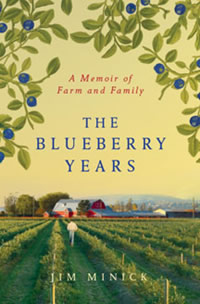

Of all the manifestations youthful idealism can take, perhaps the most earnest—and also the most apt to end in disappointment—is the one recorded so memorably by Henry David Thoreau. Walden; or, Life in the Woods was first published in 1854, and for the last 150 years it has inspired a certain kind of young person to obey Thoreau’s exhortation to “live deliberately.” Thoreau’s own life in the woods lasted two years. Jim Minick’s dream of being an organic blueberry farmer lasted a decade longer than that.

Minick grew up picking blueberries in his grandparents’ quarter-acre plot on a Pennsylvania farm that had been in the family since the early 1900s, but Minick and his wife Sarah didn’t arrive by a direct route at their own field of blueberries in the mountains of southwest Virginia. Before they even conceived of this homestead dream, they first had to get completely fed up with conventional life: “[W]e move,” Minick writes, “so that I can escape a job I hate, teaching high-school English in suburban Maryland.” By the time Jim earned a master’s degree in English at Radford University in 1991, the Minicks had decided they liked life in the mountains well enough to stay. Sarah taught kindergarten in rural Floyd County, and Jim stayed on at Radford as a writing instructor, and while happier than they were in the suburbs, they soon discovered that what they really wanted is more unstructured time—the kind of time schoolteachers have in summer but pay for with their very lifeblood the other ten months of the year.

Thus was born the idea of homesteading, of living life at a slower pace and in a deliberate manner that would be closer to Thoreau’s own dream and also, they hoped, give Jim more time to write and Sarah more time to knit and make baskets. When they found a ninety-acre farm that hadn’t been pastured or tilled in more than forty years, they overlooked its faults—the fields grown over in scrub pine, the falling-down outbuildings, the lack of a navigable road to the field: “We saw these things out of the sides of our eyes, only looking directly at what we wanted to,” Minick writes. In early 1992, when they signed the papers and moved into the hundred-year-old farmhouse on the property, the Minicks were still a long way from leaving their demanding day jobs for a rural idyll.

Thus was born the idea of homesteading, of living life at a slower pace and in a deliberate manner that would be closer to Thoreau’s own dream and also, they hoped, give Jim more time to write and Sarah more time to knit and make baskets. When they found a ninety-acre farm that hadn’t been pastured or tilled in more than forty years, they overlooked its faults—the fields grown over in scrub pine, the falling-down outbuildings, the lack of a navigable road to the field: “We saw these things out of the sides of our eyes, only looking directly at what we wanted to,” Minick writes. In early 1992, when they signed the papers and moved into the hundred-year-old farmhouse on the property, the Minicks were still a long way from leaving their demanding day jobs for a rural idyll.

Just how far away that dream truly was dawned on them only gradually, over a dozen years. Starting with a delivery driver who refused to take his eighteen-wheeler down the dirt-road final leg of the trip and so left a thousand blueberry bushes on the side of the road two miles short of the field, the Minicks hit every possible hurdle neophyte farmers can encounter. They felt isolated and lonely on the farm. The hives they set up near the blueberry field to aid in pollination soon sat empty after the bees swarmed. The old strawberry farmer next door scoffed at their plans to grow berries organically. They had problems with worms, weeds, weather. Marauding raccoons ate hundreds of pounds of berries. A copperhead bit Jim on the leg.

Despite these setbacks, the Minicks’ farm dream was not a failure. Through hard physical labor combined with careful research about the most effective organic practices, they created a field that produced three tons of berries in a five-week season during its first year of full maturity—delicious, perfect, healthy berries so uncontaminated by chemicals it was safe to eat them straight from the canes.

And there were customers, despite the isolation of the farm and its dirt-road access, for the Minick Berry Farm’s 1997 debut as a pick-your-own venture happened to coincide with the beginnings of a national food revolution. Terms like “organic,” “sustainable agriculture,” “CSA farms,” and “eat locally” were gaining currency, even in rural southwest Virginia, and the Minicks had faithful customers who would drive from miles—even states—away to gather their own certified-organic berries. The stories Minick includes about these regular customers are almost as fascinating as the Minicks’ own. Everyone feels Thoreau’s itch to self-sufficiency; even if they have only a morning to give to the gathering, that feeling of satisfaction is worth the drive. “It takes us a while to realize we’ve become prophets of a new religion,” Minick writes of his self-appointed acolytes. “We built a church, it seems, without intending, and now the rows fill up each day with worshipers, a congregation coming to take the sacrament, to eat the holy goodness of real food.”

And there were customers, despite the isolation of the farm and its dirt-road access, for the Minick Berry Farm’s 1997 debut as a pick-your-own venture happened to coincide with the beginnings of a national food revolution. Terms like “organic,” “sustainable agriculture,” “CSA farms,” and “eat locally” were gaining currency, even in rural southwest Virginia, and the Minicks had faithful customers who would drive from miles—even states—away to gather their own certified-organic berries. The stories Minick includes about these regular customers are almost as fascinating as the Minicks’ own. Everyone feels Thoreau’s itch to self-sufficiency; even if they have only a morning to give to the gathering, that feeling of satisfaction is worth the drive. “It takes us a while to realize we’ve become prophets of a new religion,” Minick writes of his self-appointed acolytes. “We built a church, it seems, without intending, and now the rows fill up each day with worshipers, a congregation coming to take the sacrament, to eat the holy goodness of real food.”

Interspersed among the chapters devoted to his own story, Minick includes chapters—much like the cetology sections of Moby-Dick—designed not to advance the narrative but to provide actual information. These “Blue Interludes” range from explanations of organic farming practices to brief biographies of the botanists who first cultivated blueberries to data on the failure rate of family farms to the history of blueberries in story and film and song. Aside from simply being interesting in their own right, these chapters ground the Minicks’ experience in both science and culture. Fans of Michael Pollan ought to flock to this book, too.

Ultimately, however, this is not one of those heartwarming, we-made-it-against-all-odds stories. It’s clear from the very beginning of The Blueberry Years that Jim and Sarah Minick are no longer blueberry farmers. In spite of their own backbreaking (and knee-destroying and scar-bestowing) work, in spite of their customers’ loyalty, and in spite of the copious amounts of blueberries they grew, the Minick Berry Farm never turned a profit. Harder for Jim and Sarah to bear, it didn’t provide the hoped-for time to write poems and make baskets, either. It did, however, provide the fertile ground for this good book, and that’s a bounty in its own right.

July 5, 2012, update: Jim Minick will discuss The Blueberry Years at 6 p.m. on July 20 at Union Ave. Books in Knoxville.

Tagged: Nonfiction