Discovering the Story by Writing It

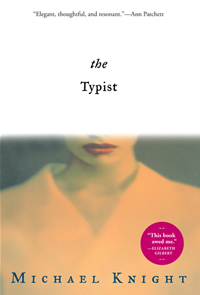

Michael Knight’s acclaimed World War II novel, The Typist, is released in a new paperback edition

Frederick Barthelme once called Knoxville fiction writer Michael Knight “a genius of the ordinary.” Indeed, Knight cut his literary teeth by writing compressed, elegant short stories that suggest a fusion of Peter Taylor or Walker Percy and Amy Hempel or Raymond Carver. Yet in The Typist, Knight departs dramatically from his typical milieu with a stirring, engrossing tale set in Tokyo during the aftermath of World War II. Marvelously, The Typist contains all of the ambition and intrigue of the best World War II novels while retaining the understated grace and quiet perceptiveness of the small but critical moments in life on which Knight’s reputation has been built.

With The Typist, Knight has produced a short work encompassing a variety of richly drawn characters, themes, and emotions typically associated with much longer novels. The Typist parses a variety of complications involving love, betrayal, and political maneuvering in Tokyo during the occupation years following World War II. Knight’s graceful, lyrical prose calls to mind the work of Tobias Wolff and Richard Ford, and the novel’s deceptively intricate plotting invites comparison to Alice Munro. Since its release last year, The Typist has received uniformly rave reviews and was named to numerous best-of lists, including The Huffington Post’s “10 Best Books of the Year” and the “Top 100 Books of the Year” at both The Kansas City Star and the California Chronicle. More tellingly, many of Knight’s peers have championed The Typist, including Ann Patchett, who called it “elegant” and “resonant,” and Richard Bausch, who praised it as “a beautiful portrait of a kind of walking pneumonia of the spirit that seeks and finds its own cure.” “I believed and breathed every single word,” wrote Eat, Pray, Love author Elizabeth Gilbert. “This book awed me.”

Earlier this month The Typist was published in paperback, an edition which includes the short story “The Atom Bowl,” a sort of prequel to the novel. On the occasion of its release, Michael Knight answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Earlier this month The Typist was published in paperback, an edition which includes the short story “The Atom Bowl,” a sort of prequel to the novel. On the occasion of its release, Michael Knight answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Chapter 16: Most of your publications are short stories; in interviews, you’ve been a staunch advocate of the form and have expressed some resentment at its diminishing audience. The Typist evolved from a short story, “The Atom Bowl,” which is included in the new paperback edition of the novel. What relationship do you see between the conception and/or composition of short stories and novels? Does the content dictate the form, or vice versa?

Michael Knight: The relationship between The Typist and “The Atom Bowl” is more complicated than that. Both the story and The Typist evolved from a failed attempt to write a novel told in third-person-multiple-point-of-view narration centering on the participants in this bizarre but sort of wonderful football game played at the site of the Nagasaki bombing. I worked on that version for almost a year before conceding defeat. It was all idea. A cool idea, to be sure; I just couldn’t get my head around it. But I loved the time and place and the concept, and eventually, maybe two years later, I came back to it with this more focused first-person approach that evolved into The Typist. When the novel was finally finished, I returned to some of those discarded early pages and found the story, “The Atom Bowl,” in them. So I learned how to write The Typist by failing to write that original third-person version, and I learned how to write the story by finally succeeding to write The Typist. Does that make sense? I’m not sure what that says about form and content. Likely it says more about my own trial-and-error approach to writing fiction.

Chapter 16: With few exceptions, your published work has tended toward the contemporary-realist genre: stories set mostly in relatively genteel Southern milieus. A World War II novel set in post-war Tokyo in which Douglas MacArthur appears as a pivotal character could be fairly called a departure. How was your approach different in writing The Typist? How did you manage the tension between the novel’s historical and imagined/imaginative elements?

Knight: Honestly, beyond the reams of necessary research, my approach wasn’t all that different. I don’t want to over-generalize or to sound like I’m disparaging historical fiction—I’m not!—but sometimes it seems to me that in “historical” novels there’s a distance between narrator and subject that I don’t particularly enjoy as a reader. Historical novels can feel stuffy. As much history lesson as story. Almost as if the writer wants to display the depth of his or her research. But as a reader, I’m not interested in, to pick a random example, a twelve-page discourse on Victorian table manners. I’m interested in characters and I don’t think people in Victorian England were fundamentally much different than people in post-WWII Japan or contemporary Tennessee. And they don’t know that they’re participating in “history.” They’re just living their lives. I did enough research that I could feel grounded in the time and place, that I wouldn’t have to think about capitol-H history all the time, that my knowledge of time and place could provide an imaginative context. Then I tried to set all that research aside and focus on the people and the story. I wanted The Typist to feel personal, like it’s being told by someone who experienced the time rather than by a student of the time.

Knight: Honestly, beyond the reams of necessary research, my approach wasn’t all that different. I don’t want to over-generalize or to sound like I’m disparaging historical fiction—I’m not!—but sometimes it seems to me that in “historical” novels there’s a distance between narrator and subject that I don’t particularly enjoy as a reader. Historical novels can feel stuffy. As much history lesson as story. Almost as if the writer wants to display the depth of his or her research. But as a reader, I’m not interested in, to pick a random example, a twelve-page discourse on Victorian table manners. I’m interested in characters and I don’t think people in Victorian England were fundamentally much different than people in post-WWII Japan or contemporary Tennessee. And they don’t know that they’re participating in “history.” They’re just living their lives. I did enough research that I could feel grounded in the time and place, that I wouldn’t have to think about capitol-H history all the time, that my knowledge of time and place could provide an imaginative context. Then I tried to set all that research aside and focus on the people and the story. I wanted The Typist to feel personal, like it’s being told by someone who experienced the time rather than by a student of the time.

Chapter 16: One of the most intriguing aspects of The Typist is your representation of MacArthur and his son, Arthur. General MacArthur is doubtlessly among the most famous generals in American history, and many of your readers may not realize that the real Arthur MacArthur changed his name as an adult to escape the pressure of his paternal legacy. How did you conceive the idea of weaving the General and his son into the narrative of The Typist? What drew you to Arthur MacArthur as a character, and what challenges did you face in representing such recognizable historical figures in the imagined context of a novel?

Knight: Given the time and place and the narrator’s occupation, I knew General MacArthur would have to figure into the story somehow—the challenge of “imagining” such a prominent historical figure was intriguing on its face—but I had no idea Van’s relationship with Arthur would become what is to me, in many ways, the heart of the novel. That was as much a surprise to me as anybody else, and that’s not so unusual a far as my process goes. Discovering the story is one of the things that make writing fiction exciting.

In American Caesar, William Manchester’s biography of MacArthur, I came across the image of Arthur MacArthur alone, paddling a rowboat around a swimming pool, this lonely, quirky, beautiful image, exactly the sort of image I’m drawn to in any fiction, historical or otherwise, my own or someone else’s. And it dawned on me that in all the MacArthur biographies I read, much is made, for obvious reasons, of the general as a strategist and a statesman, even as a husband, but there wasn’t much at all on MacArthur as a father. Given the choices that Arthur MacArthur has made as an adult to separate himself from his father’s legacy, it’s not too big a leap to imagine a complicated relationship. To say the least.

So there was this sort of emotionally charged blank space in the history into which I could imagine the characters, this space separate from the historical record that I could kind of claim as my own. All of the scenes between the MacArthurs and the narrator are pure invention, which helped me understand them as human beings beyond history and biography. And these imagined relationships provide a context for some of the literal history. I had an idea, for example, that I wanted to include the war-crimes trials in the novel but I didn’t know how exactly and I knew I couldn’t write the trial unless it mattered to the story. In the final draft, Van takes Arthur, at his father’s request, to see Tojo testify. The trial highlights some of the novel’s thematic and political elements, but the scene itself isn’t about what happens on the witness stand. It’s about Van and Arthur and what’s happening between them on a personal level.

Chapter 16: Though The Typist is set in post-war Japan, its narrator, Francis Vancleave, is an Alabama boy, and the style and sensibility of the novel is distinctly Southern, from Van’s mannered perspective to his reverence for the Crimson Tide football team. Walker Percy famously resented being called a Southern writer; Richard Ford is another native Southerner who, until recently, chose to distance himself from such labels or regional identifications. Do you consider yourself a Southern writer? Are such assignations meaningful or counterproductive in the current literary climate?

Knight: I grew up in South Alabama and was weaned on Alabama football, and everything I know is either a consequence of my past or a reaction against it, so a certain amount of Southernness, whatever that means, is inescapable. My personal experience is the lens through which I see the world. In that sense I am and always will be a Southern writer, and my imagining of post-WWII Japan is bound to be influenced by my Southerness. Now, is that designation useful or enlightening in some way? I have my doubts. My experience of the South is fundamentally different from Tom Franklin’s, for example, and Michelle Richmond’s and Brad Watson’s and William Gay’s, to name just a few Southern writers I admire.

Chapter 16: The Atom Bowl is a heartbreakingly well-meaning but ill-advised gesture on the part of General MacArthur, who, up to that point, exhibited such extraordinary sensitivity to the Japanese in their protracted moment of defeat and humiliation. How did you happen upon this plot detail? How crucial was it in the development of The Typist?

Knight: I first became aware of the Atom Bowl, an actual football game played on the site of the Nagasaki bombing by college football players stationed in Japan after WWII, in a 2005 New York Times article commemorating the event. And it was absolutely crucial to the development of the novel. I’ve already rambled a little about how The Typist evolved but without the Atom Bowl I most likely wouldn’t have begun researching post-WWII Japan.

Even after I’d abandoned my original conception for the book, the Atom Bowl was out there looming in my imagination. I knew I wanted my narrator, Van, to bear witness to the game, and it began to make sense that the game could work as a sort of climatic moment for his experience in Japan, rather than its focus. All the complexities of the time and place are present in “The Atom Bowl”—the devastation of the war and of the Japanese people, MacArthur’s good intentions exemplified in what I imagine as a particularly American combination of certainty and naïveté. I wasn’t sure if or how the story would eventually take him there but the fact of the Atom Bowl provided the entire experience of writing the novel with a kind of forward lean, something to aim for as I progressed.

Chapter 16: The Typist has earned rave reviews and been named to a number of best-of lists. It’s an unusual novel in the sense that it captures such a broad range of themes and presents a relatively complex and extremely satisfying plot in less than 200 pages. Do you think you’re onto something here? Is the long novella or short novel the ideal, happy medium in a world in which both short stories and longer, more complicated literary novels seem to have little audience?

Knight: If by “onto something,” you mean have I happened upon some commercial or artistic secret, then the answer is, alas, no. I wish. I think it has more to do with my taste as a reader and my affinities as a writer. I cut my teeth writing short stories and what I love about short fiction is that a good story takes a novel’s worth of emotional complication and compresses it into a much smaller space. There’s instant tension, beyond the conflict in the story, between form and content. When it works, it can make for a read that’s more intense than most novels. My emotional experience of a novel is generally more diffuse. As a young reader and an aspiring writer, the novels I admired—The Great Gatsby, The Sun Also Rises, As I Lay Dying, Catcher in the Rye, to name but a few—the ones I most wanted to emulate, they’re all relatively short. I think that has less to do with my attention span than with the intensity of the reading experience. My hope as a novelist is to combine short-story-like intensity with a more extended development of character and subject and theme and so forth. The short novel just happens to be suited to my intentions.

Chapter 16: As an Alabama fan teaching at the University of Tennessee, do you consider yours a divided soul?

Knight: I hope Tennesseans will forgive me, but my heart is still firmly with the Crimson Tide. We’ve lived in Knoxville for ten years now, however, and we love it, and it feels like home, so I’ve made my peace with the Volunteers. We’re avid Lady Vols fans. Pat Head Summit is the Bear Bryant of women’s hoops. A couple of years ago my oldest daughter, Mary, came home from school with this very serious look on her face and said, “Dad, there’s something I need to talk to you about,” and I immediately thought, “Oh no, I’m not ready for this!” But what she said was, “I don’t think I want to be an Alabama fan anymore. I think I want to be a Tennessee fan now.” That’s as it should be. She’s a Knoxville girl. She ought to pull for the Vols. But on the third Saturday in October, I still want Alabama to whip her team’s butt.

Michael Knight will discuss The Typist at Union Ave. Books in Knoxville on August 27 at 6 p.m. To learn more about the novel, read Chapter 16’s review, here.