometimes, according to Morphology of the Folktale by Vladimir Propp, a hero is spurred to action when faced with an “inefficiency or lack.” In Mark Richard’s crackling memoir, this “lack” is a childhood disability that made it difficult for him to walk and led others to suspect he was cognitively impaired. In fact, Richard could read aloud from a college chemistry book at age six but was classified by his school as “slow” because he could not color the state bird correctly. His own physical challenges and the assumptions they inspired in others informed Richard’s sensibilities, set the stage for his brilliant memoir, House of Prayer No. 2, and ultimately explains why he is now one of the South’s finest writers.

When House of Prayer No. 2 was first published last year, reviewers described the book as “absorbing” (The New York Times), “stylistically audacious” (The New Yorker), “gorgeous” (The Christian Science Monitor), “extraordinary” (Garden & Gun), “fascinating” (Publishers Weekly), and “intoxicating” (Southern Literary Review). Like virtually all books written in the second person, House of Prayer No. 2 also drew the inevitable comparisons to Jay McInerney’s 1984 novel Bright Lights, Big City, but a more apt predecessor might be the Old Testament. Richard’s prose style carries an undeniably Biblical musicality, and many of his stories are pithy, often told with minimal explanation but to tremendous effect. The final third of the memoir, which describes Richard’s own awakening, is also explicitly religious.

This is not a stereotypical redemption narrative, however, and the book never shies from material that occasionally qualifies as dark, even unsettling. “Say you have a ‘special child,’” the book begins. After describing for several pages the child’s physical disabilities, wild behavior that includes but is not limited to biting, and a dysfunctional family life in 1960s rural Virginia, Richard shifts to the personal: “Say you are the special child.”

This is not a stereotypical redemption narrative, however, and the book never shies from material that occasionally qualifies as dark, even unsettling. “Say you have a ‘special child,’” the book begins. After describing for several pages the child’s physical disabilities, wild behavior that includes but is not limited to biting, and a dysfunctional family life in 1960s rural Virginia, Richard shifts to the personal: “Say you are the special child.”

Named for the church Richard was later instrumental in helping to rebuild, House of Prayer No. 2 depicts one man’s lifelong search for solid footing, physical and spiritual. In between a childhood spent on crutches and an adult call to religion, Richard spent decades freewheeling around the country, raising hell and writing fiction. “The first time you are arrested, it is for assaulting a police officer,” he writes, describing the time, as a teenager, when he used a water pistol to shoot an officer in the face. He cites specific examples from his derelict early thirties of casual relationships with women, altercations in bars. But he also understands, perhaps better than any male writer mining his childhood for material since Harry Crews, that his experiences of alienation and misery have endowed him with compassion and, by extension, a rich life. The darkness is part of what makes illumination possible.

This memoir is Richard’s first work of nonfiction: he’s also the author of a bestselling novel, Fishboy, as well as two stellar collections of short stories, one of which, The Ice at the Bottom of the World, won a 1990 PEN/Hemingway Award. He has written screenplays and scripts for a number of television shows. Whatever the form, every event and conversation he describes positively glimmers with life. In describing a moment that occurred while visiting the woman who would later become his wife, he writes, “One morning you are lying on the extra bed on the sunporch, where she’s been letting you stay, and you can see her through the open door in her office wearing a pair of her father’s old pajamas, with her feet up, drinking coffee and smoking a cigarette, reading the sports page, and you think, Her.”

This memoir is Richard’s first work of nonfiction: he’s also the author of a bestselling novel, Fishboy, as well as two stellar collections of short stories, one of which, The Ice at the Bottom of the World, won a 1990 PEN/Hemingway Award. He has written screenplays and scripts for a number of television shows. Whatever the form, every event and conversation he describes positively glimmers with life. In describing a moment that occurred while visiting the woman who would later become his wife, he writes, “One morning you are lying on the extra bed on the sunporch, where she’s been letting you stay, and you can see her through the open door in her office wearing a pair of her father’s old pajamas, with her feet up, drinking coffee and smoking a cigarette, reading the sports page, and you think, Her.”

House of Prayer No. 2 connects the gorgeously written (if harrowing) vignettes from Richard’s childhood to the man that he grows up to be, but it simultaneously rejects the power of those experiences to dictate Richard’s identity and potential. Aside from the literal story of his come-to-Jesus awakening, this memoir is, at its heart, a book of redemption: unpacking the past, telling the truth, and, finally, choosing his own path. It’s an enormous, and enormously affecting, tale of personal reconciliation.

Mark Richard will discuss House of Prayer No. 2 at Lipscomb University in Nashville on March 29 at 7:30 p.m. at the Ezell Center. The lecture is free and open to the public. Click here for event details.

Tagged: Nonfiction