Overcoming Obstacles

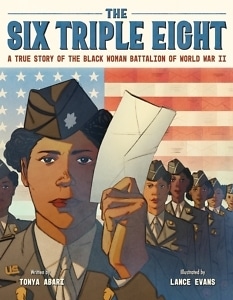

Tonya Abari’s The Six Triple Eight delivers a compelling piece of WWII history for children

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, known as the “Six Triple Eight,” was a predominantly Black unit in the U.S. Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during World War II. In February 1945, these women were sent to England to confront a daunting task: sorting and delivering millions of pieces of mail for U.S. troops that had piled up during the war. They completed the job well ahead of schedule, then successfully tackled another enormous backlog of mail in France, driven by their dedication to boosting the morale of weary soldiers.

The stellar work of the 6888th was achieved during the era of segregation, when Black women had to struggle for the opportunity to serve their country. Nashville-based author and educator Tonya Abari’s The Six Triple Eight: A True Story of the Black Woman Battalion of World War II turns their story into an inspiring, empowering history lesson for children. As Abari puts it, the book is “about sometimes having to face obstacles on the road to doing something great.”

Tonya Abari answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: The 6888th has been honored by the White House and with a monument at Fort Leavenworth, and it was the subject of a Netflix film directed by Tyler Perry. How did you first encounter the story?

Tonya Abari: In 2018, when my oldest daughter was about 3, I saw the story about the monument and dedication on CBS Morning News. Being military adjacent (many members of my family served), I was completely inspired. At the same time, I was also disappointed that I’d never even heard of the Six Triple Eight. This story was nowhere to be found in the history books. And these women deserved to be there. So, I searched for a picture book to read to my daughter — one that she could keep and grow with (understanding our history is important in this house). I couldn’t find a single book for young readers about the Six Triple Eight.

At that time, I was a participant in a picture book program called 12×12, where we wrote 12 manuscript drafts over the course of 12 months. It was during my second time signing up for this program that I wrote the draft for The Six Triple Eight. Of course, I didn’t have an agent, wasn’t connected with any editors, and still was very new to the business of publishing. I put the manuscript away, and it resurfaced in 2020 when I signed with a literary agent. It was on submission for nearly a year and was picked up by HarperCollins in 2021. (Yes, it often takes that long for a picture book to be published!)

Chapter 16: What aspects of this particular piece of history make it an important story for children to know?

Abari: War is a very complex topic, especially for children. But we often don’t hear about the small nuances that happen behind the scenes. These women provided the glue for families by ensuring that soldiers and their loved ones could communicate. This boosted the morale of the troops and gave them hope.

Alongside the themes of resilience in the face of oppression, I want children to know how much letters meant to people. And that even with the advancements in technology and the shift away from handwritten letters, young people can appreciate the gratitude that comes from receiving or sending a letter.

Chapter 16: The story of the 6888th is one of collective achievement and empowerment, but it also involves the ugly history of segregation. How do you approach balancing those themes for children?

Abari: Children exist in a world in which these events have happened and still are happening. I often think about the children who endured chattel slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow. Children as young as 5 years old experienced racism and hate in both subtle and demonstrative ways. If they were old enough to experience it, children are old to learn about it. Exploring these themes side by side is really a reflection of the human existence. There’s joy alongside pain. There’s achievement alongside failure. There’s oppression in the shadows of empowerment. The book is a celebration of women’s contributions, but a life lesson that even children experience at young ages is about sometimes having to face obstacles on the road to doing something great.

Abari: Children exist in a world in which these events have happened and still are happening. I often think about the children who endured chattel slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow. Children as young as 5 years old experienced racism and hate in both subtle and demonstrative ways. If they were old enough to experience it, children are old to learn about it. Exploring these themes side by side is really a reflection of the human existence. There’s joy alongside pain. There’s achievement alongside failure. There’s oppression in the shadows of empowerment. The book is a celebration of women’s contributions, but a life lesson that even children experience at young ages is about sometimes having to face obstacles on the road to doing something great.

Chapter 16: Lance Evans’ illustrations, especially his color choices, really seem to capture the World War II era. Are there elements of the artwork you especially like?

Abari: Lance Evans is such a talented artist. I won’t embarrass myself by pretending that I know about illustration techniques, but the colors framed the story perfectly. I really appreciated Lance’s thoughtful expressions throughout the manuscript. Additionally, making the letters into their own character by sprinkling them throughout was a nice touch. The end papers really made me tear up, seeing every single last member of the 6888th’s name written out for everyone to see.

Chapter 16: I believe this is your fourth children’s book, with more on the horizon. What keeps you writing for kids?

Abari: Although I also write for adults, I really enjoy writing for children. My own children are still very young (11 and 4), and I am pretty sure a big part of my life’s work is helping children to see themselves and the world around them through reading. As a parent and as an educator, I’ve experienced literature opening so many doors for children. I’ve witnessed non-readers transition into voracious readers. I’ve seen students get excited about history and books. Their inquisitiveness is actually pretty inspiring. Young people have this innocence to them; they are always curious. And it warms my heart to know that just with a few words, I could have an impact on the way stories continue to be told for generations to come.

Chapter 16: Efforts to censor books and reshape history are perennial challenges in our culture and politics, and they are certainly at the forefront today. How do you see your work in light of those challenges?

Abari: I live in a state that is third on the list of total banned books across the entire country. Most of these bans unfairly target authors who carry certain identities. When we think about banning books — preventing students from engaging in literature — we are shrinking their world view. That impacts their values and jeopardizes their ability to empathize with humans from all walks of life. I, myself, am a truth seeker and I have been guided to do the work of preserving and celebrating my culture through writing. I stand on the shoulders of visionary creatives who have created during unfathomable circumstances. Authors like Toni Morrison, Toni Cade Bambara, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks shaped my resilience as a writer.

I’m also ecstatic to be writing children’s books among talented contemporaries who, despite the many challenges in publishing, are still passionate about storytelling. And that’s what keeps me motivated. In whatever medium I can — writing, reporting, oral storytelling — I will persevere. Although I can’t deny that I’m writing for my younger self, I’m primarily doing this for young readers and for the subjects whose stories deserve to live on.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.