Fearless and Exacting

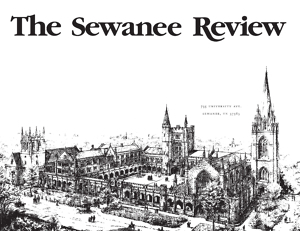

The new Sewanee Review will appear the end of this month, and “new” hardly begins to describe it

Eleven months ago, Adam Ross was named The Sewanee Review’s first new editor in nearly forever, and the storied journal is scheduled for its long-awaited rebirth at the end of this month. It’s a short gestation by Rossian standards—his novel, the much-lauded Mr. Peanut, was thirteen years in the making. But the result is still a monumental makeover.

The changes begin with the shock of art on the front of a magazine that has never printed anything other than text on the cover, and they continue throughout the volume. Women’s voices abound. There are writers of color, including one whose narrator uses the n-word three times in his first two sentences. There are unknown writers appearing next to lesser-knowns next to hotshots and stars. There is a potent poem whose lines are journalism extracts arranged in a cascade of boxes. And there is perhaps enough transgression to satisfy the spirit of Tennessee Williams, whose bequest to the University of the South supports the Review’s publication.

The changes begin with the shock of art on the front of a magazine that has never printed anything other than text on the cover, and they continue throughout the volume. Women’s voices abound. There are writers of color, including one whose narrator uses the n-word three times in his first two sentences. There are unknown writers appearing next to lesser-knowns next to hotshots and stars. There is a potent poem whose lines are journalism extracts arranged in a cascade of boxes. And there is perhaps enough transgression to satisfy the spirit of Tennessee Williams, whose bequest to the University of the South supports the Review’s publication.

Ross has, in short, imposed modernity on the nation’s oldest continuously published literary quarterly. In conversation, he seems duly awed by the legacy, where so many literary greats—Flannery O’Connor, Cormac McCarthy, T.S. Eliot, Robert Penn Warren, Saul Bellow, Sylvia Plath, and Eudora Welty—have been published. But he’s also adamant that the journal cannot keep trading on its past. “The hazy desire for former times,” Ross writes in his debut editorial, “is the enemy of present-day truth—especially now, following the election of a president whose campaign not only revealed enduring, deep-seated rifts in our nation but also the destructive powers of nostalgia.”

Prior to the launch of Sewanee Review’s redesign on January 31, Ross answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: George Core, your predecessor, started as Sewanee Review editor during the Nixon years, about the time you entered grade school. Can you imagine having such a long tenure? Do editors, like politicians, need term limits?

Adam Ross: No, I can’t imagine doing this at ninety-two, though the length of Mr. Core’s tenure makes him an outlier so far as the magazine’s history goes. Most Review editors last about a decade. On the other hand, it’s such a fantastic job, given whom I’ve been able to work with. Consider some of the writers appearing in our first issues: Jon Meacham, Alice McDermott, Lauren Groff, Hannah Pittard, Tom Franklin, and Stephanie Danler. We redesigned the magazine with Knopf’s legendary Peter Mendelsund. My staff are four topflight recent University of the South grads drunk on literature. I could see myself doing this until retirement, whenever that is.

So I don’t know about term limits. What’s clear to me is that to be successful you need to maintain a radical openness to the work that comes across your desk. And you need to be willing to step down once you’ve lost that receptivity, that capacity for surprise.

Chapter 16: “Venerable” is a commonly used adjective for The Sewanee Review. Are there less flattering descriptions that hold at least a kernel of truth?

Chapter 16: “Venerable” is a commonly used adjective for The Sewanee Review. Are there less flattering descriptions that hold at least a kernel of truth?

Ross: “Irrelevant.” Too few people read the Review. There’s a reason for that. I think the quarterly drifted from participating in the broader literary conversation. That’s neither a dig on its quality nor a criticism of the conversation it was having—great writers in every genre and discipline have always filled its pages. George Core published poets like Christian Wiman, Seamus Heaney, Wendell Berry, and Howard Nemerov. But the magazine’s bandwidth got a little narrow, I think.

America’s literary landscape is more polyphonic than ever. You have to keep your ear to the ground, be on the lookout, get off the mountain. You also have to be willing to be in conversation with many different writers about their interests because then you can conjure content together.

Chapter 16: Did you ever try to get published in The Sewanee Review?

Ross: I submitted something in the early ‘90s, just out of grad school, and got a form-letter rejection. I was furious and vowed I’d one day take over as the editor. All has gone according to plan.

Chapter 16: What did you do to get the job?

Ross: It was unquestionably the most intense vetting process I’ve ever experienced, one that lasted nearly four months. In fall 2015, I was working on my novel when I got a call from The American Scholar’s Robert Wilson. He’s a Sewanee alum, based in D.C., and was on the university’s national search committee. This led to an interview in Nashville with University Provost John Swallow, followed by my submitting a mission statement and extensive proposals for future issues. Then came two days of interviews at Sewanee. I talked to so many people about so much it was like having an entire book tour compressed into forty-eight hours. Each stage of the process made me more excited about the position. It was once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Chapter 16: What’s your funniest anecdote about the place?

Ross: John Jeremiah Sullivan, one of the most important and original nonfiction writers in America today (also a Sewanee grad), agreed, in February, to write a piece for our first issue about the first blues song. I was thrilled. I’m a huge fan of his, and his writing in this area is groundbreaking.

However, every editor who’d worked with him warned me that he was terrible at making deadlines. So I gave him a deadline two months in advance of press time. Which he blew. I gave him another a month, and he missed that one as well. “The piece is almost there,” he texted me. “Working in twelve-hour shifts. You will have pages soon (really).” He’d miss another deadline and write: “Today’s the day.” It wasn’t. “The piece has attained solidity,” he assured me. “You will have it tomorrow.” Nope.

Finally he agreed to fly down from New York and basically turn himself in to the authorities. He’d just attended the Whiting Awards ceremony—his book in progress received a big grant—and I locked him in a cabin deep in the Monteagle woods—I’m not kidding—where he stayed for a couple of days. Then he made a jailbreak and returned to New York. He did deliver the piece, and it’s miraculous. But the stress of waiting for it nearly killed me.

Chapter 16: Can you give me another taste of your first issue?

Ross: One of my favorite pieces is poet Mary Jo Salter’s essay on the late Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Mark Strand. It’s about how great artists corner a certain niche of existence and make it uniquely their own—how painter Edward Hopper Hopperizes the world, for instance, or Mark Strand Strands you.

Chapter 16: How do you see yourself pivoting from fiction writer to editor?

Ross: Well, I’ve learned a lot from my editor, Knopf’s Gary Fisketjon. There’s no one better in the business, and I’ve emulated his approach on every page of the Review, which is to give each piece the closest reading possible. “A writer makes a million choices,” Gary likes to say, “and I try to eliminate the several thousand wrong ones.” But this also isn’t my first rodeo. The job is not unlike the work I did as special-projects editor for the Nashville Scene. I had a stable of great writers, we had themed issues, I got to know their work, we brainstormed content together, and then I turned them loose on the world.

Just as there are actors’ directors, there are writers’ editors. William Maxwell wore both hats. Toni Morrison was an editor at Random House. Jonathan Galassi at FSG comes to mind. Because I’ve written fiction and nonfiction, I intimately understand the struggle writers face. They want dialogue. They appreciate it when you see their work from the inside out, especially at the draft stage, which is what I’m trying to do—understand their intention when they might not yet completely—before the process of burnishing it on a line-by-line basis begins.

I’ll admit that editing is a lot easier than writing your own stuff. And it’s supremely satisfying to introduce our debut fiction writers to the world—Sidik Fofana and John Sesgo. The joy I felt editing their work reached stratospheric levels.

Chapter 16: Who have SR’s readers been? Do you see that changing?

Chapter 16: Who have SR’s readers been? Do you see that changing?

Ross: Recently, most were contributors and past contributors. Several of them will still be writing for us. But new voices will predominate, and they will bring an entirely new and hopefully larger audience to the quarterly. All but one of our first issue’s writers are enjoying their Sewanee Review debut. And I’m proud to say that this is the first issue in the quarterly’s history in which more than half its writers are women. It wasn’t even close before.

Chapter 16: SR’s editors, since its founding in 1892, have all been white men. Talk about diversity and what the lack of it portends.

Ross: No doubt we have all been white, but let me state this for the record: Andrew Lytle, Monroe K. Spears, and George Core were all remarkable editors of the Review. Consider that in Allen Tate’s first issue, in 1944, you had Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, Katherine Anne Porter, and W.H. Auden, among others. His roster reflected the literary community of the time, and I’m tasked with the same challenge.

So I’d shift the question’s emphasis. If its implication is that white men will only publish white men, well, I disagree. Lorin Stein, The Paris Review’s editor, doesn’t struggle to publish a magazine that reflects America’s diverse landscape. Nor does the The New Yorker’s David Remnick or The Kenyon Review’s David Lynn. John Freeman’s biannual journal Freeman’s, is amazing. Look, diversity for the sake of diversity isn’t an editorial vision. However, a view toward excellence can lead to diversity, so long as you cast a wide net, and I’m committed to that.

I’d also add that, so far as the previous SR editors go, I’m an outside-the-box hire. I’m neither an academic nor a Southerner. I’m American, New York born, whose mother’s family, the Thayers, came over on the Mayflower and founded West Point, while my father’s family were Hungarian and Russian immigrants. I’m a true-blue mutt.

Chapter 16: You’ve lived in Nashville for over two decades. What do you mean you’re not a Southerner?

Ross: You can take the boy out of New York City but not New York City out of the boy. Manhattan’s hustle and bustle will always affect the way in which I interact with people, and it makes me something of an outlier here. Yes, when my parents talk at the dinner table my wife thinks we’re arguing. I drive too fast and tend to lean on my horn. (It would be really nice if people here learned right of way.) I am by nurture and region direct, which down here can seem blunt to the point of rudeness. At the same time, there’s a humaneness about Nashville that I cherish and would hate to see change. As Sheryl Crow recently said in a television interview, “Nashville’s great. Please don’t move there.”

Chapter 16: What must endure about The Sewanee Review?

Ross: It has always been committed to excellent writing. We have to remain fearless and exacting about that. That’s why its reputation is deserved. You don’t continuously publish since 1892 by being average.

Chapter 16: I’m currently trying to read a novel by a famous contemporary author and find myself thinking, “No one would publish or read this, if not for the author’s fame.” Ever have that experience?

Ross: Of course. I’ll add that this novelist and short-story writer is very aware of how hard it is to write a decent book, let alone a really good one. Great books are rarer than anyone likes to admit.

Chapter 16: So are you considering a blind-submission policy?

Ross: I don’t feel any need for it. I want the majority of our submissions to be from new writers.

Chapter 16: What’s the best book you’ve read recently?

Ross: That’s a tough question. It’s been an excellent reading year. Everyone should read Colson Whitehead’s National Book Award winner, The Underground Railroad. At its best, it restores what I’d call the “awful wonder” of slavery, by which I mean that, reading it, you experience the institution’s horror as well as the amazement that our nation actually did something as morally perverse as that. But the best books? I’ll suggest three: Megan Abbott’s You Will Know Me, Ian McGuire’s The North Water, and Chris Bachelder’s Abbott Awaits.

Chapter 16: What’s the status of your novel-in-progress, Playworld? What are your future plans besides being SR’s editor?

Ross: My future plans are to finish my novel. I’m close to halfway through, I like what I have, and I’d love to be done sooner, but, man, I’ve been busy.

[To read The Sewanee Review online (after January 31), click here. To read a profile of Adam Ross in connection with his editorship of the journal, click here.]

Brooks Egerton, a writer and editor, grew up in Nashville and now lives in Sewanee.

Brooks Egerton, a writer and editor, grew up in Nashville and now lives in Sewanee.