An Artificial Village

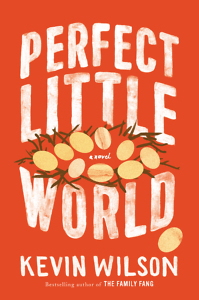

Book excerpt: Perfect Little World

One of Mrs. Acklen’s assistants appeared in the waiting room. “Miss Brenda is ready to see you,” she said, and Preston immediately stood, took one last look at the painting to his left, the colors deeper than bloodstains, and followed her into something of which he could not, having tried many times, anticipate the outcome.

There was no art in the room, no sign of papers or office supplies, no evidence that the room was even used on a daily basis. The only furniture in Mrs. Acklen’s office was a desk with a chair on either side, one of which was currently occupied by that very woman. Though she was in her eighties, she seemed much younger, her body lean and suggesting a lifetime of good choices and moderate exercise. She wore a faded pair of red khakis and a chambray shirt with a blue-and-white bandanna tied around her neck, as if she were a cowboy in the old west. In one hand, she held a glass tumbler of what looked to be iced tea and, in the other, she held a copy of Dr. Grind’s book, The Artificial Village.

There was no art in the room, no sign of papers or office supplies, no evidence that the room was even used on a daily basis. The only furniture in Mrs. Acklen’s office was a desk with a chair on either side, one of which was currently occupied by that very woman. Though she was in her eighties, she seemed much younger, her body lean and suggesting a lifetime of good choices and moderate exercise. She wore a faded pair of red khakis and a chambray shirt with a blue-and-white bandanna tied around her neck, as if she were a cowboy in the old west. In one hand, she held a glass tumbler of what looked to be iced tea and, in the other, she held a copy of Dr. Grind’s book, The Artificial Village.

“Dr. Grind,” she said, not standing, no available hand to offer for a handshake, “I am so happy to finally meet you.”

Preston replied that he was happy to meet her as well and then awkwardly sat down in the unoccupied chair and tried very hard to understand what was going on and why he had agreed in the first place to meet with her. Did he think she was going to give him a billion dollars? He did not need a billion dollars. But why else would he be here? He decided that it was simple curiosity, the hope that someone important might need his expertise. It was, after all, what he spent his life doing, offering his expertise to people who seemed to desire it. It was how he made his living, not a billion dollars, but enough that he considered himself to be fairly rich.

“I have read and reread this wonderful book of yours,” she said, holding the book out to him as if she was unsure if he was aware that he had written a book at all. “It is so enlightening and really gets to the heart of something that I care about very deeply.”

“Thank you so much, Mrs. Acklen,” Preston replied. “It’s very gratifying to hear that.”

“I wondered, if it’s not too much trouble, if you might sign it for me?” she asked him.

“I wondered, if it’s not too much trouble, if you might sign it for me?” she asked him.

Suddenly, it dawned on Preston that this might be the entire reason that he was summoned to Knoxville. A billionaire wanted her book signed. “I can do that, Mrs. Acklen,” he said.

“Let me get you a pen,” she said, opening the desk drawer and then frowning. “There’s no pen in here. Well, damn it. They keep this office for me if I ever have official business, though I rarely do, but, still, someone is supposed to keep the desk stocked with supplies. Samantha!” The assistant stepped back into the room. “Yes, ma’am?” she asked.

“I need a pen.”

The assistant was holding a pen, though she seemed slightly reluctant to part with it, and handed it to Mrs. Acklen, who then handed it, and the book, to Preston. With no precise idea of how to personalize the book, he merely signed it and wrote “with warm regards” and then handed the book to Mrs. Acklen and the pen to her assistant, who took it and then disappeared from the room.

Preston and Mrs. Acklen sat for a few seconds in silence, both of them smiling, the air-conditioning rattling softly. Finally, Mrs. Acklen leaned over the desk, looking directly at Preston. “I imagine you’re a little confused as to why I asked to meet you,” she said and then nodded as if there was no need for him to respond because she already knew the answer. Still, Preston could not help but nod in agreement. “I was wondering what the main objective might be,” he admitted, “but of course it’s also an honor to meet you.”

“Nothing special about me,” she said. “But you . . . you are something else. After I read your book, a little later than everyone else did, I admit, I knew that you were someone who had designs on improving the world, of doing something important. And, in my old age, doing something important really appeals to me.”

The book she was referring to, The Artificial Village, sought to outline how, as nuclear families became less traditional and people were less likely to spend their lives in the same geographic location, surrounded by their relatives and neighbors whom they’d known for their entire lives, children, especially babies and toddlers, were finding fewer and fewer possibilities for meaningful human interaction. The book offered several new ways of thinking about community building, of how to create villages in seemingly inhospitable circumstances. Grind’s primary focus was on inner-city and rural areas, where the need for childhood development was greatest, and he traveled the country to help government agencies design programs to encourage a more communal relationship among seemingly random families. He had met Oprah, who had endorsed his book and ideas, which was about as much fame as a child psychologist could hope to gain. When so many of his colleagues were focused on teenagers, trying to explain the rise in drug use and violence, Grind focused on toddlers, on those first five years of life, when a few adjustments could, he asserted and numerous studies had proven, make a huge difference. The worry was all about schools and how they could properly prepare youths for the future, when children from birth to age five were pretty much ignored. There had to be a way, he posited, to make the first years of a child’s life as easy and as protected as possible, regardless of circumstances.

It did not escape Grind’s awareness, or those who looked to write stories about him, that his work seemed to be a direct response to his own parents’ methods of child rearing. “Every parent,” he would often say, “believes they are working in the best interests of their children. And sometimes this is true. Sometimes it is not. Sometimes we need other people to help us.”

He had received several grants, a substantial amount of money, to test his theories, and he focused on a few neighborhoods, finding ways to link new parents and their children, putting aside resources for child care and development, getting those without children or who no longer had children within the age range involved in outreach with their neighbors, and, finally, providing communal spaces for interaction and growth. Initial studies had shown significant improvement in the development of these children, regardless of socioeconomic background or family history. For Grind, however, it wasn’t enough to get people to see their neighbors as potential sources of support, he wanted them to see each other as members of a singular family, but this seemed troubling to his colleagues, moving into a kind of new-age therapy, and so they continued to focus on hard data and scientific methods.

Well,” Preston replied, his pale skin, he could feel it, turning deep red with embarrassment, “I don’t know how successful it ultimately will be. It requires long-term studies, and further testing has found new issues that we’ll have to address moving forward.”

It was a habit that he found difficult to break, the way he talked about the work as if he was still a part of it, as if he had anything to do with the studies now, having removed himself from all of it.

“I mean, rather, that someone else will have to address. I am, as you may or may not know, no longer directly involved in the Artificial Village project. My name is still listed as an advisor, but I couldn’t tell you exactly what the status of the project is at the current moment. If you want to become involved in it, I know they would appreciate your support. I could put you in touch with the proper people.”

“Dr. Grind, I am very much aware of your circumstances,” Mrs. Acklen said. “I have quite a bit of time to devote to my interests; I do my research. No, while I think it is worthwhile and deserves attention, my interest is not with the Artificial Village project. My interest is, to be frank, with you.”

Preston’s face grew even hotter, a heat wave passing through his system. Was Brenda Acklen coming on to him?

“I’m flattered, Mrs. Acklen,” he responded.

“Call me Brenda, please,” she said, smiling.

“Only if you call me Preston,” he said.

“Certainly,” she replied. “No need for formality here.”

“Well, I’m very honored to meet you, as I said earlier, and I’m very grateful to hear your kind words about my work. I’m just not sure what it is I can do for you, why I’m here.”

Mrs. Acklen took a sip from her iced tea. “Preston, could I tell you a story? Do you have time for that?”

Preston felt like time had stopped, that he had entered some kind of vortex when he stepped into Mrs. Acklen’s office. “I have time, certainly,” he said.

“I grew up in an orphanage. Did you know that?”

“I read something about that, yes,” he replied.

“Well, when I was four years old, my father died of a heart attack. A complete shock to the family. And my mother, in his absence, had to find work to support our family. His parents had long since died and he had no siblings. My mother’s father was dead and her mother was in a state-run hospital. She also had no living brothers or sisters. She was, for the most part, entirely alone. She did her best to raise me and my older brother, but times were hard and she eventually felt that she could not take care of us. So she took us, without warning or explanation, to the Church of God Orphanage in Knoxville. I don’t know if you were aware, but a good number of children in orphanages at that time were not actual orphans. It was common for parents, fallen on hard times, to give up their children. In fact, there were several boys and girls at the orphanage who would be reunited with their parents and then, six months later, brought back to the orphanage when money had again run out. But that’s not entirely important, I suppose. I just thought you might be interested to hear it. The point was, Preston, that the traditional view of orphanages, especially at that time, was that they were depressing places where children were abused and neglected. And while that was quite true of some places, I have no doubt, my time at the orphanage was, frankly, a gift. My mother, bless her, had psychological problems, which were exacerbated by my father’s death. She hit us and put us through quite a bit of emotional abuse. She could not care for us. The orphanage could. I loved my time there, not least because I met my husband. I truly believed that each and every child in that home was my true brother and sister. I felt a kinship greater than any nuclear family. And while the staff was by no means a substitute for a mother and father, they treated me with kindness; I was loved, in some way, by not just two parents, but by a large group of people with whom I interacted daily. In fact, once I was old enough to leave the orphanage, Terry and I moved into an apartment while he started working at the store he would eventually own, and I felt so lonely in that place, removed from all my friends. I was completely out of sorts. And when we had our children, again I felt adrift, no one to help me or show me the best way to take care of these babies that had come into my life. And though we got through it, far better than most people, and we made a wonderful life for ourselves and our children and their children, I can’t help but think back on that time in the orphanage as the best years of my life. Isn’t that silly?”

“I don’t think so, Brenda,” Dr. Grind replied, feeling something click in his brain, his affection for Mrs. Acklen growing as she voiced something that he had considered for many years now.

“Well, it feels silly sometimes, but it’s true. And now, it seems like there are a large percentage of children who are unwanted and uncared for, drifting through this world, and I wish there was something in place for those children that’s better than what we have now. There are safety nets, but so many children slip right through them or they never even reach them. It seems to me that there must be a wider net, to make sure that every child is loved and cared for.”

“A network?” Dr. Grind offered.

“That’s too formal for my tastes,” she replied. “Not a network. Not even a community. Certainly not those awful communes that are just excuses for adults to remove themselves from society and do whatever they please, with no regard for the children. I’m talking about something quite different. Dr. Grind, excuse me, Preston, I’m talking about a family. I’m talking about a family that is larger than just a husband and a wife and their children. I’m talking about a place where everyone is connected and everyone cares for each other equally.”

“A family,” Dr. Grind then said, in agreement with Mrs. Acklen.

“A kind of family, yes,” she said, smiling. “A family that will not end, no matter what the circumstances. An everlasting family. An infinite family.” She reached across the desk and took hold of Dr. Grind’s hand, which he willingly allowed. “And I think, Preston, that you could help me make this happen. I think you are just the person I’ve been hoping for.”

Preston had no real idea as to what he could do to help Mrs. Acklen. In fact, what she was suggesting seemed too broad and unrealistic to ever be a reality, with no real structure for making something like this happen, at least in an organic way. But, as he held her hand, feeling the warmth of her skin and the easy way that it fit in his own hand, he could not resist her, could not deny her what she was asking for.

“Are you the person that I’m hoping for, Preston?” she asked.

“I think I might be, Brenda,” he finally said, smiling, so relieved that he thought he might cry.

Copyright (c) 2016 by Kevin Wilson. All rights reserved.  Kevin Wilson is the author of Tunneling to the Center of the Earth, a story collection, and one earlier novel, The Family Fang, which was recently released as a film starring Nicole Kidman and Jason Bateman. Wilson lives in Sewanee, Tennessee, with his wife, the poet Leigh Anne Couch, and their sons, Griff and Patch.

Kevin Wilson is the author of Tunneling to the Center of the Earth, a story collection, and one earlier novel, The Family Fang, which was recently released as a film starring Nicole Kidman and Jason Bateman. Wilson lives in Sewanee, Tennessee, with his wife, the poet Leigh Anne Couch, and their sons, Griff and Patch.