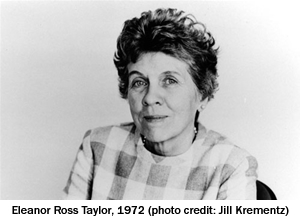

Born in 1920 on a North Carolina farm, during a time and in a place not particularly noted for encouraging the literary aspirations of young women, Eleanor Ross Taylor nevertheless grew up in a family of writers. (Her late brothers, James and Fred Ross, were novelists; her sister, Jean Ross Justice, is a fiction writer still.) While she was only a child, Taylor’s poems were published in state newspapers, including the Charlotte Observer. As a student at the Women’s College of the University of North Carolina (now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro), she was taught by the Fugitive poet Allen Tate and his first wife, Caroline Gordon. A scholarship to Vanderbilt University in Nashville landed her in the classroom of Donald Davidson.

Later, while visiting Tate and Gordon in Monteagle, Tennessee (where they were sharing a cottage with Robert Lowell and Jean Stafford), Eleanor Ross met Peter Taylor. Peter went on to become the much-decorated short-story master and novelist whom Jonathan Yardley, writing in The Washington Post in 1993, called “the best writer we have.” Eleanor went on to become his wife. “My husband’s career really came first,” she explained in a 2002 interview in the literary journal Blackbird.

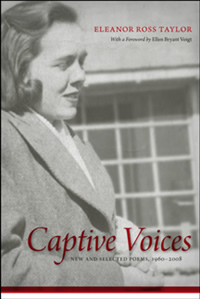

Even as her husband was becoming the literary lion of his generation, Eleanor Ross Taylor was quietly writing and publishing poems of her own, small gems of understatement and fearless clarity often compared to the works of Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth Bishop. Her first collection, Wilderness of Ladies, appeared in 1960 and was followed—at the rate of about one book per decade—by five others. In her late sixties, she began to win awards—from the Poetry Society of America and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among others. Lyric poetry is often regarded as a young person’s art, but by the time Peter died in 1994, Eleanor was in the midst of a remarkable late flowering. In 2009, she was elected to The Fellowship of Southern Writers, and her final book, Captive Voices, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry. In 2010, in her ninetieth year, Taylor won both the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Book Award and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize—which carries a stipend of $100,000—bestowed by The Poetry Foundation to honor “a living U.S. poet whose lifetime accomplishments warrant extraordinary recognition.”

Even as her husband was becoming the literary lion of his generation, Eleanor Ross Taylor was quietly writing and publishing poems of her own, small gems of understatement and fearless clarity often compared to the works of Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth Bishop. Her first collection, Wilderness of Ladies, appeared in 1960 and was followed—at the rate of about one book per decade—by five others. In her late sixties, she began to win awards—from the Poetry Society of America and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among others. Lyric poetry is often regarded as a young person’s art, but by the time Peter died in 1994, Eleanor was in the midst of a remarkable late flowering. In 2009, she was elected to The Fellowship of Southern Writers, and her final book, Captive Voices, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry. In 2010, in her ninetieth year, Taylor won both the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Book Award and the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize—which carries a stipend of $100,000—bestowed by The Poetry Foundation to honor “a living U.S. poet whose lifetime accomplishments warrant extraordinary recognition.”

Taylor spent her lifetime writing poems that, as Adrienne Rich once put it, “speak of the underground life of women, the Southern white Protestant woman in particular, the woman-writer, the woman in the family, coping, hoarding, preserving, observing, keeping up appearances, seeing through the myths and hypocrisies, nursing the sick, conspiring with sister-women, possessed of a will to survive and to see others survive.” Many years later, in the final lines of “Advice to a Young Writer,” Taylor articulates the quiet conviction behind all six of her own collections:

Taylor spent her lifetime writing poems that, as Adrienne Rich once put it, “speak of the underground life of women, the Southern white Protestant woman in particular, the woman-writer, the woman in the family, coping, hoarding, preserving, observing, keeping up appearances, seeing through the myths and hypocrisies, nursing the sick, conspiring with sister-women, possessed of a will to survive and to see others survive.” Many years later, in the final lines of “Advice to a Young Writer,” Taylor articulates the quiet conviction behind all six of her own collections:

Dear friends consign you

To sanatorium, prison, and the pall.

No, keep your chair,

Tuck your wits in,

Say finally

I did outdure them all

In honor of the achievements of Eleanor Ross Taylor, and to mark her passing last Friday, Chapter 16 contacted poets and novelists around the country to ask for their impressions of a writer who spent much of her literary life in the shadow of her husband, but who quietly continued her own work with passion and dedication during their fifty-one years together—and for more than a decade beyond his death. What emerges is a collaborative portrait of a woman who was quiet, modest, and gentle but whose poems were uncompromising, sharp, and (in a word that comes up again and again) fierce:

“Far more than a reclusive lady of genteel manners, Eleanor Ross Taylor was the most important Southern woman poet of the mid-twentieth century. Her first book came out in 1960, when she was forty years old. Her work was complex, and one could even say experimental, creating a highly individual but completely recognizable experience of women in the South, of the South—voices that had been absent from our poetry. She was fierce, strong, retiring, and wonderful.” ~Poet Betty Adcock, author, most recently, of Slantwise

“She was a lovely soft-spoken brilliant presence who knew how to make you feel as though she was attending to no one else but you, no matter how many people were in the room and no matter how many people she spoke to, all of whom got that same feeling. She attended, beautifully, and her work shows it.” ~Richard Bausch, creative-writing professor at the University of Memphis and author, most recently, of Something is Out There: Stories

“She was a lovely soft-spoken brilliant presence who knew how to make you feel as though she was attending to no one else but you, no matter how many people were in the room and no matter how many people she spoke to, all of whom got that same feeling. She attended, beautifully, and her work shows it.” ~Richard Bausch, creative-writing professor at the University of Memphis and author, most recently, of Something is Out There: Stories

“In some ways, Mrs. Taylor’s entire canon can be summed up by the vivid, singular, and, yes, sometimes furious titles she chose for her work. But like Emily Dickinson, whom Adrienne Rich notably called ‘Vesuvius at Home,’ Mrs. Taylor’s anger is surpassed by her lyric gifts. Anyone can be angry at the limitations imposed by—oh, dear God, let us outgrow those terms of ‘race, class, and gender,’ but for now, they’re what we’ve got—the hand that life deals us, but Mrs. Taylor has never had any use for whining for a better hand or for looking back at the cards she might have been dealt. In the last letter I received from her, she gave me, as both a consolation for loss and a warning, the best advice of my life, and perhaps my work as well: ‘Unhappiness takes so much time.’” ~Poet Diann Blakely in a 2009 essay for Chapter 16

“Eleanor Ross Taylor’s poetry—the work of a fierce intellect and creative genius—will continue to be truly unique, of a time and far, far beyond it.” ~Claudia Emerson, a professor of poetry at the University of Mary Washington and the author, most recently, of Figure Studies

“I met Eleanor Ross Taylor only once, twenty years ago when Peter Taylor was still alive, and they were both spending the summer in Sewanee. They graciously invited a number of us at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference to their home. She noticed my interest in the photographs on their walls of Peter and herself with friends like Robert Lowell (she called him ‘Cal’) and Randall Jarrell. She was happy to talk about Lowell and Jarrell and the occasions of the pictures. She said nothing about her own poetry, and although I knew that she was a poet, I didn’t know her work well at all. In the years since, I have grown to know and admire her poetry and was able to share my admiration a couple of years ago as I led an Osher session on Southern Poetry Since the Fugitives. I talked to the class about her poems ‘Kitchen Fable’ and ‘How to Live in a Trap.’ People that day were struck by how different she sounded from all the others we’d read. Compressed, funny, and fierce. When the session ended, a friend of hers from college came up to me and told me that Eleanor Ross had ambitions to be a writer even then. All those years married to and being friends with writers who overshadowed her, and now to me, at least, she shines just as brightly.” ~Mark Jarman, creative-writing professor at Vanderbilt University and author, most recently, of Bone Fires

“I met Eleanor Ross Taylor only once, twenty years ago when Peter Taylor was still alive, and they were both spending the summer in Sewanee. They graciously invited a number of us at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference to their home. She noticed my interest in the photographs on their walls of Peter and herself with friends like Robert Lowell (she called him ‘Cal’) and Randall Jarrell. She was happy to talk about Lowell and Jarrell and the occasions of the pictures. She said nothing about her own poetry, and although I knew that she was a poet, I didn’t know her work well at all. In the years since, I have grown to know and admire her poetry and was able to share my admiration a couple of years ago as I led an Osher session on Southern Poetry Since the Fugitives. I talked to the class about her poems ‘Kitchen Fable’ and ‘How to Live in a Trap.’ People that day were struck by how different she sounded from all the others we’d read. Compressed, funny, and fierce. When the session ended, a friend of hers from college came up to me and told me that Eleanor Ross had ambitions to be a writer even then. All those years married to and being friends with writers who overshadowed her, and now to me, at least, she shines just as brightly.” ~Mark Jarman, creative-writing professor at Vanderbilt University and author, most recently, of Bone Fires

“Eleanor Ross Taylor was one of the best American poets of the twentieth century, and I was very lucky to have been a reader of her work and, as an editor, in a position to help it receive some overdue recognition. She gave new and vivid meaning to the expression ‘mother tongue.’ Her poems, and also her silences, were devastatingly eloquent. It will be hard to find work more surprising or redemptive than hers. Eleanor Ross Taylor will always be one of the greatest treasures of American poetry.” ~Don Share, Memphis native, senior editor at Poetry magazine, and author most recently of Squandermania

“Eleanor Ross Taylor, the wife of Pulitzer-Prize winning fiction writer Peter Taylor, kept her wedding photo prominently displayed on the mantel of her Charlottesville home. Poets Robert Lowell and Allen Tate, best man and groomsman, glowed therein. This, and their friends and teachers, was the elite literary society in which she spent her adult life. On her quiet own terms, of course, for Eleanor Taylor was modest and self-effacing in the extreme, like Emily Dickinson, whose poetry she adored. Taylor seemed to have always been a writer (her teacher was Randall Jarrell and his pals) but it would be hard to name a poet whose sound and style was more idiosyncratically her own—bristly, terse, elliptical, sardonic, always with a countrywoman’s tempered experience of hard days and wisdom that is indomitable. A gentle, patient feminist, she believed in her poems and their ability to live beyond her refusal of public readings, teaching forums, conferences, reviews, and the like. Despite that, every year new readers discover this brilliant light around the corner, its luminosity steady. It was a great privilege to be her editor for thirty years, as it was to be invited to her living room for an hour’s gossip. Ms. Taylor, petite and sharp as a fine kitchen knife, remains in those poems whose touch is a careful matter.” ~Dave Smith, a professor of poetry at Johns Hopkins, editor of the Southern Messenger Poetry Series at Louisiana State University Press, and author, most recently, of Hawks on Wires: Poems, 2005-2010

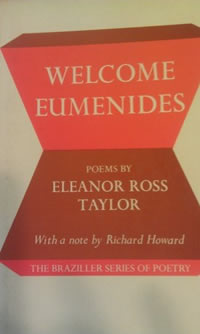

“I still remember my discovery of Taylor’s Welcome Eumenides in a used book store in Chapel Hill when I was just beginning to write. The confessionals were all the rage, but here was an authenticity and originality whispered, elliptical but not coy, fierce and fiercely guarded. I’ve kept going back to her precise and radiant poems for thirty-five years and don’t intend to stop. Taylor’s Captive Voices is a major accomplishment that rewards all the attention it demands. What she has said will not be easily unsaid.” ~R.T. Smith, editor of Shenandoah and author, most recently, of The Calaboose Epistles

“I still remember my discovery of Taylor’s Welcome Eumenides in a used book store in Chapel Hill when I was just beginning to write. The confessionals were all the rage, but here was an authenticity and originality whispered, elliptical but not coy, fierce and fiercely guarded. I’ve kept going back to her precise and radiant poems for thirty-five years and don’t intend to stop. Taylor’s Captive Voices is a major accomplishment that rewards all the attention it demands. What she has said will not be easily unsaid.” ~R.T. Smith, editor of Shenandoah and author, most recently, of The Calaboose Epistles

“[H]er poetry is sui generis, which must be proved on the reader’s pulse. After these pages, you will see first-hand the extreme compression, the teasing shards of narrative, the haunting, disjunctive lyric images, the swift moves from sly indirection to clenched-teeth irony to confrontation, the interleaving of exact speech and the unspeakable.” ~Ellen Bryant Voigt, from the introduction to Captive Voices

“[L]ife is, finally, where any discussion of Eleanor Ross Taylor should begin and end. By all accounts—including her own—Taylor’s life has been full and capacious and treasured. She has raised children and sustained long friendships. She was happily married for fifty-one years and in that time lived deeply within—and, we can now see, cannily slant to—a high-octane literary milieu. That her work often realizes and gives voice to an essential loneliness that is at the heart of making art is no paradox: that loneliness, even for the liveliest among us, is at the heart of being conscious, and being human.” ~Christian Wiman, editor of Poetry magazine, in awarding Eleanor Ross Taylor the Ruth Lilly Prize

To read a selection of poems by Eleanor Ross Taylor in Poetry magazine, please click here. For more updates on Tennessee authors, please visit Chapter 16’s News & Notes page, here.

Tagged: Poetry