Unstoppable

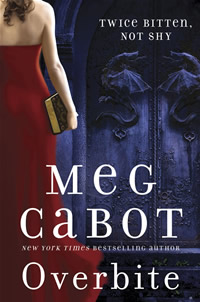

Meg Cabot is famous for The Princess Diaries and other YA titles, but a new series for adults is the next big thing for this publishing juggernaut

Meg Cabot may be the hardest working woman in the book business. To date, she has published more than fifty novels (for teens, pre-teens, and adults) and shows no sign of slowing down. Her books beget sequels, spinoffs, and both Hollywood and made-for-TV movies. She blogs. She tweets. She maintains a dauntingly thorough website, where she welcomes readers into her personal life and behind the scenes of her novels. (Pictures of various real-life locations, as well as of the dog that inspired Jack Bauer, the canine scene-stealer in the Meena Harper series, can be found here.)

Cabot is probably best known for her Princess Diaries series, which launched in 2000. The novels feature the goofy and endearing Mia Thermopolis, an ordinary high-school student who suddenly discovers she’s heiress to the throne of Genovia, a small European country. The wildly popular (and absolutely charming) books became two movies, each starring Anne Hathaway as Mia and Julie Andrews as her formidable grandmother. Cabot could easily have rested on her laurels; instead, she kept writing and publishing at a breakneck pace. More serial novels for young adults, a series for tweens, and several books aimed at adult readers followed in stunning succession.

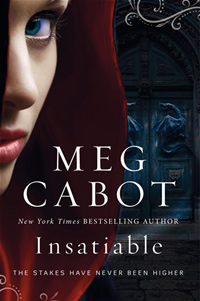

Her latest series, this one for adults, follows the adventures of Meena Harper, a soap-opera writer and vampire hunter torn between the devastatingly attractive Lucien Antonescu—son of Dracula himself—and Antonescu’s sworn enemy, the vampire hunter Alaric Wulf. Like all of Cabot’s books, Insatiable and Overbite are pitch-perfect: frothily addictive, glamorous but also down to earth, and grounded in solid research. (Meena Harper, for instance, was inspired by the character Mina Harker, who appears in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.)

Her latest series, this one for adults, follows the adventures of Meena Harper, a soap-opera writer and vampire hunter torn between the devastatingly attractive Lucien Antonescu—son of Dracula himself—and Antonescu’s sworn enemy, the vampire hunter Alaric Wulf. Like all of Cabot’s books, Insatiable and Overbite are pitch-perfect: frothily addictive, glamorous but also down to earth, and grounded in solid research. (Meena Harper, for instance, was inspired by the character Mina Harker, who appears in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.)

Though Cabot may seem to be cashing in on the recent teen-vampire craze, she’s no stranger to supernatural topics: both the 1-800-WHERE-U series and the Mediator series were paranormal before paranormal was cool. “I had a hard time at first getting those books published,” Cabot told CNN earlier this year. The subsequent explosion of paranormal books is, Cabot feels, altogether positive: “To have [a supernatural book] with relatable female characters was unusual, so it’s really great how now there are so many,” she says simply. And there will be more to come—Overbite will be released on July 5, and Cabot is already working on subsequent volumes.

Chapter 16 caught up with Cabot by email prior to her appearance July 7 at the Nashville Public Library.

Chapter 16: You are stunningly prolific, with new books coming out this summer (Overbite), next spring (Abandon), and several more in the works. How do you get all this done? Can you describe a typical writing day?

Meg Cabot: I actually have so many people who help me on an almost daily basis—from publicists to personal assistants to a housekeeper who also cat-sits to, of course, my fabulous husband who does all the cooking; he supported me while I was trying to get published, and then, once that happened, I agreed to support him, especially after he went to culinary school—which makes my accomplishments much less impressive. I just do one thing: write books. I don’t even have kids. Just two horribly behaved cats. So that makes it much easier to write from ten to five. On the days that actually happens, which is less and less often, lately.

Chapter 16: One of the greatest joys for a bookish child is reading all the way through a series—falling in love with a set of characters and a storyline and then following it through a stack of books. (At one point, I was forbidden by my own parents to reread the Little House books unless I read something—anything—between the books.) You’re such a wonderful serial novelist that I can’t help but wonder: which were the series books that you loved growing up?

Cabot: I grew up in a college town (Bloomington, Indiana)—which got me in trouble as a kid since I wanted to read nothing but what some people considered “junk”—Spiderman and Star Wars comic books, Anne McCaffrey sci-fi and fantasy novels (and also Nancy Drew and romance novels, of course). But I was also quite lucky because I lived in the same neighborhood as (and babysat for) English and Women’s Studies distinguished professor Susan Gubar, who introduced me to Louisa May Alcott’s “smutty” books (the ones she wrote pre-Little Women) in addition to her own feminist text (along with Sandra M. Gilbert), The Madwoman in the Attic, which led me toward many “classics” that I adored (Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte) in addition to my beloved “junk.”

I still don’t think anyone should be “forced” to read certain books just because other people perceive them as “classics” and other books as “junk.” Some people’s “junk” is another person’s “classic” or “comfort” reads. Sometimes these books are a way for children (or adults) to cope with stress, or even work out the mechanics of storytelling to become authors themselves.

I still don’t think anyone should be “forced” to read certain books just because other people perceive them as “classics” and other books as “junk.” Some people’s “junk” is another person’s “classic” or “comfort” reads. Sometimes these books are a way for children (or adults) to cope with stress, or even work out the mechanics of storytelling to become authors themselves.

Chapter 16: This is a silly question, perhaps, but I’ve always wondered how a series writer knows when to stop? Do you plan the trajectory beforehand, or do you just keep going until you sense the narrative has come to a satisfying end? I can think of many girls who’d be thrilled to follow Mia Thermopolis all the way through her dotage.

Cabot: I do have a final destination in mind, and usually know exactly how many books it will take to get there. I think it’s because I’ve been writing stories for so long—it’s kind of like how basketball players know the exact play to make in the heat of the moment. I knew it would take sixteen books to get Princess Mia through freshman year of high school to her graduation … and it did.

I like to say storytelling is like going on a trip: you always know from the beginning where you want to end up (but, of course, you never reveal this to the reader until the last page). The fun is experiencing what’s going to happen along the way. (Which is why I don’t work from an outline, but why I often get “way laid” by wrong turns. This is called writer’s block.)

Chapter 16: Many of your plots draw on myths and legends—I’m thinking of the Avalon High books, which tweak the King Arthur story, and your present vampire series. Do you research the subjects extensively before you begin writing? Or do you begin with the same vague ideas most of us have about, say, the various vampire stories we’ve heard or read, and then refine the details as you write?

Cabot: I do extensive research because I want my books to have a great deal of authenticity, for the plots to be as believable as the characters. One of the reasons people fell for Meena Harper from Insatiable was that she was a highly relatable character in a plot that, while it could have strained [credulity], was actually highly researched, down to the buildings in which the characters lived, to the fact that the vampires she doesn’t believe in are descended from a real person … Vlad the Impaler, a historic figure who actually lived in the 1400s and is one of the most feared military leaders of all time. I did read dissertations about Vlad, researched his family and residences, and tried to make the story about his sons, wives, and life as close as possible to what really happened to him. For Overbite, I spent hours on NYC’s Parks and Rec website, in addition to many others related to a certain underground stream. Why? You’ll see!

Chapter 16: A lot of book-loving adults are mortally afraid that technology is turning children into passive consumers of trivia and gossip, uninterested in (and unable to concentrate on) books. Leaving aside the question of whether kids still read (obviously they do, as your sales clearly indicate), I’d like to ask whether you agree with these parental fears. It seems that the opposite could be argued, too: that the Internet has in fact turned kids who read into kids who write (or at least who blog).

Cabot: I do believe the opposite is true. Technology has just increased the many ways and formats in which we are experiencing story. What should be changing is our definition of what a book is. I’ve seen “apps” that are dozens of pages long, but because they’re only available to be read on an iPad or a cell phone, they aren’t considered “a book.” Why? This seems as wrong to me as the fact that Prince Valiant was one of my favorite “books” growing up, but because it was a comic strip—featuring murder, gripping love stories, animal abuse (and rescue), jousting, history, you name it, that went on weekly for half a century—no one counted it as a book, or even reading, either. Again, why? It used to make me so mad.

Now there are video games where, just to understand what’s going on with the characters in the game, there is a ton of backstory that has to be read on screen. (I know numerous “book” writers who have been hired to write actual text that appears on the screen—book length chapters.) This may not count as reading to some parents, but it certainly does to me. I’m not saying I should have been allowed to write a “book report” about Prince Valiant, but I could have—just as many boys who today are being accused of “not reading” could write book reports on their favorite video games.

Now there are video games where, just to understand what’s going on with the characters in the game, there is a ton of backstory that has to be read on screen. (I know numerous “book” writers who have been hired to write actual text that appears on the screen—book length chapters.) This may not count as reading to some parents, but it certainly does to me. I’m not saying I should have been allowed to write a “book report” about Prince Valiant, but I could have—just as many boys who today are being accused of “not reading” could write book reports on their favorite video games.

All reading—on screen, off screen—counts.

Chapter 16: You’re a blogger yourself. Do you recommend blogging as a way for would-be writers to dip their toes in the water? Or is blogging something entirely different from novel writing?

Meg Cabot: Certainly there are many books that have been told in diary format, as I should know. And I’ve read numerous books by bloggers who’ve gotten publishing deals based on their blogs. But while I love my blog, I generally save my “best” stories for my books, not my blog. Why? Because my family doesn’t take too kindly to me blogging about them. They would like to remain anonymous, so I just write about them in my books, but change their names and give them glasses so they don’t recognize themselves.

Chapter 16: You note on your website that you found an agent only after three years of constant querying. How did you keep your spirits up during those long years?

Meg Cabot: Nachos. No, seriously. A big plate of nachos makes everything better (also beer, but I don’t recommend that for my readers who are under twenty-one). Eventually I had to cut back on both the nachos and beer, though, because it was taking a toll on my weight.

That’s when my husband stepped in. He was great. Every day when I got a rejection letter (and I did, every day, except Sunday when there was no mail), he’d say, “Do you like to write? Yes? Then keep doing it. Who cares what other people say? Besides, this is cheaper than a Lottery ticket, and you have a better chance at winning.” So, that kept me going. Especially when it turned out to be true.

Chapter 16: How is writing for teens and tweens different from writing for adults? Is it simply a matter of the main characters’ ages and activities (for the grown-ups, more sex, less slang, fewer pimples, jobs instead of school, no parents … ) or do you consciously change your mindset and try to alter your style based on your target audience?

Meg Cabot: I was really into acting as a teen, and I think it’s a lot like that: as a writer, just like as an actress, you try to get into the character. I don’t have curse words or kissing in my Allie Finkle’s Rules for Girls series (it’s targeted for middle grade readers) because at that age I wasn’t allowed to curse or kiss anyone (yucky)! My books for teens don’t have curse words (beyond pretty mild stuff) for the same reason: my dad would have killed me if he caught me cursing back then.

With my adult books, I try to think how I’d feel if I, as a career girl in Manhattan, ran into a hot vampire—then a hot demon hunter showed up, wanting to kill us both. I’d probably swear—but not too much, out of respect to my dad.

Meg Cabot will discuss Overbite at the Nashville Public Library on July 7 at 6:15 p.m. as part of the Salon@615 series. The event—a reception, reading, and book-signing—is free and open to the public. Books will be available for sale.