In the way of most seventeen-year-olds, young Morgan Kinneson is certain about life. As the Civil War rages far away, his family of Vermont abolitionists holds to its beliefs by being a critical stop on the final leg of the Underground Railroad. When an elderly runaway named Jesse Moses is killed by slave hunters while under Morgan’s care, the guilt-stricken youth vows to avenge the slave’s death. Instead, he finds himself on the run from the same pack of slave hunters, protecting a rune-covered stone that Moses had slipped into his pocket. Unaware of the stone’s full significance, Morgan nonetheless recognizes the need to keep it safe. Thus begins the journey at the heart of Howard Frank Mosher’s Walking to Gatlinburg, his beautifully written and utterly engrossing tenth novel.

On the run, Morgan wants desperately to learn the whereabouts of his revered older brother, Pilgrim, a Union doctor who has been missing since Gettysburg. His plan is simply to go to the battlefield and try to find some evidence that his brother is either alive or dead. What he finds there keeps him pressing further south, but he is sidetracked by a host of characters and events, including a love affair with an escaped slave named Slidell (who is perhaps a bit conveniently young and beautiful). Morgan’s quest to find his own brother is diverted by his efforts to help Slidell rescue her younger brother from the Tennessee plantation from which she has escaped.

For a time the stone, the slave hunters, Slidell, and the war itself conspire to keep Morgan from the search for Pilgrim. We know these concurrent threads must eventually cross one another, and the patient reader is rewarded when they do come together, although not so neatly as to seem at all contrived.

For a time the stone, the slave hunters, Slidell, and the war itself conspire to keep Morgan from the search for Pilgrim. We know these concurrent threads must eventually cross one another, and the patient reader is rewarded when they do come together, although not so neatly as to seem at all contrived.

There is a fine line between Odyssean tragedy and Forrest Gumpian absurdity, and Mosher walks this line astonishingly well. Despite the fact that Morgan meets, at various points, Abraham Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, a traveling magician with a pet elephant, the purported slave son of Thomas Jefferson, and a family of Melungeons that may or may not be ghosts, the propulsive power of the story and the grounding realism of the language render this narrative utterly believable.

Lovers of the English language, particularly of Shakespeare, will find much to appreciate here. Mosher’s book is lyrical and expressive even when portraying a brutal war. Consider the moment that Morgan finds himself on a hillside in a rainstorm, when the ground begins to slip away:

Corpses clad in gray and corpses clad in blue, mortal enemies in life, boon companions in death, tumbled down the slope in moribund embrace only to be swept away by the freshet at the foot of the hill. … The bones danced a macabre supine dance and clicked together like handheld spoons at a hoedown. Some of the deceased seemed to be racing each other down the hillside. One poor soldier, mere rags on bone, was hung up in a pawpaw tree whose roots had pulled out of the bank. A skull came bowling down the slope, greenish white in the liquescent light. It clacked off another skull like a billiard ball, took a merry skip, and landed at their feet.

As Morgan travels deeper into the Appalachians, Mosher treats readers to a sensory appreciation of what would naturally have been a stupefying wonderment to a young man traveling far from home for the first time: “Morgan ascended into the mountains through folds and creases bright with blossoming rhododendrons and azaleas. At close range the metallic colors made his head spin. What was the point of all this riot of color?” The further he travels into the mountains, the more the war fades as a backdrop to his story. We meet instead the mountain people, who are survivors, storytellers and warriors of a different order: “No one else spoke. No one pledged peace or offered to shake hands with friend or foe. Such was not the way of these people.”

The stories of men at war are of course as old as the men and the wars themselves. A gifted storyteller, Mosher converts a timeless story into one that is fresh, vibrant, and compelling. This alchemy begins with the creation of a character like Morgan Kinneson, so certain when his journey begins at age seventeen—and forever uncertain when it ends at age eighteen. “This world,” he thinks to himself, “this woeful, wondrous world.”

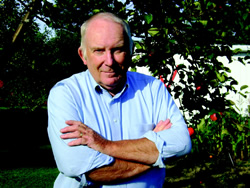

Mosher will discuss Walking to Gatlinburg at Davis-Kidd Booksellers in Nashville on March 21 at 4 p.m.

Tagged: Fiction