Committed

Every year the Mountain Heritage Literary Festival in Harrogate attracts dozens of people who are crazy about writing

On the first day of the Mountain Heritage Literary Festival—held June 24-26 at Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee—poet and teacher Aaron Smith described the moment the owner of a beer joint in Bassett, Virginia, shot his grandfather. “If you don’t leave, I’m going to shoot you,” she hissed, and he said, “Go ahead and shoot me.” So she did.

“I think you need some of that fearlessness to be an artist,” Smith concluded, “to make your work and stand by it no matter what anyone says.” (Also worth noting: it wasn’t a fatal shot.) You can’t write to make your parents happy, he said, and if your spouse doesn’t like what you’re writing, don’t show it to him or her. In fact, Smith always tells his students to write a poem titled “Things I Could Never Tell My Mother.”

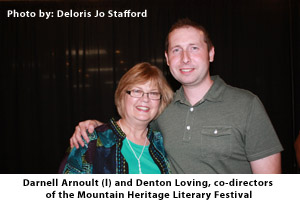

Smith’s sister, Nashville songwriter Belinda Smith, perched two chairs away, holding her guitar. Their first cousin once removed, novelist Darnell Arnoult (festival co-director, with Denton Loving), sat nearby. The three took turns sharing juicy bits of family lore—like the mysterious postcards to Arnoult that were signed “Loving you, Elvis”—and the poem, song, or story they’d each written about them. Instead of fighting over material, they all used it, with drastically different results, a fact which proves Arnoult’s point that no one can steal your idea because no one else is capable of doing with it exactly what you would have done.

The session also illustrates why this festival’s participants so often praise the gathering’s supportive, noncompetitive atmosphere. Arnoult compared it to a family reunion—one, this year, with eighty-two participants. Arnoult credits the warm, supportive environment to Appalachian-born author Lee Smith, whose name came up repeatedly at the festival. “Lee is a nurturing teacher,” said Arnoult, “who has made it part of her mission to help other writers, particularly writers connected to this region.”

The session also illustrates why this festival’s participants so often praise the gathering’s supportive, noncompetitive atmosphere. Arnoult compared it to a family reunion—one, this year, with eighty-two participants. Arnoult credits the warm, supportive environment to Appalachian-born author Lee Smith, whose name came up repeatedly at the festival. “Lee is a nurturing teacher,” said Arnoult, “who has made it part of her mission to help other writers, particularly writers connected to this region.”

Founded six years ago by author Silas House, then LMU’s writer-in-residence, the two-and-a-half-day gathering is packed with lectures; workshops in fiction, nonfiction, and poetry; readings by teachers as well as students; a play; and multiple concerts. (I attended as many sessions as possible before falling asleep under an oak tree.)

According to House, being an Appalachian writer is more a state of mind than a state of writing within a set of borders. “A love and understanding of the mountains and their culture is key in being an Appalachian,” he said in an interview with Chapter 16. “There are so many misconceptions about Appalachia, and as a writer from the region I think we have a responsibility to tell the truth—never to romanticize or villainize, but to articulate the complex truth about the place, exposing its beauty and dignity but also its sorrows and problems.”

Rebecca Elswick, an English teacher in Grundy, Virginia, and one of many participants making a return appearance, told Chapter 16 that coming to this festival “is the first thing I get to do for myself after being the nice teacher all year. This is where I can sit back and breathe, and recharge my writing batteries.” While other people also said they came to escape their daily routines, an equal number described the festival as a chance to live their real lives. Elswick agreed with Arnoult’s comparison of the festival to “a good old-fashioned homecoming,” adding that it’s “like having relatives coming from far away that you’ve never met before. It’s as if we’ve got our own secret society and the only requirement is that you’re from here—and that you know how to pronounce ‘Appalachia.’ ” (Dear Reader, in case you do not know, as I did not, the “correct” pronunciation includes no long vowels. Among this crowd, saying it with a long middle ‘a’ will be met with extreme distress.)

Rebecca Elswick, an English teacher in Grundy, Virginia, and one of many participants making a return appearance, told Chapter 16 that coming to this festival “is the first thing I get to do for myself after being the nice teacher all year. This is where I can sit back and breathe, and recharge my writing batteries.” While other people also said they came to escape their daily routines, an equal number described the festival as a chance to live their real lives. Elswick agreed with Arnoult’s comparison of the festival to “a good old-fashioned homecoming,” adding that it’s “like having relatives coming from far away that you’ve never met before. It’s as if we’ve got our own secret society and the only requirement is that you’re from here—and that you know how to pronounce ‘Appalachia.’ ” (Dear Reader, in case you do not know, as I did not, the “correct” pronunciation includes no long vowels. Among this crowd, saying it with a long middle ‘a’ will be met with extreme distress.)

To Elswick, this festival—along with the annual weeklong Appalachian Writers Workshop at Kentucky’s Hindman Settlement School—has proven instrumental to her growth as a writer. At House’s behest last summer she began submitting her work to writing contests, with great results. After winning both first and third places in the Appalachian Authors’ Guild short-story contest, Elswick entered a Writer’s Digest Twitter contest for the best book pitch contained in a single tweet of 140 characters. Noting how many of the entries began, “This is a book about…,” Elswick lifted a line directly from her novel-in-progress: “Mama always said you can tell a real lady by the shoes she wears, but then nobody ever accused Mama of being a lady.” Chosen as one of fifty finalists, she submitted a 250-word synopsis of the novel, and won. Her book will be published next year by Abbott Press. Elswick cited the warm, comfortable atmosphere as what sets this festival apart from others. “Everyone’s willing not only to share their best writing practices,” she said, “but they’ll bare their souls to you and tell you what they’ve been through.”

At the end of Friday night’s dinner, over blackberry cobbler and vanilla ice cream, Mike Mullins, executive director of the Hindman Settlement School, presented the Lee Smith award to Silas House. (The modest House had been told he was to present the award to Mullins.) In bestowing the award, Mullins described their initial meeting, when the scrawny, twenty-five-year-old House asked to attend the Appalachian Writers Workshop and be permitted to sleep in a tent to save money. Mullins granted the request, telling House he could pitch his tent on the grounds, “as long as you shower every few days.”

The support House received as a young writer inspired him to start the Mountain Heritage Literary Festival. “The only way published writers ever got published in the first place,” House said, “is because some other writer encouraged and prodded them and offered them some kind of generosity. We have to pass it on. And that’s a function the MHLF serves—to provide a place where we can be generous to one another, and trade information and encouragement.”

This atmosphere no doubt explains why so many festival speakers were refreshingly unguarded. In a fifty-minute lecture called “Pushing Your Own Boundaries: Fiction as Commitment,” novelist Pamela Duncan opened with, “Anyone who wants to write fiction should be committed!” In the context of a writers’ conference, where jockeying for position can be common, Duncan’s honesty and self-deprecation were astonishing. “I’m not pushing my own boundaries,” she announced. “I’ve been stuck for three years.” On the white board behind her, she wrote the words FEAR and LOVE, noting that writing always comes down to one or the other. “I know what I need to do is sit my butt down in the chair and write stuff. My fear is that it’s not going to be good enough and I’ll have to throw it away. Bottom line is, start writing. I need to take my own advice.”

This atmosphere no doubt explains why so many festival speakers were refreshingly unguarded. In a fifty-minute lecture called “Pushing Your Own Boundaries: Fiction as Commitment,” novelist Pamela Duncan opened with, “Anyone who wants to write fiction should be committed!” In the context of a writers’ conference, where jockeying for position can be common, Duncan’s honesty and self-deprecation were astonishing. “I’m not pushing my own boundaries,” she announced. “I’ve been stuck for three years.” On the white board behind her, she wrote the words FEAR and LOVE, noting that writing always comes down to one or the other. “I know what I need to do is sit my butt down in the chair and write stuff. My fear is that it’s not going to be good enough and I’ll have to throw it away. Bottom line is, start writing. I need to take my own advice.”

Duncan’s openness about feeling blocked was oddly inspiring—a hallmark of the MHLF. “So many conferences are stratified and full of posturing,” Arnoult explained, “with everybody sucking up to who might help them with their careers, with the writers in the power chairs pontificating. Here, the help is a given, as well as a healthy dose of humility. We all learn from each other.”

At Duncan’s talk, a woman in the audience raised her hand to ask how to make the transition from writing to real, everyday life: “Think of Tolstoy. You think when he was done writing he went into the kitchen and did dishes?”

Duncan’s response was swift: “No,” she said. “He had a wife. That’s what I need.” Everyone laughed.

Duncan’s response was swift: “No,” she said. “He had a wife. That’s what I need.” Everyone laughed.

Asked what makes writing worthwhile in spite of her litany of grievances, Duncan told a story about actress Julie Andrews. “She used to go see a therapist and she’d just complain about singing the whole time, and finally the therapist said, ‘Well, maybe you love it too much.’ And Andrews burst out crying.” Duncan paused, considering. “That’s true,” she said. “That’s how I feel about writing. I love it. And I need it.”

The classroom of writers applauded with the ardent conviction of those who believe that storytelling is a vital and important pursuit. They were committed. To representing Appalachia, to making peace with where they came from, to each other as a community of writers, and to the whole crazy-making lonesome endeavor of writing itself, they were committed.