The Chains of Love

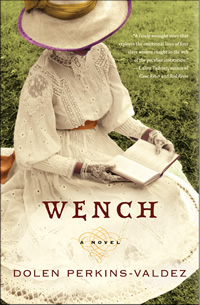

In her deeply original debut novel, Dolen Perkins-Valdez looks at the interior lives of the enslaved women kept as mistresses by Southern planters

Wench, a story of enslaved concubines and their white male masters, is a surefooted and engrossing work of historical fiction. While debut novelist Dolen Perkins-Valdez, a Memphis native, grounds her story in compelling nineteenth-century research, the book finds its center and momentum not in reams of facts but in one woman’s impossibly conflicted heart. Deeply interior and elegantly written, this novel reveals shades of emotional complexity in the slave-owner relationship, one often portrayed as a classic battle of good and evil, heroes and villains.

Wench focuses on a young enslaved woman named Lizzie, who each summer accompanies her master, Nathaniel Drayle, from Tennessee to Tawawa House resort in the free state of Ohio. This resort was the real-life inspiration for Perkins-Valdez: In the mid-nineteenth century, Tawawa was a popular escape for wealthy white Northerners and Southerners alike. Southern plantation owners often brought entourages of slaves with them, a practice many Northern guests frowned upon, and which is believed to have contributed to the resort’s decline in popularity and, ultimately, its shuttering in 1855. Building on this largely unknown bit of history, Perkins-Valdez imagines the close friendship of Lizzie and three other slave women she meets at Tawawa: Reenie, Sweet, and the newest to the fold, Mawu. All are mistresses to their owners, whose wives do not accompany them to Tawawa.

Lizzie is fascinated by red-haired, brash-talking Mawu. “There was something different about this one,” Lizzie thinks. “As if something bubbled beneath her surface just like the flesh simmering beneath the thick soup in the iron pot beside them.” Mawu wastes no time in pressuring the other women to join her in escaping. (“Us is here in free territory and ain’t nobody thinking about making a run for it?” she taunts.) Meanwhile, they meet a white Quaker woman named Glory, who seems likely to help maneuver a getaway. The question of whether to stay or go is an easy one for Mawu, whose master is a cruel man. It is less so for the other women, especially Lizzie, who is genuinely fond of Drayle and can’t bear the thought of abandoning the two young children she has by him.

Lizzie is fascinated by red-haired, brash-talking Mawu. “There was something different about this one,” Lizzie thinks. “As if something bubbled beneath her surface just like the flesh simmering beneath the thick soup in the iron pot beside them.” Mawu wastes no time in pressuring the other women to join her in escaping. (“Us is here in free territory and ain’t nobody thinking about making a run for it?” she taunts.) Meanwhile, they meet a white Quaker woman named Glory, who seems likely to help maneuver a getaway. The question of whether to stay or go is an easy one for Mawu, whose master is a cruel man. It is less so for the other women, especially Lizzie, who is genuinely fond of Drayle and can’t bear the thought of abandoning the two young children she has by him.

At home on Drayle’s Tennessee plantation, Lizzie is already set apart from most of the other slaves by her “house” status. But her sense of her own difference goes farther. She has come to see herself as Drayle’s nurturing partner, even as she understands clearly his role as her master. Her confusion is consistent with his treatment of her: He offers her many small kindnesses, clearly preferring her company to that of his wife, but denies her most ardent wish: that he will free their children. He teaches Lizzie to read but also uses her brusquely for sexual pleasure.

Being “taken” is a wearisome, numbing task of daily life for all the enslaved women, and Perkins-Valdez makes the reader feel the burden of this quiet brutality in writing that’s bold but unsensational. “[H]e pushed her onto the bed. She lay flat on her stomach and waited. … As he talked he stuck it inside of her and she did what she always did: clung to the words, wrapped them up inside, let them work her over. It was mainly this, his careful voicing of loving things that kept her in this place of uncertainty about her children,” she writes.

It’s not difficult to develop deep sympathy and affection for each of the slave mistresses, but, in a surprising turn, Perkins-Valdez makes it far more difficult to despise Drayle. Lizzie’s relationship with him seems more reminiscent of a particularly subordinate 1950s housewife and her husband than that of master and slave—at least while the two are at Tawawa. “Inside the cottage, Lizzie felt human,” writes Perkins-Valdez. “She could lift her eyes and speak the English Drayle had taught her. She could run her hands along the edges of things in the parlor … as if they were hers. And she could sit.”

Mawu observes Lizzie’s love for Drayle and quickly calls her on it: “He not your man, you know,” she says bluntly. But as Perkins-Valdez shows again and again, Lizzie’s thinking may not be so off the mark. Is he her lover? This man who, in effect, repeatedly rapes her? Who refuses to free his own children? It’s a difficult idea to accept—both for the reader and for Lizzie. But the viability of such a love is a question that Perkins-Valdez explores nonetheless.

The novel’s second section travels back several years to trace the evolution of Lizzie’s relationship with Drayle. Perkins-Valdez shows how Drayle wins Lizzie’s trust by teaching her how to read: “He brought her books. The first word she learned to read and write was ‘she’ and it delighted her so much she wrote it everywhere she could.” She reveals how Lizzie comes to share a bedroom with Drayle in his house, right across the hall from Fran, his wife, and how Fran falls in love with Lizzie’s children by Drayle as if they were her own.

The novel’s second section travels back several years to trace the evolution of Lizzie’s relationship with Drayle. Perkins-Valdez shows how Drayle wins Lizzie’s trust by teaching her how to read: “He brought her books. The first word she learned to read and write was ‘she’ and it delighted her so much she wrote it everywhere she could.” She reveals how Lizzie comes to share a bedroom with Drayle in his house, right across the hall from Fran, his wife, and how Fran falls in love with Lizzie’s children by Drayle as if they were her own.

In time, of course, their presence is no longer convenient, and Lizzie and her children are dismissed to the slave cabins, their elite status all but revoked. But Drayle eventually returns to Lizzie’s arms, keeping her in the awkward role he’s assigned her to, a role that revolves around being taken: “He entered her forcefully while she was still muddled in her thoughts. And then she could think no more except to understand that his desire for her was all she had. He moved on top of her, and it was as if a world moved on top of her, its weight at once delightful and burdensome.”

For every tenderness, there’s an equal and opposite action on Drayle’s part—some slight that tells Lizzie, and the reader, that he will never cast off his slaveholder identity—right down to the book’s closure and his final generous act toward Lizzie (one into which, interestingly, Perkins-Valdez weaves another real-life thread). Readers feel the sting of every contradiction right along with her, and we’re drawn tighter into the novel’s grip, our ambivalence about Drayle heightened, our care for Lizzie deepening as she’s faced with the most difficult decision of her life. Perkins-Valdez offers no pat answers, no final judgment, but this novel, full of so many unspeakable sorrows and injustices small and large, manages to end on a satisfying, even happy, note.