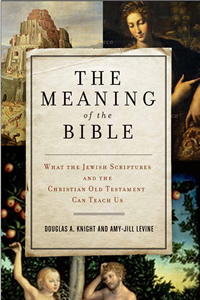

“I don’t believe people are looking for the meaning of life as much as they are looking for the experience of being alive,” Joseph Campbell once said. “Being alive is the meaning.” Two Vanderbilt professors, Douglas Knight and Amy-Jill Levine, have made careers out of investigating the history, culture, and legacy of texts to which people have turned in their search for meaning. In their new introduction to the Jewish Scriptures and Christian Old Testament, boldly titled The Meaning of the Bible, Knight and Levine ask us to consider how the Bible itself is alive in the imaginations, interpretations, and public discourse of those who have lived in the echo of its words for millennia.

Through decades of teaching and engaging numerous conversation partners, Knight and Levine tackle what they call “the knottier problems the biblical texts pose.” Informed by the diversity of their own scholarly interests and personal religious commitments, this introduction to the Hebrew Bible, subtitled “What the Jewish Scriptures and Christian Old Testament Can Teach Us,” asks both devout and dismissive readers to turn again to the texts, themes, and cultural legacy of this work to “find new appreciation, ask new questions, and raise new interpretations.”

Through chapters exploring the interplay of themes like Law and Justice, Chaos and Creation, Self and Other, Politics and Economy, Wisdom and Theodicy, Levine and Knight suggest that reading the Bible is not so much about the meanings we are searching for but about how, when, and why we have been on the search at all. The Meaning of the Bible concludes, “With this diversity of approaches and responses, it is clear that the Bible is not a book of answers. It may be, however, a book that helps its readers ask the right questions, and then provides materials that can spark diverse answers.”

2011 was a good publication year for both Amy-Jill Levine and Douglas A. Knight: in addition to The Meaning of the Bible, Levine also edited The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford University Press), and Knight also wrote Law, Power, and Justice in Ancient Israel (Westminster John Knox Press). They recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email about The Meaning of the Bible itself and their own collaborative work:

2011 was a good publication year for both Amy-Jill Levine and Douglas A. Knight: in addition to The Meaning of the Bible, Levine also edited The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford University Press), and Knight also wrote Law, Power, and Justice in Ancient Israel (Westminster John Knox Press). They recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email about The Meaning of the Bible itself and their own collaborative work:

Chapter 16: You’ve collaborated on an ambitious project and given it a bold title. Is it possible to summarize what meaning(s) you hope readers discover?

Levine and Knight: We hope readers will discover that the Bible speaks with a symphony of voices—with different perspectives offered to different readers in different locations at different times. Further, we hope readers will appreciate the diverse ways that the text has been interpreted over the centuries. By providing readers a sense of how the text came to be composed, of what it would have meant to its original audiences, and of how it both shaped and was shaped by its culture, we seek to enrich the faith of those who claim the Bible as sacred scripture, to inform all readers of the sweep of biblical history and the majesty of biblical literature, and to challenge those who find only one voice, or one message, to look again.

Chapter 16: What is the greatest misconception about the Bible that you hope readers will reconsider?

Levine and Knight: The Bible frequently functions in moral and political contexts today as a guide for public policy, and in the process it is too often used as a bludgeon to bash those who hold opposite points of view. The search for relevance is good, but dogmatic or inflexible postures can be harmful, let alone untrue to the diverse messages in the text. Instead of viewing the Bible as a book of answers, we hope readers will see the text as helping us to ask the right questions: of human responsibilities, of how to treat the natural world, of how to react to despair, of how to understand ourselves and our neighbors.

Chapter 16: For the religious, the very word Bible carries a connotation of sacredness. What meaning-making does your book and its subject hold for those who aren’t religious?

Levine and Knight: The Bible is the basis of much of art, literature, theatre, and music, and it is also a source of much of today’s moral concerns. It is not simply a text about specific religious beliefs and practices; it is a text with much to teach us about history, narrative, community, psychology, politics, economics, and suffering.

Levine and Knight: The Bible is the basis of much of art, literature, theatre, and music, and it is also a source of much of today’s moral concerns. It is not simply a text about specific religious beliefs and practices; it is a text with much to teach us about history, narrative, community, psychology, politics, economics, and suffering.

Chapter 16: How would you describe the nature of your collaboration? Were there points of contention—or points of connection—that you didn’t anticipate in embarking on this project?

Levine and Knight: We both teach this material, and we easily agreed on the major themes to be addressed. Happily, our interests complement each other: Doug is an expert on history, law, and prophetic literature; A.-J., a specialist in narrative, apocalyptic, and gender studies. Doug works on the centuries from the early Iron Age to the Persian period; A.-J. concentrates primarily on the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. Doug deals with ancient Near Eastern literature and religion; A.-J. focuses on early Jewish movements and literature, especially in relation to their Greek counterparts. When we sat down to write this book, we each drafted seven chapters and then shared our work with the other.

Chapter 16: For an introduction to the Bible, your organization of this book is innovative. Why did you choose the thematic approach?

Levine and Knight: To approach the text in terms of chronology does a disservice to the text: Genesis 1, the story of creation “in the beginning,” was probably written later than Genesis 2-3, the story of Adam and Eve. The book of Ruth is set in the period of the Judges, but it most likely stems from the time following the Babylonian exile, about a millennium later. The book-by-book approach creates problems not only in dating, but also in the question of canon: The books in the (Christian) Old Testament appear in different order than those in the (Jewish) Tanakh; even within the Christian traditions the Protestant order and content vary from the Roman Catholic, and both from the Eastern Orthodox. The thematic approach provides the best way to show the diversity of biblical views. Finally, this organization allows any reader easily to see what the Bible says about the subjects of concern today: sex, politics, economics, personal and ethnic identity, creation, God, and so on.

Chapter 16: In your chapter on the exodus, you write: “A text can be historical in more ways than one.” With such a muddy relationship between fact and fiction in Biblical events, what in your view makes these stories authoritative enough to organize communal lives for generations?

Levine and Knight: First, a story does not need to be historically true in order to impact a community. The famous “Parable of the Good Samaritan” does not record an actual event, but it speaks a true message. Second, the Biblical material does not come to us without interpretation: for millennia (the term is not exaggerated) Jews and Christians have, in each generation, explained how they read the text, with each era, each location, and each person finding new meaning. Thus the Bible remains a living document. And third, each group and each individual decides on the authority of the text. The Bible carries enormous weight by virtue of its impact on many millions over these two millennia, but it is still a matter for each person and each community to decide on the nature and extent of its authority for them.

Tagged: Nonfiction