A Gift for Adoration

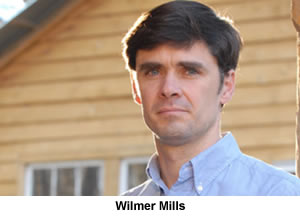

Celebrating the life and words of poet Wilmer Mills

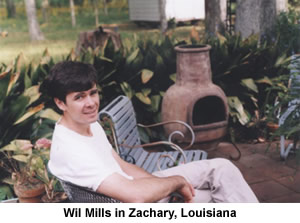

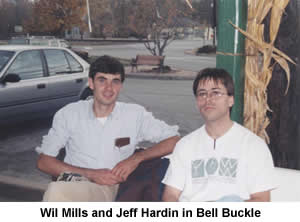

My friendship with Wilmer Mills goes back to the summer of 1990, when we were undergraduate poets selected for a summer workshop at Bucknell University. Roommates, we instantly began to share our poems and then just as soon began to argue about poetry. We haven’t always agreed, but for two decades we have challenged each other to expand our ideas about what poems could look like and sound like. What fun we’ve had! We went at it with zeal and curiosity, with arrogance and humility, with bewilderment and certainty. Wil’s poems are as central to my life as anything by Frost, Dickinson, Basho, Szymborska, Stafford, or any of the other writers I keep close.

On May 14, Wil called to tell me the news of his cancer. I was traveling home from a wedding in West Tennessee, and he asked me to find a place to pull off the road. I wasn’t concerned: Wil has a certain reputation, one might say, a stance toward technology that is at odds with our culture, and he abhors it when anyone talks on a cell phone while driving. (He spoke on this subject a few months ago at Covenant College in Chattanooga, where he was serving as writer in residence; to hear the talk, click here.) I soon found a rest stop and called back, only to hear him utter words like “small-cell carcinoma” and “in the time I have left.” I had just spent a couple of days with Wil and his family, and only a month and a half later, this horrible news was changing our voices. When I got off the phone, I couldn’t speak to my wife. I just sat there and wept.

On May 14, Wil called to tell me the news of his cancer. I was traveling home from a wedding in West Tennessee, and he asked me to find a place to pull off the road. I wasn’t concerned: Wil has a certain reputation, one might say, a stance toward technology that is at odds with our culture, and he abhors it when anyone talks on a cell phone while driving. (He spoke on this subject a few months ago at Covenant College in Chattanooga, where he was serving as writer in residence; to hear the talk, click here.) I soon found a rest stop and called back, only to hear him utter words like “small-cell carcinoma” and “in the time I have left.” I had just spent a couple of days with Wil and his family, and only a month and a half later, this horrible news was changing our voices. When I got off the phone, I couldn’t speak to my wife. I just sat there and wept.

For anyone who has been following—through his CaringBridge site—Wil’s battle with liver cancer, it is clear that something incredible has been going on. Displayed there is Wil’s remarkable testimony to the power of language, love, family, and faith in the face of a devastating diagnosis. Wil’s own updates and the messages shared by his family and friends have had a far-reaching impact, extending beyond his circle and into the lives of complete strangers, who have been drawn toward and into this family’s undeniable strength. The Bible tells us that the word of God shall not return void. Wil grounded his own writing life in the Bible, beginning each day with reading and prayer, and entering into his own poems within the light of God’s word. That was his process. The comments on CaringBridge make me think Wil’s words will not return void, either, but will move out into the world, profoundly affecting readers’ lives.

Almost two months ago, Wil sent me a short essay on time and the power of spoken words. He was considering posting it on CaringBridge, and he asked if I thought it was “inappropriate” for the site. As I read Wil’s draft (later revised and published at Chapter 16, here), I was humbled and astonished:

Time is not a cold finality but a fullness, a place in which to abide and to breathe deeply without respect to calendars and deadlines. It is where we are simultaneously most human and most divine. Too often we live only for the clock and fail to notice how in the absence of incremental time we would ironically be more able to see the pattern in the rug, how the stained glass windows of our lives make sense as wholes and not as mere pieces.

Wil and I have had such conversations for two decades now, as much a part of the fabric of our friendship as the topic of fishing, sports, or politics might be for other people. These words, though, all in the right order, seemed a stunning distillation of what Wil had been trying to say for years. “Please post it,” I wrote back. “Your words will be a consolation for many, as they have been for me.” Given the outpouring on CaringBridge, I believe they have helped others to understand not only how to face the fact of his death but how to adore the miraculous lives we have all been given, how to search out the mystery of why we have been gifted into the world, into each other’s lives.

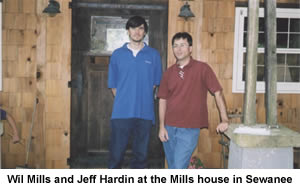

Wil brought a gift for adoration to everything he did. Among the countless writers who have passed through Sewanee, he was noted for his hospitality, originality, and individuality. Wil was his own man, firmly content in his boots, and everything he did in life reflected an artist’s sensibilities. He was a maker, conceiving and building a specific kind of existence within the world. His house in Sewanee is a marvel, and every last detail—from the piano strings inset into the wall leading upstairs, to the inglenook beneath those stairs with built-in bookshelves and overhead light—he conceived of within his own sense of time. The spaces he built—whether in rooms of houses, rooms of poems, or rooms of conversations—became spaces of an imagined existence I always stood in awe of.

Wil brought a gift for adoration to everything he did. Among the countless writers who have passed through Sewanee, he was noted for his hospitality, originality, and individuality. Wil was his own man, firmly content in his boots, and everything he did in life reflected an artist’s sensibilities. He was a maker, conceiving and building a specific kind of existence within the world. His house in Sewanee is a marvel, and every last detail—from the piano strings inset into the wall leading upstairs, to the inglenook beneath those stairs with built-in bookshelves and overhead light—he conceived of within his own sense of time. The spaces he built—whether in rooms of houses, rooms of poems, or rooms of conversations—became spaces of an imagined existence I always stood in awe of.

A couple of weeks after Wil called with his news, I acknowledged my own difficulty with his terminal diagnosis:

I can be driving down the road, and all of a sudden I’m overcome with emotion. I wake up first thing in the morning, and it’s as though I’m already weeping, or have been in my sleep. As you say, there is freedom—there really is—in living within time, and within all that means, part of which is the knowledge of its passing and our own place within it. The grief is deep, but praise is what we were made for, and I step into it with all that I am. I hold you up before God and say, “Thank you!” I can’t believe our paths ever crossed, but here we are, within this space of time, sharing it, as we have for two decades. This fact can only be another part of the mystery of God’s grace.

More than fourteen years ago, Wil was the first person I told when my wife found out she was pregnant with our first child, Storie. The next year I got the same call when he and Kathryn were expecting Benjamin. When either Wil or I had work accepted by literary journals (The New Republic, The Southern Review, The Hudson Review, Measure, and others), we couldn’t wait to share the good news. The phone would ring, and I knew his voice immediately, as he did mine. We swapped poems and criticisms and cheered each other on our entire adult lives, genuine fans of each other as well as each other’s work.

One time a few years ago, on a July 4th weekend, Wil called to ask if I would come to Sewanee and help him bake bread all night in an outdoor oven he had built just for that purpose. He wanted to make something like a hundred loaves and sell them at the farmers’ market on Saturday morning and then later at an event at the University of the South—a homecoming, I think. What a night we had! We ground wheat, mixed and kneaded dough, rolled and shaped it into loaves and baguettes, and carried trays out to the oven. I had no clue what I was doing, but Wil loved to teach me how to do such things, all the while explaining elaborate histories about wheat, yeast, and ancient processes long forgotten in today’s fast-paced world. Sometimes I thought he was just making stuff up, but it all sounded so interesting that I didn’t challenge him.

One time a few years ago, on a July 4th weekend, Wil called to ask if I would come to Sewanee and help him bake bread all night in an outdoor oven he had built just for that purpose. He wanted to make something like a hundred loaves and sell them at the farmers’ market on Saturday morning and then later at an event at the University of the South—a homecoming, I think. What a night we had! We ground wheat, mixed and kneaded dough, rolled and shaped it into loaves and baguettes, and carried trays out to the oven. I had no clue what I was doing, but Wil loved to teach me how to do such things, all the while explaining elaborate histories about wheat, yeast, and ancient processes long forgotten in today’s fast-paced world. Sometimes I thought he was just making stuff up, but it all sounded so interesting that I didn’t challenge him.

While loaves baked and we had a free moment, we sat in the cool night air underneath the towering oaks and talked. Such moments feel holy to me in a way I can’t really explain, like entering a quiet space within an inglenook of time. Over the years, I shared many times like that with Wil: the two of us, the quiet air, and God listening in.

Often Wil would take out his guitar, and anyone who has heard him sing knows how intimate his voice sounds, how deeply tender and piercing his eyes can be. Or, as happened on that night, we “oohed” and “ahhed” like children at the smell of those loaves emerging from the oven, their thick crusts steaming, so fragrant we stood for a moment just breathing them in. Wil cut a loaf open for us to “sample,” and there in the middle of the night we ate it as though it were manna. When Wil liked something—the taste of figs, for instance, or a resonating, rich line in a poem—he would shiver his whole body with visible delight. In the moonlight the grins on our faces, I like to imagine, were visible to passing satellites, someone in a control room somewhere wondering what on earth those two grown men on that mountain in Tennessee could be so happy about.

I was at Wil’s house one day when his daughter, Phoebe-Agnès, was assisting him with a brick-laying project. Three or four years old at the time, she wore boots and held a trowel in her hand. “Bootsy,” Wil called her. After mixing mortar in a wheelbarrow, Wil slapped a thin layer down, firmly securing a single brick in place. Phoebe-Agnès took her trowel and scraped the excess mortar away. Each brick took a while, to say the least. They were the picture of inefficiency and beautifully so. Bound by clocks, adults often want only to get a task done as quickly as possible. In such a context, children are rarely brought into learning and shared responsibility. I’ve always admired Wil for how “time” doesn’t really exist for him in the way it does for others. What is time, if not this space we share together? What is time, if not our own creativity finding a space to flourish? Time is holy, and Wil existed in it without hurry, and I hope his daughter carries this memory, too, and a thousand just like it.

For many years Wil worked and re-worked a book he was calling Arriving on Time. That was his great subject, Time. As he wrote in his essay,

The simplest way to enter the fullness of time is by breathing our words aloud to each other, and often, with love and hope. The miracle of spoken language is that it insists on face-to-face contact, or, in the case of a letter, it brings the speaker’s spirit into the room in a real sense and in real time at the right velocity, the speed of breathing. It has the tempo of people eating a meal together. In this sense, Kairos Time and spoken language are two sides of the same Koinonia.

The simplest way to enter the fullness of time is by breathing our words aloud to each other, and often, with love and hope. The miracle of spoken language is that it insists on face-to-face contact, or, in the case of a letter, it brings the speaker’s spirit into the room in a real sense and in real time at the right velocity, the speed of breathing. It has the tempo of people eating a meal together. In this sense, Kairos Time and spoken language are two sides of the same Koinonia.

Wil called me one day many years ago just to talk to me about time and Biblical translation. First, he said, the translation of a verse like “And the word of God came to Moses” doesn’t really provide the full meaning. More accurately the verse should read, “And the word of God happened to Moses.” He loved that idea, that the word of God is outside the self and rushes in to happen to a person.

Secondly, he said, in Hebrew the idea of time isn’t like our conception of time. The closest we might come to understanding it would be to say “a space of appropriateness.” Since God is in control of time, he said, and since everything that happens within that time is by God’s design and providence, then time is only the accomplishment of what God intends to happen. This idea excited him immensely. Wil’s own life span, in our limited view, seems tragically short, but Wil would say that it was “appropriate” for whatever God needed to accomplish through him. Like anyone, he wanted to live a long life, but he also believed in being obedient to God’s purpose for his life.

Wil’s mind moved from architecture to woodworking to high-fructose corn syrup to wheat grass to the Apostle Paul, all in the same conversation. I could never predict what might emerge. And his wit often caught me off guard. Aware of my crush on Nigella Lawson, the cooking-show host, he delighted in writing a poem about her, just to poke fun at me, provoke a reaction. When the poem was published by Poetry magazine, I feared he might write a whole series of poems about my other crushes, beginning, of course, with Salma Hayek.

In late March, Wil gave the introduction when I read at Covenant College. I remember the joy on his face as he spoke from notes (but mostly from his heart) about me and my poems. To my astonishment and embarrassment, he said that his own writing moved back and forth between two pillars of influence: Richard Wilbur and me. As he said my name, his voice flushed with emotion so that he had to catch himself, choking back tears.

Earlier in the day, we had been talking about things we love. I didn’t realize he would use some of these ideas in his introduction, but when he did, I became the one who had to hide my emotion. Wil said, “Jeff Hardin loves spring, all the new blooms and the earth coming to life. Jeff Hardin loves his wife, his high-school sweetheart whom he married almost twenty years ago. Jeff Hardin loves poems. Jeff Hardin loves books. He carries boxes of them wherever he goes. Jeff Hardin will likely take all the money Covenant College pays him and go to McKay’s first thing in the morning and blow it all on books.”

Earlier in the day, we had been talking about things we love. I didn’t realize he would use some of these ideas in his introduction, but when he did, I became the one who had to hide my emotion. Wil said, “Jeff Hardin loves spring, all the new blooms and the earth coming to life. Jeff Hardin loves his wife, his high-school sweetheart whom he married almost twenty years ago. Jeff Hardin loves poems. Jeff Hardin loves books. He carries boxes of them wherever he goes. Jeff Hardin will likely take all the money Covenant College pays him and go to McKay’s first thing in the morning and blow it all on books.”

How I loved that last statement! Being known that way is one of the things I loved best about our friendship. He knew me, and I knew him. The audience erupted in laughter, and I feigned bewilderment, but then, under the glare of those faces turned toward mine, I nodded a reluctant agreement. Here we all were, strangers sharing this intimate space together. As poems ask us to do. As Wil’s last months did, bringing so many people together from different parts of the country and the world. Strangers to each other but not to Wil. And not exactly strangers any more to one another.

“Jeff Hardin loves Wil Mills.” I wish I’d thought to say those words when I rose to read my poems that night. I would have been stating the obvious, of course, but it would still have been right to speak those unexpected words before a crowd, if only to embarrass both of us and have a good laugh within the joy of truth and friendship.

I last visited Wil in Sewanee toward the end of June—less than a week later, he would enter hospice care at his parents’ home in Zachary, Louisiana. We spent the day together. He was tired and drowsy, but we managed to review a few of his poems. He called them “Facebook” sonnets. I knew some of them already, but there were a couple of new ones I hadn’t seen. I gave suggestions for revision—line edits and syntactical rearrangements—and then reordered the sequencing of the individual sonnets. He liked my ordering of his logic, how beginning with a particular sonnet set the tone for how to read those that followed.

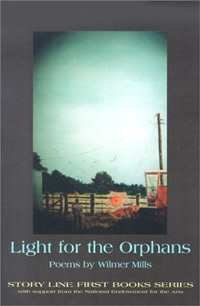

One time, years ago, he showed me a poem called “Confessions of a Steeplejack,” which later appeared in his collection, Light for the Orphans. Far down in the poem was this magical line: “the men who built old churches all have died.” I got goose bumps when he read that line aloud. I told him he had to make that line the opening of the poem. He argued with me, of course—that was Wil’s nature. He was stubborn, ornery, hard-headed to a fault. He claimed I didn’t understand what he was trying to do in the poem. I told him he was full of himself, that a reader encountering that line first would hear more deeply the heart of the poem. The change would require a lot of revision, a lot of hard work—the entire poem would have to be rebuilt from the ground up. “Maybe you’re not up for it,” I teased him. Then I told him that I’d beat the living crap out of him if he didn’t take my advice. He was taller, had a longer reach, but I warned him that I was scrappy. We both laughed. Sometime later, he rewrote the poem, starting with that magical line. It’s one of the gems in that collection, but then all of them are gems. Or “keepers,” as Wil would say.

Earlier this year, before we knew of Wil’s diagnosis, I sent him an email of encouragement about our writing. I often joked about how we had to help each other rebuild our shattered egos. Though we both have finished books that are yet unpublished, and though lack of recognition seems to be our mutual fate, I wanted to hold up between us an idea I had never really been able to form completely:

God’s really our only reader, the only one that matters anyway. I just think of writing as one of the ways I can follow what Phillipians 4:8 says: “Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.”

All the rest of it—the recognition, my spot on the stage, the next book publication—would be nice, but in the end, thinking on “these things” really is an astounding source of joy. It may have to be enough. Well, it is enough.

Wil wrote back with an enthusiastic “Amen!” I think he was finding that joy to be deeper and deeper the older he got. Selfishly, I wish he could have written forty more years’ worth of poems. Perhaps he would have moved from the Proverbs and Lamentations his poems often were to something like his own brand of Psalms. I don’t want to be selfish, though. I want to stand in awe of the words he wrote. Like him, once upon a time, they never existed. Now they do, inexplicably present in a fullness that didn’t exist before.

Wil wrote back with an enthusiastic “Amen!” I think he was finding that joy to be deeper and deeper the older he got. Selfishly, I wish he could have written forty more years’ worth of poems. Perhaps he would have moved from the Proverbs and Lamentations his poems often were to something like his own brand of Psalms. I don’t want to be selfish, though. I want to stand in awe of the words he wrote. Like him, once upon a time, they never existed. Now they do, inexplicably present in a fullness that didn’t exist before.

On the afternoon of our last visit, Wil wanted me to take him for a drive. He had hoped we could sit on the porch of Sterling’s Coffee House and talk poems, but he wasn’t feeling well enough. Instead, we drove out to the giant cross that overlooks the town of Cowan. A young couple was there, out a ways from where we sat in my car. Seeing them, we talked about how wonderful it was to be in love with our wives. Since the chemotherapy wasn’t shrinking his tumor, we talked about the possibility of hospice care, too. When he received the diagnosis, he had thought he might live perhaps a year, but he was coming to terms with a much shorter time. He was trying to prepare me for the days ahead, now approaching much faster than either of us had thought they would. We talked about his beautiful and extraordinary children, Benjamin and Phoebe-Agnès, and of how his wife Kathryn was ministering to him in these last days. He hated to leave them behind. That reality worried him more than anything.

When we were backing out of our parking space, I looked out my window and stared for a moment at the towering cross, a small fence surrounding it. I said, “Seems like we ought to pray.” Wil agreed. We pulled back in and made our way to one of the benches. Wil had always had such long strides and walked like a bullet, but now I was the one who had to be conscious of slowing my pace. We sat, and I prayed, asking God to abide with Wil and to make his presence fully known to him. When I was finished, I didn’t expect that Wil would pray too.

I have to ask this question: have you ever been prayed for by a dying man? Have you ever heard someone, aware of his own dying, ask God to help you accept His providence? I’m still astounded when I think about that kind of selflessness, that kind of humility. Wil’s words, like all of our words, like the lives we’ve been given, can never be unspoken. Wil expressed gratitude for our friendship and for placing us in the lives of each other to share this journey of words together. He asked God to carry forward our words and deeds to accomplish what He wanted to. I wish I could hear that prayer again because it rose out of the deepest and most loving place inside Wil. It was like a beautiful poem the world will never know, shared only between the two of us and God. It lived only on the air between us, in the intimate space we shared.

Copyright (c) 2011 by Jeff Hardin. All rights reserved. Jeff Hardin, a native of Savannah, Tennessee, is a professor of English at Columbia State Community College. A graduate of Austin Peay State University and the University of Alabama, where he received an M.F.A. in creative writing, Hardin is the author of two chapbooks, Deep in the Shallows (GreenTower Press) and The Slow Hill Out (Pudding House), as well as one book-length collection, Fall Sanctuary, recipient of the Nicholas Roerich Prize.