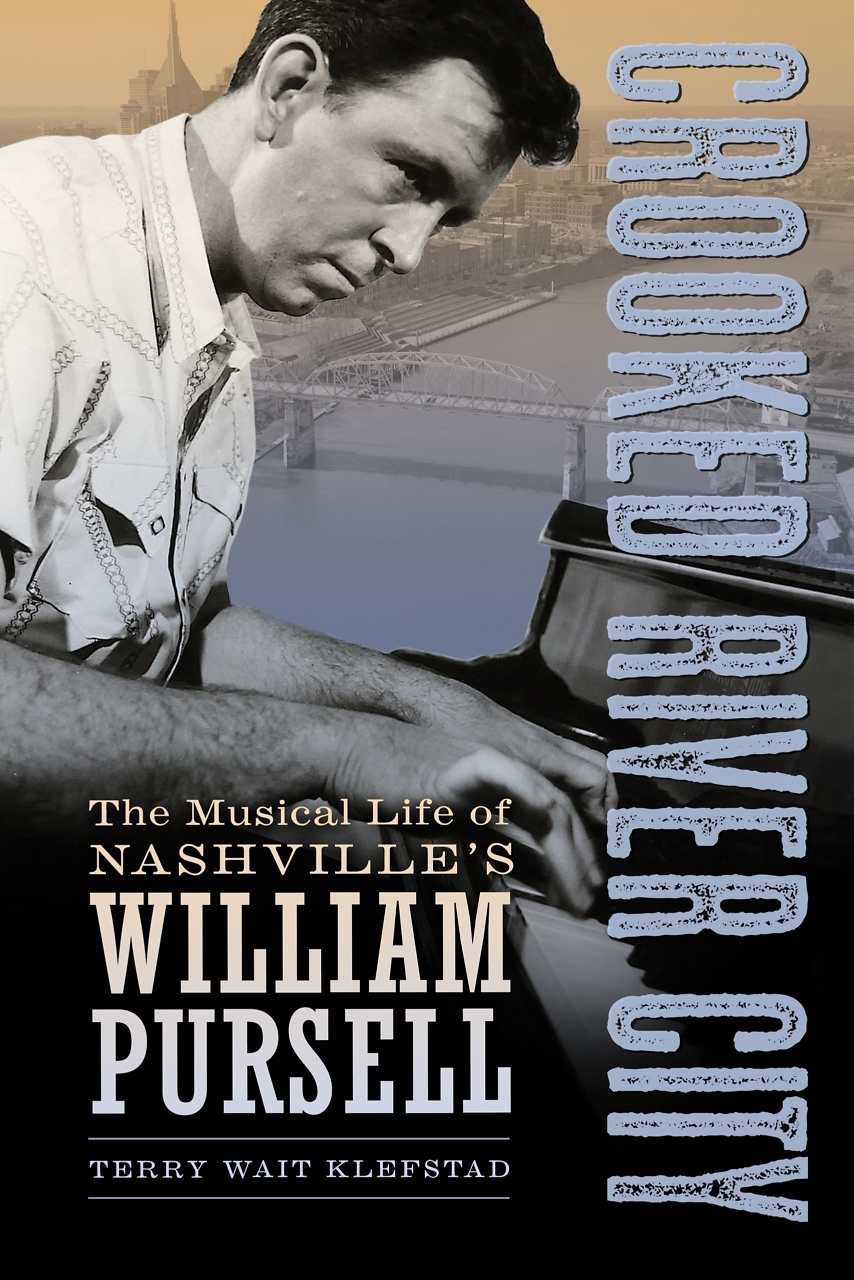

Heartbreak at the Core

Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies is the story of a complicated marriage

Lauren Groff’s third novel, Fates and Furies, is a complicated animal—part love story, part tragedy, part black comedy. It surveys the long marriage of a golden boy to a mystery girl, focusing on husband and wife in turn. The shift in perspective brings revelations that muddy as much as they clarify, leaving the reader to ponder the possibility that a couple can love profoundly without ever really knowing each other at all.

Lancelot “Lotto” Satterwhite, born in the eye of a Florida hurricane, grows up rich and cosseted, at least until his millionaire daddy dies. His mother, Antoinette, soon breaks his heart by converting the family business and homestead to cash, thus depriving young Lotto of all material link to his father. “It’s yours and your sister’s,” Antoinette tells the boy by way of justification. “It’s all in trust for you.” A couple of years later, in another this-is-for-your-own-good act of cruelty, she packs Lotto off to a New Hampshire boarding school to get him away from friends she deems undesirable. Antoinette carries on this high-handed approach to mothering through the years, ultimately shaping—or seeking to shape—her son’s life.

Lancelot “Lotto” Satterwhite, born in the eye of a Florida hurricane, grows up rich and cosseted, at least until his millionaire daddy dies. His mother, Antoinette, soon breaks his heart by converting the family business and homestead to cash, thus depriving young Lotto of all material link to his father. “It’s yours and your sister’s,” Antoinette tells the boy by way of justification. “It’s all in trust for you.” A couple of years later, in another this-is-for-your-own-good act of cruelty, she packs Lotto off to a New Hampshire boarding school to get him away from friends she deems undesirable. Antoinette carries on this high-handed approach to mothering through the years, ultimately shaping—or seeking to shape—her son’s life.

Lotto winds up at Vassar, where his charm and endearingly flawed good looks make him, in college-boy parlance, “Master of the Hogs.” (In other words, he screws lots of girls.) He thinks of himself as “an antipriest, devoting his soul to sex.” His string of conquests ends when he meets Mathilde Yoder, a friendless, beautiful ice queen of a girl, who strikes him as “Olympian, elegant on her mount.” They quickly marry and commence a life of struggling young couplehood in New York—Lotto an aspiring actor, Mathilde the dutiful breadwinner. They surround themselves with a coterie of old friends and frenemies, some of whom turn out to be far more menacing than they first seem. Lotto confines his prodigious sexual energy to the conjugal bed, and Mathilde has no trouble keeping up with him. Theirs is a passionate marriage.

The novel is delivered in third person, with bracketed asides providing Greek chorus-like commentary, but it focuses primarily on Lotto’s perspective for its first half, then turns the second half of the book over to Mathilde. Lotto’s version of the marriage is a sweet, though not entirely untroubled, love story. He considers Mathilde a supremely good person who gently controls him—a sort of benign, lustful puppet master: “All the strings led to Mathilde’s pointer finger, and she moved it with the subtlest of twitches and made him dance.” Lotto is not a bad guy, but he’s afflicted with a kind of innocent arrogance. When he goes almost overnight from failed actor to successful playwright, it seems to him no more than his due. If Mathilde’s energies are devoted to his care and feeding, well, it makes her happy to do things for him. “And what piece of jerk chicken,” he says, “would condescend to say that she was lesser for not being the creator of the family?”

The novel is delivered in third person, with bracketed asides providing Greek chorus-like commentary, but it focuses primarily on Lotto’s perspective for its first half, then turns the second half of the book over to Mathilde. Lotto’s version of the marriage is a sweet, though not entirely untroubled, love story. He considers Mathilde a supremely good person who gently controls him—a sort of benign, lustful puppet master: “All the strings led to Mathilde’s pointer finger, and she moved it with the subtlest of twitches and made him dance.” Lotto is not a bad guy, but he’s afflicted with a kind of innocent arrogance. When he goes almost overnight from failed actor to successful playwright, it seems to him no more than his due. If Mathilde’s energies are devoted to his care and feeding, well, it makes her happy to do things for him. “And what piece of jerk chicken,” he says, “would condescend to say that she was lesser for not being the creator of the family?”

Lotto’s love story gets a major overhaul when the focus turns to Mathilde. Her backstory, which she sketched in only a vague way to her husband, turns out to be a doozy. We get one revelation after another about her, the marriage, and Lotto’s stellar career; almost everything we thought we knew is cast in a new light. Vengeance becomes a major theme, and the uncomplicated love that was so central to Lotto’s world is revealed as something murkier, though nevertheless genuine.

It all has the deliberately heightened quality of a Greek tragedy, and, in fact, portions of the story are conveyed through Lotto’s plays, in which mythological themes loom large. Implausible plot turns that would be unforgivable in straight realism—convenient deaths, a sudden flash of genius, readily blackmailed villains—work here because Groff is after something grander than depicting the small drama of Lotto and Mathilde. She’s asking the reader to look hard at all manner of assumptions about love and art, and to consider that even our interior lives are often molded by things we can’t necessarily know or control.

That said, Fates and Furies is neither heavy nor bleak. It’s full of wit and smart banter, contains a hefty dose of sex, and zips along on the smooth rails of Groff’s sophisticated prose. It aims to entertain and succeeds, all the while holding heartbreak at its core.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.