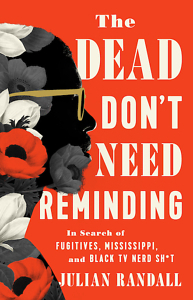

“Mississippi is all arrivals. Mississippi is all beginnings. But Mississippi is also something we return to, again and again, to find where we started in hopes of catching a glimpse at how we might end,” Julian Randall writes in “Oxford,” the opening essay of his memoir, The Dead Don’t Need Reminding: In Search of Fugitives, Mississippi, and Black TV Nerd Sh*t.

Comprised of braided essays which use key pop-culture moments to weave together stories of triumph and personal exploration, Randall writes about returning to Oxford, Mississippi, unearthing grief, deeply rooted family histories, and a resilience that has been shared through the DNA of his forefathers who emigrated from the smothering oppression and racial violence of the deep South.

Randall, who refers to himself as a “noted Chicago supremacist,” spent his formative years in Atlanta and most of his life thereafter in the Midwest. While wrestling with the person he was becoming, Randall said he often theorized that “Southern familial roots were likely completely and forever lost.” However, while he didn’t have the luxury of learning about his family through the oral storytelling that is pervasive in Black Southern communities, Randall always felt a profound sense of connection to the Mississippi soil on which his ancestors lived.

“It was important for me to concede from a very early standpoint [in the book] that I am of Mississippi, but not from there. Although I have been in the Midwest for the vast majority of my life, the farthest I can trace back my family roots begins and ends in the South,” Randall said, explaining how he identifies with the state.

In the book, Randall also seeks to liberate an often-skewed narrative of what it means to be from the South. “I came out as a queer person right before I moved to Mississippi,” he said, “and [among outsiders], there’s this presumption that I moved into this den of vicious hatred, but what [Mississippi] actually is, is a laboratory of Black liberation.”

“I found more Black queer boys than I dated during my entire Northeastern liberal arts college experience. You’re gonna tell me that that is not a place where people find their own way to be free, just like anywhere else in this country? So, it was very important to me that the book unspooled notions of what is actually going on in Mississippi,” Randall said, noting particularly challenging narratives about Black Mississippian boyhood and manhood.

“There is no way to speak about the progress that is made during the Civil Rights Movement and not speak about Fannie Lou Hamer, or not speak the names of countless Black Southerners who have led consistently the way forward. … I knew that I was going to write about [Mississippi], because this place knows me. I’ve lived there. And it changed me and it affects me to this very day.”

“There is no way to speak about the progress that is made during the Civil Rights Movement and not speak about Fannie Lou Hamer, or not speak the names of countless Black Southerners who have led consistently the way forward. … I knew that I was going to write about [Mississippi], because this place knows me. I’ve lived there. And it changed me and it affects me to this very day.”

“To tell the story I take it back another generation / Make sure you haters taste the history of my desperation,” recites Randall in the essay, “Put Me On: An Essay in 16 Bars.” The book’s use of poetic language and wit is both stunning – and, according to Randall, highly intentional.

“Access to beauty is a bit more of a political issue than we talk about. The ways that poetry shows up for me are tied to this amazing poet, Reginald Shepard, who I believe is vastly underread. Jericho Brown introduced me to one of Shepard’s essay collections, Orpheus in the Bronx. In it, he has a number of essays that are all incredible. But the one that I have kind of latched on to over the last half a decade or so is called “Notes Toward Beauty.”

In his essay, Shepard writes, “[B]eauty presents us with the possibility of things as they should be,” and Randall embraces this idea. “At its best, language can correct small political injustices in the ways that we are able to revisit and review things,” he said.

Representation informs the ways in which we think about ourselves, and in “#JULIANFORSPIDERMAN,” Randall takes the reader through the multiverse. In many ways, the evolution of Spider-Man/Miles Morales mirrors Randall’s own coming of age story. In fact, all of Randall’s literary work (for both children and adults) is an unabashed display of his full personhood, as well as a series of love letters to the queer, Dominican, and Afro-diasporic communities that raised him.

“When I was a child, there was a certain level of interiority that I was presumed to simply not have access to,” said Randall of his motivation for writing with representation in mind.

“In The Dead Don’t Need Reminding, I’m attempting to right a historical record that has not only been incorrect, but has also been destroyed. I am also recreating the story of [as well as my understanding of] my great-grandfather. Doing both simultaneously is something that can only be achieved with a level of interiority, that public policy and public representation often do not afford to Black people — especially to queer Black people like myself,” Randall said.

In addition to Jericho Brown and Reginald Shepard, Randall unapologetically gives flowers to the many poets and writers who have helped to shape the writing of this book, including Kiese Laymon, Hanif Abdurraqib, Claribel A. Ortega, Angie Thomas, Nate Marshall, and others.

“The work of Vievee Francis, not only as a poet, but as an educator saved my life and changed my life,” Randall said. “She did not return me to the circumstances of silence and frustration that I was in, she gave me hope and a purpose as well as a model of unrelenting honesty…I cannot say enough about what it means to be contemporaries with someone like Francis.”

“The work of Vievee Francis, not only as a poet, but as an educator saved my life and changed my life,” Randall said. “She did not return me to the circumstances of silence and frustration that I was in, she gave me hope and a purpose as well as a model of unrelenting honesty…I cannot say enough about what it means to be contemporaries with someone like Francis.”

“And I cannot forget to mention Nashville legend, Tiana Clark. Her collection, I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood, has been a huge influence for me. Our debut books came out at the same time. There are a million things to say about the depth, brilliance, and gravitas of Clark’s craft, but the impact of her poems is equally supported by the generosity of her spirit.”

Randall also wants readers to know this memoir would not be possible without writing fellowships like The Watering Hole. He credits the writers in his cohort (like Nicholas Nichols and Itiola Jones), as well as the organization for providing the necessary space for queer Black creatives to write.

“A fellowship in the South saved my life. It is the moment that I recognize proclaiming as the moment that I decided to fight my way back from the darkness.”

When asked what the future of storytelling looks like, Randall said, “It ain’t bright, but it’s warm.”

There is a larger underlying theme explored heavily through Randall’s pursuits which answers this question: What world will be left of us in the aftermath of the stewardship of oppression?

“But I have unrelenting faith in the liberation of the people…and boundless hope that the oppressed will find their way towards freedom,” Randall, further citing that this sentiment is derived from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. who said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

The essence of the memoir is captured in its last sentence, where Randall writes, “In the glowing rain I exhaled and gunned the engine — I laughed my grandmother’s laugh into the Mississippi sky until the clouds became a memory and I was finished haunting my own name.”

“The most satisfying part of writing The Dead Don’t Need Reminding was writing the ending of the book. … The line came to me in the middle of the night and kept trampolining on my temples for days on end. ‘Haunting of my own name’ is [kind of] the theme of the entire memoir. Once I inserted this phrase, I knew the book was done – and it made me feel really proud.”

Reflecting on the type of readers Randall wishes to reach, he said, “Anybody who has or is in the midst of surviving the unsurvivable. I’m here to listen. I’m here to hold you. I’m glad you’re still here.”

Tonya Abari is a Nashville-based independent journalist, author, essayist, book reviewer, and homeschooling parent. Her words have been published in the Nashville Scene, Essence, USA Today, Publishers Weekly, Parents, Good Housekeeping, PBS Kids, and many more. You can find her hanging out on Instagram @iamtabari.