The Widower of the South

In A Separate Country, Robert Hicks takes a turn around war-scarred New Orleans with the Confederate general who searched for redemption there

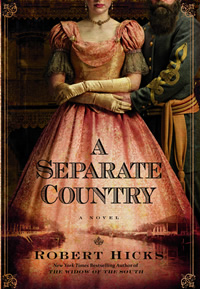

Robert Hicks dreams big. In A Separate Country, his new novel, he’s re-imagined in 400- plus pages the life and last days of the mythic John Bell Hood, former general of the Confederate States of America. This sort of endeavor is only natural for a man whose first novel was The New York Times bestseller The Widow of the South and who is now leader of Franklin’s Charge: A Vision and Campaign for the Preservation of Historic Open Space. Hicks has never shied from the big task, whether fighting the Herculean sprawl of Williamson County or imagining the thoughts of a legendary figure of the past.

Set in New Orleans in August of 1879, A Separate Country is told through a fictional memoir left behind by a dying Hood, the confidential diary of his wife Anna Marie, and the notes of Eli Griffin, a young man who first appeared in The Widow of the South and who is now charged with the manuscripts’ care following their owners’ deaths. As a general, Hicks writes, John Hood was an “arrogant” and “brutal commander” with little “patience for weakness.” His time on the battlefield turned him into a legend: after Gettysburg, his left arm hung slack and useless at his side, and a wooden leg replaced his right one following the Battle of Chickamauga. He was the “Gallant Hood,” a man who “led as if battle was a bracing bit of exercise, a game.”

Set in New Orleans in August of 1879, A Separate Country is told through a fictional memoir left behind by a dying Hood, the confidential diary of his wife Anna Marie, and the notes of Eli Griffin, a young man who first appeared in The Widow of the South and who is now charged with the manuscripts’ care following their owners’ deaths. As a general, Hicks writes, John Hood was an “arrogant” and “brutal commander” with little “patience for weakness.” His time on the battlefield turned him into a legend: after Gettysburg, his left arm hung slack and useless at his side, and a wooden leg replaced his right one following the Battle of Chickamauga. He was the “Gallant Hood,” a man who “led as if battle was a bracing bit of exercise, a game.”

The historical Hood did publish a post-war memoir, Advance and Retreat. Though Hicks mentions the book in A Separate Country, the novel introduces a confidential second memoir, the “real” story of John Bell Hood. In this “record of a man finished with war,” the fictional Hood views the past not as a glorious testimony of his battlefield exploits, but as an affliction to be endured. He is filled with guilt, endlessly brooding, and obsessed that he may have “cost many men their lives without good reason.” In his notes he writes, “I have spent years searching through papers, letters, journals and maps, looking for proof that I had not alone ruined the Army of Tennessee and led thousands of boys off to needless slaughter at Franklin and Nashville.”

Hood’s celebrated heroics have come at a price. He believes “a man changes when he’s killed someone” because “so much of what was possible for him in life becomes impossible: innocence, grace, forgiveness, sweetness.” The challenge is to “set out to become a man again … a human.” For Hood, the way to recovered humanity is through Anna Marie, “the light that went with my darkness.” Independent and strong-willed, Anna Marie bears eleven children before her death in the months before Hood’s, and her diary is written as a letter to her eldest daughter, Lydia. “There are things I must explain to you,” she writes. “You should know how we have become who we are.”

“I have spent years searching through papers, letters, journals and maps, looking for proof that I had not alone ruined the Army of Tennessee and led thousands of boys off to needless slaughter at Franklin and Nashville.”

In A Separate Country, the past is never past. As a dramatic rendering of individuals seeking transformation (the word “change” appears again and again and again throughout the book), the novel indicates that Hicks’s aspirations are nothing less than Faulknerian. Eli Griffin says of Hood’s memoir, “It’s about the time after the war. About New Orleans. About him and Anna Marie. And disease and killing and penance and salvation and love and every other damned thing you wouldn’t think he’d ever thought, let alone write down.”

A Separate Country is dedicated to New Orleans. In her diary, Anna Marie tells her daughter, “I hope you will love it as I have, imperfectly, inconstantly, but passionately. I am captured by this town of my ancestors, by the heat and milky bright light.” Hicks must feel the same way, given the number of paragraphs he devotes to describing the city. His lush prose turns New Orleans from mere setting into a character as real as any other on the page. It is a city of “fat men in vests trading cotton and rice straight from the quay. The horses in their stalls at the fairgrounds. Smoke on the streetcar, watermelon cast into the water of the St. John by playful boatmen. Drunk men, men with monkeys, men without shoes, men without sense, men in tall hats and thick beards. Mandolins on the galleries.”

No wonder reviewer Charlotte Hayes noted in The Washington Post, “Anyone who has ever lived in New Orleans must be prepared to be made homesick.” Hicks writes of mysticism and Catholicism, an ethnic stew of Irish, Spanish, Creoles, Germans, English, américain, and blacks together in a city where the wonder and weirdness is rendered in 3-D color and full stereo sound. The reader smells “the perfume off the whores who rustled by, hears the “sound of the wharf creaking under the weight of the men and horses and the pounding of the barges and steamers tied too loose on their moorings,” sees the packet boats “lugging great piles of oranges and green bananas and bales of plantation cotton” and feels the “clouds of mosquitoes mov[ing] together like whining ghosts between the piles of boxes and cotton and vegetables.”

The writing here is fluid, each sentence carefully crafted. Hicks is thoroughly invested in creating a post-Civil War world that is whole and complete. But the book’s merits are also its greatest weakness. Gorgeous language at times descends into florid prose and frustratingly repetitive detail. This is high drama, a Civil War romance, and the genre demands a little sex thrown in with historical fact, but must Hood fall prey to cliché and be “ravenous” for Anna Marie? The South is known for its eccentrics, but the parade of archetypes here borders on stereotype: There’s a dwarf and an octoroon, brothels and convents, riverboats and wharfs, magnolias and wailing women in white, drum beats, dark swamps and wild nature. This is Southern Gothic on speed.

The writing here is fluid, each sentence carefully crafted. Hicks is thoroughly invested in creating a post-Civil War world that is whole and complete. But the book’s merits are also its greatest weakness. Gorgeous language at times descends into florid prose and frustratingly repetitive detail. This is high drama, a Civil War romance, and the genre demands a little sex thrown in with historical fact, but must Hood fall prey to cliché and be “ravenous” for Anna Marie? The South is known for its eccentrics, but the parade of archetypes here borders on stereotype: There’s a dwarf and an octoroon, brothels and convents, riverboats and wharfs, magnolias and wailing women in white, drum beats, dark swamps and wild nature. This is Southern Gothic on speed.

A Separate Country dreams big, just as its creator does. Its high aspirations mean it sometimes struggles, but a patient reader will be rewarded. This is, after all, the slow-moving South of over a hundred years ago. A “delicate labyrinth of courtyards and hidden gardens,” New Orleans is a mystery to Hood. He is a man of secrets living in a city full of them, and the novel Hicks presents of Hood and his wife may be long and winding, often contradictory, but it’s a vital, living-and-breathing portrait of a man, a woman, and their marriage. By imagining their story, Hicks is exploring the eternal questions: What does it mean to be human, and what courage does it take to become whole?