It’s not terribly unusual for writers of fiction for adults to try their hands at children’s literature, often with great success. That’s just what Maile Meloy, prizewinning author of two previous novels (Liars and Saints and A Family Daughter) and two short-story collections (Half in Love and Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It), did with her most recent work, a middle-grade novel called The Apothecary. But it’s a rarer thing entirely for a book to come into being the way this one did: after two screenwriter friends dreamed up the storyline, they proposed that Meloy turn it into a novel. To her own surprise, and to the good fortune of readers of all ages, Meloy agreed.

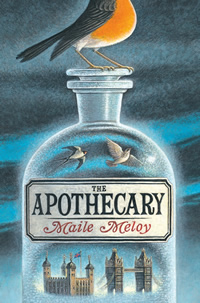

Set in the early Cold War era, in a London still licking its wounds from World War II, The Apothecary follows the adventures of two children. Janie is an American girl who moves with her parents—blacklisted screenwriters—to England; Benjamin is a rebellious boy she meets at her new school. Benjamin dreams of becoming an international spy, and he chafes at the thought that his future more likely holds what he sees as the dull, “poxy” livelihood of his father, a humble apothecary. But thanks to Benjamin’s precocious surveillance skills, he and Janie soon discover that there’s more to his father’s mixing of powders and liquids than meets the eye. When the apothecary’s shop is ransacked, and he vanishes, the two new friends embark upon a mission not only to find him but to head off a nuclear disaster. Appropriately, this requires the use of several magical, matter-altering potions, including the aptly and delightfully named “Smell of Truth,” and an avian elixir that briefly transforms those who imbibe it into birds.

Magical and historical in equal measure, The Apothecary is an intelligent, deftly plotted novel that might easily win a kid over to books for a lifetime—that is, if her parents don’t swipe it from her first. The book, in other words, is right on trend as a work with enormous crossover appeal. But even adult readers who are skeptical of that trend in popular fiction are likely to fall in love. Reviewing the book for The New York Times, Kyrstyna Poray Goddu admits that, though she is “predisposed against the genre,” she nonetheless found it “a happy surprise.” The Apothecary, she concludes, offers “the same emotional resonance that has won acclaim for [Meloy’s] adult fiction, grounding her story in the intricacies of family love, friendship and loyalty, blended here with the complicated fluctuations of adolescence.”

Meloy recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Meloy recently answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: The Apothecary is generously peppered with references to classic literature—work by Dickens and Henry James, for example—and it elegantly folds in a lot of World War II and Cold War history. It almost seemed that you were slyly and adroitly coaxing your young readers into the larger worlds of literature and history, under the guise of a magical tale. Was this educational element intentional?

Meloy: When I started, I was trying mostly to entertain. But the Cold War in the early fifties is a time that middle-school kids know almost nothing about (and that many adults don’t know much about), so there were things that needed to be explained. If the novel leads them to be more interested in our history, that’s thrilling.

Similarly, the literary references were there because the characters are readers, so they talk about books. And I wanted to add layers for adult readers, so that people of any age could read the book. But I love the idea that The Apothecary might lead a kid eventually to Henry James or Jane Austen, out of curiosity.

Chapter 16: In an essay for The Wall Street Journal, you mentioned that writing for children “felt like coming home,” and that it helped you understand “why so many adults have started reading books written for kids. That’s where the plots are.” In what ways has writing a middle-grade novel changed the way you’ll think about your future work for adults?

Meloy: Clarity and plot have always been important to me, and they’re especially important in writing kids’ books, which is why I think it felt natural to make the switch. I’m just finishing another novel about Janie and Benjamin, so I haven’t written another one for adults yet, and don’t know how those books will be affected. But I’ve had to pull back from both kids’ novels repeatedly to look at the structure, and to think about the puzzle-like nature of a complicated adventure plot. That’s good practice and I’m sure it will be useful.

Chapter 16: In the book’s acknowledgements, you explain that the spark for The Apothecary came from two friends who initially envisioned this story as a film. Has your adult fiction ever begun in similar circumstance—a story idea passed along by friends or family—or complete strangers, for that matter? Many writers have been approached by readers who say, “I have this great story idea and I think you should write it!” but I’ve never heard of a writer who agreed.

Meloy: I’ve never done anything quite like this before. The Apothecary caught me at a vulnerable moment, when I had just finished Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It and didn’t know what I was going to do next, and it seemed particularly interesting and challenging.

Meloy: I’ve never done anything quite like this before. The Apothecary caught me at a vulnerable moment, when I had just finished Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It and didn’t know what I was going to do next, and it seemed particularly interesting and challenging.

But everything comes from somewhere, and I’ve used suggestions in smaller ways before. My husband had a dream that his dead grandmother showed up alive, so I wrote a story (“Liliana”) about a dead grandmother who shows up on the doorstep. When I was first writing stories, someone complained that my male characters were all stoical westerners with one-syllable names like “Chet” and “Cort” and he wanted to see a talkative Samoan with a long name, so I put a Samoan character in the next story I wrote (“Tome”). I take requests.

Chapter 16: Were you aware of the Chelsea Physic Garden before you started working on this story? At what point did you decide to include it as a setting? It’s one of those beautiful instances of the real world giving you exactly what you need—and I love to think of the young readers who will be compelled to visit the gardens!

Meloy: I had never heard of it before, but it was a perfect setting: it was started by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London in 1673, and it still grows medicinal plants from all over the world. After I’d written a first and maybe a second draft of the book, I went to visit the garden. It’s an amazing place, and has a mulberry tree you can hide inside: I added that to the book after going there. But my Chelsea Physic Garden still has some elements that I made up, that aren’t really there. There’s no sundial, and no gardener’s cottage.

The first group of kids I talked to about The Apothecary included a boy who was going to London, and his family changed their trip to include the Chelsea Physic Garden and the Imperial War Museum, my favorite museum, where I did research. I love the idea that kids (and adults) might go to both of those places because of the book.

Chapter 16: On several occasions the main characters in The Apothecary drink an “avian elixir” and morph, briefly, into birds. Janie’s a robin; Benjamin, a skylark; Pip, a swallow. Why these birds for these characters?

Meloy: Janie became a robin because I wanted a particularly American bird for her, one who was appealing and energetic but not showy. Benjamin became a skylark because they’re brash and defiant, and they have a distinctive crown of feathers, like Benjamin’s hair. Even the word “skylark” has a dash and brightness to it. Pip is a swallow because they’re quick and graceful and acrobatic—and small.

Chapter 16: You mentioned that you’re working on a new book featuring Benjamin and Janie. Any hints about their next adventures?

Meloy: The next book starts in 1954, a year after The Apothecary ends. Janie is in boarding school in the United States because parents, especially good and loving and beloved parents, are a real hassle when you’re writing a kids’ adventure story. I had to get rid of them so that Janie didn’t have to keep checking in. She’s sixteen and wants to be a chemist like Jin Lo, and is working on a chemistry project. Benjamin is off with his father saving the world, and Janie doesn’t know where he is. That’s where it starts.

[This interview appeared originally on April 17, 2012, and has been updated to reflect Maile Meloy’s forthcoming Nashville appearance.]

Maile Meloy will appear at Parnassus Bookson October 3, 2013, at 6:30 p.m. to read from The Apprentices, her newly released sequel to The Apothecary.

Tagged: Children & YA