On August 28, 2013, President Barack Obama spoke to thousands who had gathered near the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington that culminated in Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. “Five decades ago today,” Obama said, “Americans came to this honored place to lay claim to a promise made at our founding: we hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.”

Joining the president were members of King’s family, former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, and Representative John Lewis, Democratic congressman from Georgia. Lewis is the only surviving member of the eleven speakers who addressed the 250,000 people crowding the National Mall in 1963. At twenty-three, Lewis was the youngest organizer of the March and the youngest to speak that day. Three years earlier, as a seminary student in Nashville, he had organized the Nashville Student Movement, leading lunch-counter sit-ins that galvanized the nation.

Joining the president were members of King’s family, former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, and Representative John Lewis, Democratic congressman from Georgia. Lewis is the only surviving member of the eleven speakers who addressed the 250,000 people crowding the National Mall in 1963. At twenty-three, Lewis was the youngest organizer of the March and the youngest to speak that day. Three years earlier, as a seminary student in Nashville, he had organized the Nashville Student Movement, leading lunch-counter sit-ins that galvanized the nation.

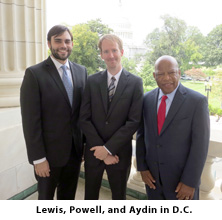

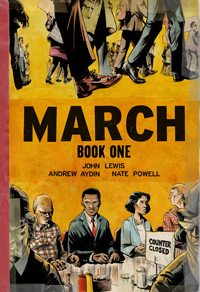

Now Lewis—with the help of his political aid, Andrew Aydin, and artist Nate Powell—has told the story of his life, from his childhood in rural Alabama to the Nashville protests, in a powerful graphic memoir called March. The book is the first volume of a planned trilogy which will conclude with the March on Washington.

The story is framed as a series of flashbacks, with Lewis speaking to a visiting family of constituents on the morning of Obama’s inauguration as the first African-American president. This structure gives March a cinematic feel, and Powell, the Eisner-winning author of several previous graphic novels, deftly adds to its building emotion with visual elements: strong contrasts between light and dark imagery, extreme close-ups and sweeping landscapes, realistic portraits and impressionistic visions of memory. The words interact with the pictures in surprising ways, sometimes in the margins or penetrating the frame of an image, sometimes as tiny white script in a vast sea of blackness, and even once flowing over the body of young John Lewis in three dimensions as he memorizes Bible verses in an Alabama chicken house. There are pages with no words at all, events moving in the style of a film storyboard so engrossing that the reader almost hears a Hollywood soundtrack.

As Lewis has explained recently on The Colbert Report, the idea for March came from Aydin, who in addition to serving as Lewis’s press secretary and social-media manager is also a longtime student of comics and graphic novels. While the Washington memoir—usually weighing several pounds, almost always ghostwritten—is the usual way for a political insider to tell his life’s story, Lewis was receptive to Aydin’s proposal for a graphic nonfiction book because he himself had been inspired by an early nonfiction comic book, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, which he read as a teen.

As Lewis has explained recently on The Colbert Report, the idea for March came from Aydin, who in addition to serving as Lewis’s press secretary and social-media manager is also a longtime student of comics and graphic novels. While the Washington memoir—usually weighing several pounds, almost always ghostwritten—is the usual way for a political insider to tell his life’s story, Lewis was receptive to Aydin’s proposal for a graphic nonfiction book because he himself had been inspired by an early nonfiction comic book, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, which he read as a teen.

On March 26, 1958, Lewis attended a meeting at Nashville’s First Baptist Church where Jim Lawson, a professor in the Vanderbilt University divinity school, described King’s vision and its basis in the philosophy of Gandhi. The comic book detailing King’s use of nonviolent protest in Montgomery, together with Lawson’s speech at this meeting, inspired Lewis to seek justice in segregated Nashville, forever changing the direction of his own life. Shortly thereafter, he began to lead the Nashville lunch-counter sit-ins that form the main plot line of this first volume of March.

Like the acclaimed graphic novels Maus and Persepolis, March is a coming-of-age tale set against a backdrop of violent, historical confrontation. As in those books, the sweep of history is palpable on every page, but it is the prosaic, very human concerns of the protagonist that make the history breathe. In a traditional historical novel, the reader is drawn into the past by the novelist’s tools—characterization, plot, dialogue, and especially description—but in a graphic novel, the engrossing reality of the historical setting is left largely in the hands of the artist. Like Art Spiegelman in Maus and Marjane Satrapi in Persepolis, Powell has created an idiosyncratic visual style that perfectly echoes the times and events portrayed in March. Of course Spiegelman and Satrapi are artists as well as writers, and they illustrated their own works. What is remarkable about March is that it represents a collaboration of three very different people—a senior congressman, a young press secretary, and a seasoned comic artist—yet the finished book is a seamless, engrossing, and ultimately believable story told in the voice of a one man who came of age at a key moment in American history.

“We must never ever give up,” Lewis told the crowd gathered around the Lincoln Memorial again this year, standing in the spot where he and King had stood fifty years before. “We must never ever give in. We must keep the faith and keep our eyes on the prize.” With March, Lewis and his coauthors have created a story that will inspire a new generation with the meaning of that faith and the full humanity of that prize.

Congressman John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, will discuss March at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13, 2013. All festival events are free and open to the public.

Tagged: Children & YA, John Lewis, Nonfiction