Bird Fever

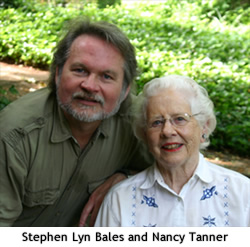

Stephen Lyn Bales explores a classic quest for the ivory-billed woodpecker

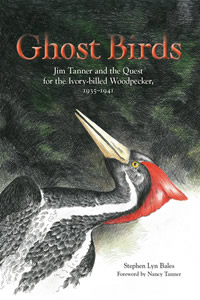

“Since the early 1900s, one question and one question alone has swirled around the largest woodpecker to live in our part of the world,” Knoxville naturalist Stephen Lyn Bales writes in his prologue to Ghost Birds: Jim Tanner and the Quest for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, 1935-1941. “Is it alive or dead? …. Ivory-bills have attained mythical status because they represent all that is wild and unobtainable and resilient in our natural world.” This fascinating book, focusing as it does on the history of the quest, fails to answer the key question, but it brings readers to the point where they feel qualified and energized to ask it.

Combining nature, biography, history, and mythos, Ghost Birds is concerned not only with rare birds but also with rare birders. Specifically, Bayles follows the course of a great but little-known American naturalist named Jim Tanner, who in 1935, at the age of twenty, set off on what would become one of the greatest cross-country bird-watching expeditions of all time. That trip, as well as a few that followed it, echoed in scope and dashing the wilderness travels of John James Audubon a century earlier. What Tanner, like Audubon before him, brought back from the swamps and forests—often trekking into places where Audubon himself had ventured—became a priceless addition to American natural history.

Tanner was the youngest of a three-man team financed by Cornell University, the American Museum of Natural History, and a wealthy bird enthusiast. Their express purpose was to venture far into the field to obtain the first motion pictures and sound recordings of rare American birds—and none was more rare than the ivory-billed woodpecker, which most scientists believed to be extinct by the 1930s. The group, led by Cornell ornithologist Arthur Allen (young Tanner was a last-minute addition), developed numerous specialized techniques and equipment still in use today, such as the first parabolic microphone—virtually identical to the ones networks now use to pick up chatter in a football huddle. They designed a truck that could drive into the woods and then raise a telescoping platform in order to film wild birds in their nests, despite the unwieldy size and weight of the day’s motion-picture cameras. The team’s combination of 1930s technical wizardry and determined leather-and-khaki bushwhacking turn a typically sedate subject into an expedition worthy of Indiana Jones—one with no crystal skull or golden statue at its end, but with an enormous red-crested bird that squawks like the bulb on a Duisenberg.

Tanner was the youngest of a three-man team financed by Cornell University, the American Museum of Natural History, and a wealthy bird enthusiast. Their express purpose was to venture far into the field to obtain the first motion pictures and sound recordings of rare American birds—and none was more rare than the ivory-billed woodpecker, which most scientists believed to be extinct by the 1930s. The group, led by Cornell ornithologist Arthur Allen (young Tanner was a last-minute addition), developed numerous specialized techniques and equipment still in use today, such as the first parabolic microphone—virtually identical to the ones networks now use to pick up chatter in a football huddle. They designed a truck that could drive into the woods and then raise a telescoping platform in order to film wild birds in their nests, despite the unwieldy size and weight of the day’s motion-picture cameras. The team’s combination of 1930s technical wizardry and determined leather-and-khaki bushwhacking turn a typically sedate subject into an expedition worthy of Indiana Jones—one with no crystal skull or golden statue at its end, but with an enormous red-crested bird that squawks like the bulb on a Duisenberg.

Naturalist Jonathan Rosen has described the ivory-bill as a bird “flying between the world of the living and the world of the dead, between the American wilderness and the modern wasteland, between faith and doubt, survival and extinction. No wonder the bird has taken on a sort of mystical character.” “And there the magnificent bird teeters,” Bales adds, “one zygodactyl foot in the here and now, the other in the hereafter. For more than one hundred years, the grave has been dug, but no one can confidently fill it in. Dressed in black, we stand around the gravesite with no final corpse to bury.”

Naturalist Jonathan Rosen has described the ivory-bill as a bird “flying between the world of the living and the world of the dead, between the American wilderness and the modern wasteland, between faith and doubt, survival and extinction. No wonder the bird has taken on a sort of mystical character.” “And there the magnificent bird teeters,” Bales adds, “one zygodactyl foot in the here and now, the other in the hereafter. For more than one hundred years, the grave has been dug, but no one can confidently fill it in. Dressed in black, we stand around the gravesite with no final corpse to bury.”

With such a mythical quarry, the quest cannot help but take on mythical aspects. There are mosquitoes, illness, and accidents, amid trackless swamps that stretch on for miles. In writing the book, Bales had the advantage of the rich journals Tanner kept through his travels, as well as the reminiscences of Tanner’s widow, Nancy, still living in Knoxville. The book is well illustrated with photographs from Tanner’s files, and filled with quotes from his copious journals. These have the effect of placing the reader directly in Tanner’s boots, holding a camera above a swamp thick with snakes, face to face with the greatest unknown of American natural history.

It’s enough to make you invest in a set of good binoculars and pair of thick wool socks.