Desolation Rowboat

Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree teems with heartbreak, humor, and stunning prose

They say there are only two stories in literature: A stranger comes to town and a man goes on a journey.

Suttree — my favorite book, Cormac McCarthy’s masterpiece, an American Ulysses — is both. (And much more, but more on that later.) It’s the story of Cornelius Suttree, who shucks a life of family wealth and comfort in Knoxville to sink into its underworld, a place of “wild street preachers haranguing a lost world with a vigor unknown to the sane” and “flower ladies in their bonnets like cowled gnomes, driftwood hands composed in their apron laps and their underlips swollen with snuff.” He’s a stranger in his own town.

Suttree — my favorite book, Cormac McCarthy’s masterpiece, an American Ulysses — is both. (And much more, but more on that later.) It’s the story of Cornelius Suttree, who shucks a life of family wealth and comfort in Knoxville to sink into its underworld, a place of “wild street preachers haranguing a lost world with a vigor unknown to the sane” and “flower ladies in their bonnets like cowled gnomes, driftwood hands composed in their apron laps and their underlips swollen with snuff.” He’s a stranger in his own town.

His journey, like Leopold Bloom’s in Ulysses, is less epic than peripatetic. We see Suttree on the river, where he lives in a shantyboat and fishes from a skiff — the same river from which a suicide victim is plucked in the novel’s opening scene. We see Suttree in the squalid city, its drinking dens and dank alleys, along ruinous blocks peopled with poor souls even worse off than him: “An eyeless beggar addled with the cold sat in the empty feastday street singing a canticle to his eternal night and holding out a simple frozen claw for whatever might fall almswise.”

Suttree’s journey is also a descent, into his own “eternal night.” He’s a man of education and intelligence, of such promise once. What happened, Cornelius? Why? How? He’s grief-struck, tormented by his past: his stillborn twin brother, the wife he abandoned, and their young son who dies. He carries enough baggage for a season in Bloom’s Dublin, but Suttree covers very little ground, really. He mostly just goes sinking down, down…

And yet. Suttree is a rowdy book, filled with jinks high and low, outright hilarity, and hooch enough to float Sut’s shantyboat. There are characters named J-Bone, Worm, Boneyard, Oceanfrog, Hoghead, and Trippin Through The Dew. Ulysses, too. And there’s Suttree’s workhouse buddy (his mentee, really) Gene Harrogate, who with his strange predilections and inveterate scheming, is a one-man Coen Brothers comedy.

When Suttree is funny, it’s as funny as A Confederacy of Dunces.

Stanley Booth, the famed music writer who knows well life’s wild side from cavorting with blues singers and the Rolling Stones, called it “probably the funniest and most unbearably sad” of McCarthy’s books. This is why we read: to experience the sweep of existence. Rarely do we get so much of it in one volume. But that’s Suttree. It’s a lot, and then some. Set in the city where McCarthy was raised and said to be his most autobiographical novel, Suttree is violent and tender, wry and riotous, profane and playful. It’s an elegy and a meditation, a heathen prayer and a near-500-page howl.

Stanley Booth, the famed music writer who knows well life’s wild side from cavorting with blues singers and the Rolling Stones, called it “probably the funniest and most unbearably sad” of McCarthy’s books. This is why we read: to experience the sweep of existence. Rarely do we get so much of it in one volume. But that’s Suttree. It’s a lot, and then some. Set in the city where McCarthy was raised and said to be his most autobiographical novel, Suttree is violent and tender, wry and riotous, profane and playful. It’s an elegy and a meditation, a heathen prayer and a near-500-page howl.

It’s also the greatest collection of sentences this side of The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty. Here are a few:

“One rainy night nearby he heard news in his toothfillings, music softly.”

“He was looking out the window where nighthawks had come forth and swifts shied chittering over the river.”

“Suttree coming up out of this hot and funky netherworld attended by gospel music.”

And this one, from some play-by-play of a roadhouse brawl: “His busy freckled fists ferrying folks to sleep.”

The New York Times reviewed it twice, upon publication in 1979. Both quoted liberally from the book — the Cormac Effect. It’s like going to a Bob Dylan concert and he breaks into “Desolation Row.” You’re compelled to sing along.

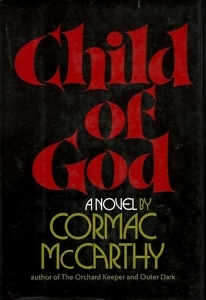

Not everyone does, mind you. Many scholars and serious readers of the man will tell you McCarthy’s best work can be found in his Western and Southwestern novels, as if in his Tennessee-set works — The Orchard Keeper (1965), Outer Dark (1968) and Child of God (1973) preceding Suttree — McCarthy still was finding his way out from under the spell of certain others.

Just last year in Oxford American, Christopher C. King wrote that McCarthy “discovered his voice” with 1985’s Blood Meridian — a galling thing for a Suttree-espousing Tennessean to have to read in the pages of “A Magazine of the South.”

Just last year in Oxford American, Christopher C. King wrote that McCarthy “discovered his voice” with 1985’s Blood Meridian — a galling thing for a Suttree-espousing Tennessean to have to read in the pages of “A Magazine of the South.”

Yes, I know Blood Meridian. A great book, beautifully written — and savagely so. But you can have it, for this exercise of identifying McCarthy’s masterwork. You can have that and The Border Trilogy and all the pretty horses they rode in on. You can have The Road and its post-apocalyptic hellscape — early 1950s Knoxville was as scary and more compelling.

I get it, though. McCarthy’s Tennessee novels are dark and gnarled, and small, I guess you would have to say. Insular, even. Because Tennessee isn’t vast and epic like the West, so McCarthy’s novels set here don’t have the weight and grandeur that Western novels gain just through geography (and gunplay). A yarn in Tennessee can take mythic proportions in the grand, vast West. Think of John Ford movies. Think of Patterson Hood of the Drive-By Truckers singing in his song “The Monument Valley”: It’s all about where you put the horizon / Said the great John Ford to the young man rising / Gotta frame it just right and have some luck, of course / It helps to have a tall man ridin’ on the horse.”

Suttree, meanwhile, is the story of a Knoxville river rat. It’s a yarn about a strayed son, a tortured soul, and a walking contradiction: He’s a loner, an outsider, that stranger in his own town, but a boon companion, not just liked but trusted. As Anatole Broyard wrote in The New York Times, “People trust Suttree because he does not want anything they’ve got, he does not compete.”

Suttree is singular. Suttree is Suttree, stubbornly so. Early on, an uncle visits the shantyboat. Trying to draw his nephew out of the life to which he’s sunk, the uncle suggests they’re “a lot alike.” Suttree snaps, “I’m like me. Dont tell me who I’m like.”

That might have been McCarthy himself talking to readers, other writers, critics, scholars, to anyone who would question his prerogative to write — or overwrite, as the familiar charge goes — as he chose. To anyone who would put him high on a shelf labeled “Southern Literature” but never fail to mention the William Faulkner influence, that second-hand pipe smoke the younger writer must be sucking in with every dense passage and dark turn. Derivative — that most damning word for a writer to have to hear. Another way of putting it: Tell me why you exist, exactly?

That might have been McCarthy himself talking to readers, other writers, critics, scholars, to anyone who would question his prerogative to write — or overwrite, as the familiar charge goes — as he chose. To anyone who would put him high on a shelf labeled “Southern Literature” but never fail to mention the William Faulkner influence, that second-hand pipe smoke the younger writer must be sucking in with every dense passage and dark turn. Derivative — that most damning word for a writer to have to hear. Another way of putting it: Tell me why you exist, exactly?

Maybe that’s why McCarthy looked west. Those wide-open spaces as far as one could see, blank pages on which to write those dipped-in-blood sentences of his. He could leave behind the comparisons to Faulkner, to Flannery O’Connor. He could leave behind everything.

Certainly it was, like someone said of Elvis dying, a good career move. He made his name and fame. The movies came calling. The Pulitzer Prize (and Oprah’s blessing) bestowed. McCarthy became a literary legend, if not a darling — he was too crusty, too uncompromising. The literary world didn’t coronate him so much as surrender. The terms were his. He’d won.

When McCarthy died in 2023 at age 89, The New York Times obituary by Dwight Garner sought to capture the storied man in full — although the Western books seemed to be given greater sway, while the early Tennessee novels were described as “bleak fables, set in the Appalachian South, related in tangled prose that owes an acknowledged debt to William Faulkner.”

McCarthy considered Faulkner an influence, yes. Of course he did. He said so in one of the early newspaper interviews that were rediscovered in 2022. He also mentioned James Joyce — and Leo Tolstoy, who may or may not have said that earlier bit about there being only two stories in literature. “Gutsy writers,” McCarthy called them.

But when McCarthy sat at the keys of his portable Olivetti (picked up for $50 from a Knoxville pawn shop about 1963 and used for 46 years, reportedly), what came out wasn’t the sum of his influences but something entirely new. It was pure McCarthy.

Similarities? Why, sure, in theme and execution and in other ways. He and Faulkner could both be notoriously difficult on the page — they’d drop you in kudzu to find your own way. Or not. But you wouldn’t mistake the writing of one for the other. On a pure sentence level, McCarthy would smoke Faulkner, even if Faulkner remains the greater writer. On a pure sentence level, McCarthy was doing something more than writing. It was performance.

Speaking of which: Pressed on his methods by Martha Byrd in the Kingsport Times-News in 1973, McCarthy said, “I can’t explain how one creates a novel. It’s like jazz. They create as they play, and maybe only those who can do it can understand it.”

Improvisation, then. A sort of conjuring. A master of the keys at work, a Thelonious Monk, let’s call him, of the written word.

So maybe Suttree isn’t McCarthy’s Ulysses or his attempt to give the citizens of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County some East Tennessee kin.

Maybe, in all its bold astonishments, it’s his Brilliant Corners.

David Wesley Williams is the author of the novels Everybody Knows (JackLeg Press, 2023) and Long Gone Daddies (John F. Blair, 2013). His short fiction has appeared in Oxford American, Kenyon Review Online, and in Akashic Books’ Memphis Noir. He lives in Memphis.