The Twang and Flavor of Speech

Poet Jeff Daniel Marion speaks of poetic discoveries in a disappearing rural world

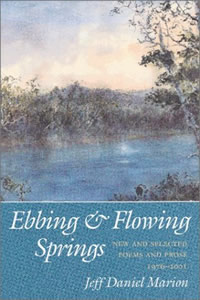

Jeff Daniel Marion, a native of Rogersville, Tennessee, is the author of twelve poetry collections, including The Chinese Poet Awakens, Letters Home, Ebbing & Flowing Springs (the Appalachian Writers Association Book of the Year in 2003), and Father (winner of the 2009 Quentin R. Howard Poetry Prize). Last year he received the James Still Award for Writing about the Appalachian South from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. In addition to being a writer, Marion was for more than thirty years a professor of creative writing at Carson-Newman College; for twenty of those years he ran Mill Springs Press, producing chapbooks and broadsides from handset type. He was also the founding editor of The Small Farm, a poetry journal, which he edited from 1975 to 1980. He is married to poet Linda Parsons Marion and lives in Knoxville, where he serves as the University of Tennessee Libraries’ Jack E. Reese Writer in Residence.

Novelist Ron Rash notes that for “twenty-five years Jeff Daniel Marion has eschewed poetic fashion and poetic posturing, going his own way, making poems that are confident enough to speak quietly to us, even gently,” and former Poet Laureate Ted Kooser calls Marion a “master of guileless simplicity.” Prior to his appearance on February 20 as part of the Writers in the Library series at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Marion answered questions from Chapter 16 by email.

Chapter 16: Some writers easily point to what brought them into the desire to write—sound, for instance, or the love of stories, or clear images, etc. Can you identify your early impetus for writing poems?

Jeff Daniel Marion: In the fifth grade at Rogersville Elementary School, I specifically remember the day our teacher, Mrs. Arnott, informed us that after lunch we would have a program that involved class participation—someone would lead the pledge to the flag, another would lead us in a song, and we’d conclude with someone performing in some way for the class. My buddy, Wayne Price, leaned over and whispered to me, “Danny, you get up and tell us a story!” Then, in an even lower voice, he gave the key command: “And make it long, so we won’t have to do any more work this afternoon!”

Jeff Daniel Marion: In the fifth grade at Rogersville Elementary School, I specifically remember the day our teacher, Mrs. Arnott, informed us that after lunch we would have a program that involved class participation—someone would lead the pledge to the flag, another would lead us in a song, and we’d conclude with someone performing in some way for the class. My buddy, Wayne Price, leaned over and whispered to me, “Danny, you get up and tell us a story!” Then, in an even lower voice, he gave the key command: “And make it long, so we won’t have to do any more work this afternoon!”

I accepted the challenge and wove my story from the B-grade Western I’d seen the past Saturday at our local theater, the Roxy, and from comic-book stories I’d read, as well as anything that came to mind. No one seemed to worry that I might change a character’s name midway in the story or that I’d introduce new characters at the end. I was free-wheeling and having fun inventing as I went along, sometimes propelled by the story itself to who knows where. I’d never experienced in quite the same way the thrill and adventure of words leading to other words to anywhere I might want to go or to anywhere the story might want to go.

That was sixty years ago, and the adventure goes on, not in a way I’d have thought then, but following many paths—in teaching and in writing, not only poetry, but also fiction and essays and a children’s book. When Letters Home was published, I gave a reading and book signing in Rogersville, and my former fifth-grade friend showed up and said to me, “Don’t you think your interest in writing started in fifth grade when you told those stories?” I have to say, thanks to Wayne Price I’m a writer! And thanks to Mrs. Arnott for allowing us to be creative!

Chapter 16: Have your motivations to write poems changed over the years?

Marion: My motivations to write poems have remained relatively constant over the years—that is, to capture vividly and explore the world as I see it, primarily the natural and rural world, its places, inhabitants and their ways of being, the twang and flavor of their speech. I am motivated to enter into the writing of a poem by the need to discover whatever there is in that feeling that’s so tantalizing, but at the moment unknown. I hope when someone reads the poem he or she will have made discoveries through the journey of the poem.

On the other hand, my means of making these discoveries has evolved over the years. I began primarily writing lyric poems with a narrative or two here and there. Most of the early poems are highly imagistic and painterly. That evolved to more character-driven poems along with a more open form and later syllabic lines. Now I’m back to some more lyrical poems, but at the same time I’m exploring the possibilities of the poem as a kind of letter giving intimate details of a life—sort of following Emily Dickinson’s comment that “these are my letters to a world that never wrote to me.”

Chapter 16: What early models shaped your first understandings of what poems could do or be? Have you departed from any of these models? Have you modified, in any way, your conceptions of how to write or construct poems?

Marion: There were many early models that shaped my first understandings of what poems could do or be, but two stand out prominently for me. As a junior at the University of Tennessee in Nathalia Wright’s American Literature course, I first read Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death,” and on the twenty-ninth or so reading of that poem, I said to myself, “Oh . . . .” I realized for the first time how poems are made of images, how these images create patterns and how those patterns make meaning. The understanding of that poem has been the basis of my understanding of every other poem I’ve read. How important it was for me to realize in that poem that rereading and rereading a poem is a necessary, natural process of experiencing its layers of richness and depths of meaning. Poems only unfold themselves through time devoted to them, through the evolution of our own unique perceptions.

Marion: There were many early models that shaped my first understandings of what poems could do or be, but two stand out prominently for me. As a junior at the University of Tennessee in Nathalia Wright’s American Literature course, I first read Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death,” and on the twenty-ninth or so reading of that poem, I said to myself, “Oh . . . .” I realized for the first time how poems are made of images, how these images create patterns and how those patterns make meaning. The understanding of that poem has been the basis of my understanding of every other poem I’ve read. How important it was for me to realize in that poem that rereading and rereading a poem is a necessary, natural process of experiencing its layers of richness and depths of meaning. Poems only unfold themselves through time devoted to them, through the evolution of our own unique perceptions.

The second poem I’d name here is William Stafford’s “Travelling through the Dark.” Again, I recall the exact circumstances of my reading that poem: fall, 1969, in a classroom on the second floor of Henderson Hall, where I was teaching freshman composition at Carson-Newman College and my students were writing an in-class essay. I’d just received Stafford’s book of the same title. I recall looking up from reading and glancing out the wavy-paned windows at the campus maples turning gold and yellow. I felt a stirring inside and knew I had been deeply moved in ways I only dimly understood. Momentous—I knew a great moral decision had been made in that poem, so subtly and powerfully. The poem shows we are a part of the whole of society and nature, and so often we must decide and respond to a situation not of our making or causing, but the situation demands that we choose. And in choosing, we enter the complex web of gray. I saw how a seemingly simple poem and story can be a complex involvement and moral challenge for the reader. I saw, too, how a poem can be both conclusive and open-ended simultaneously.

“Travelling through the Dark” taught me how line breaks can heighten the poem’s movement and force as the eye travels down the page.

“Travelling through the dark I found a deer

dead on the edge of the Wilson River Road.”

The line’s turn from “deer” to “dead” leads us increment by increment to discover naturally the gravity of the situation. A lesser poet might have written “Travelling through the dark I found a dead deer . . .” and found the impetus for the poem dead from the beginning. The seemingly simple placement of “dead” after “deer” in the turn from line one to line two propels the poem forward as we discover element by element the entire complex situation.

Chapter 16: Many poets look back upon their own early work sometimes with embarrassment, sometimes with tenderness. Do you have an early poem you still find important or crucial to your own sense of yourself as a poet? For new readers of yours, how might this poem be a good window into understanding what your poems are about?

Marion: “American Primitive: East Tennessee Style” is still important to me as representative of what drives me as a writer. In the first place, there’s the primitive, the raw and unrefined world—rusted gate and water barrels, tin can with water as humidifier. I’ve long been drawn to the “things of the world,” especially the worn and used, those so often overlooked and unremarked. Here I’m “painting” by focusing on the details, trying to render through sharply presented sensory details. As the speaker enters the gate, the hope is that the reader enters the world of the poem and follows along as the eyes and ears take in all these details. We’re all familiar with Grant Wood’s famous painting, and I wanted to suggest from that reference a means of painting with specific, sensory images through a voice with its rise and fall, its rhythms and moods—a kind of “spoken” painting, if you will.

For readers new to my work, this poem revels in the details of a fast-disappearing rural world. The poem literally describes my maternal grandmother’s house and yard, the world of my mother, six aunts and two uncles. I wrote this poem in the years 1968-69 when I lived in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, teaching at a small college and taking some graduate work at the University of Southern Mississippi. At that time I thought I had left East Tennessee and would never live there again. I was writing short stories and thought that at some point I’d write a novel. I was sure I was going to spend my life writing fiction. But when September ’68 gave way to October ’68, I’d expected the relentless heat to subside and October to reveal its colors as it did back in East Tennessee when I’d take to the mountains and fish for trout. But not so—and I began to feel twinges of longing to be back in East Tennessee with its changing seasons, back to my “homeland,” the mountains and valleys that had nurtured and sustained me. On Friday nights after a full day of teaching and after my two children had gone to bed, I sat at our kitchen table and wrote letters to friends and former colleagues and fishing buddies back home. That led me to remember my times there, my days spent at my grandmother’s, where I learned to fish, to name trees and plants, to discover fossils in rocks.

For readers new to my work, this poem revels in the details of a fast-disappearing rural world. The poem literally describes my maternal grandmother’s house and yard, the world of my mother, six aunts and two uncles. I wrote this poem in the years 1968-69 when I lived in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, teaching at a small college and taking some graduate work at the University of Southern Mississippi. At that time I thought I had left East Tennessee and would never live there again. I was writing short stories and thought that at some point I’d write a novel. I was sure I was going to spend my life writing fiction. But when September ’68 gave way to October ’68, I’d expected the relentless heat to subside and October to reveal its colors as it did back in East Tennessee when I’d take to the mountains and fish for trout. But not so—and I began to feel twinges of longing to be back in East Tennessee with its changing seasons, back to my “homeland,” the mountains and valleys that had nurtured and sustained me. On Friday nights after a full day of teaching and after my two children had gone to bed, I sat at our kitchen table and wrote letters to friends and former colleagues and fishing buddies back home. That led me to remember my times there, my days spent at my grandmother’s, where I learned to fish, to name trees and plants, to discover fossils in rocks.

While in Hattiesburg I had started to receive a new poetry journal founded and edited by my former college professor, mentor, and namesake for my son—Stephen Mooney. The Tennessee Poetry Journal contained work by such poets as William Stafford, Robert Bly, David Ignatow, and William Matthews, and a host of others. I hardly knew how to begin to enter this new world of poetry, but there at that kitchen table, late into a Friday night, I began to try to write poems. After many efforts and several weeks, in a moment of intense remembering and longing to be back in my homeland, I wrote “American Primitive: East Tennessee Style.” “Watercolor of an East Tennessee Farm,” its companion poem, was written in the same time period, and I look back on those two poems as being the very roots from which I came, both as a person and poet.

Chapter 16: I first encountered your poems, when I was an undergraduate, in the journal Zone 3, published by Austin Peay State University. You edited a small journal as well. Describe the role of small journals in the life of a practicing poet.

Marion: Small journals are the lifeblood of poetry in this country. They give the poet a sense of community, of a home and place of belonging for good work that otherwise might never be published. The best ones are sometimes a one- or two-person enterprise, a venture with a vision and a specific, unique sensibility. They played a major role in my development as a poet, especially Apple, a beautifully printed journal edited by David Curry and published in the early to mid 1970s. That’s where I first discovered the work of Kentuckian Richard Taylor, one of my longtime favorite poets. And certainly the most important journal for my development was the Tennessee Poetry Journal. That journal opened the world of contemporary poetry for me and published my first two poems.

Chapter 16: I have loved for many years your small collection, The Chinese Poet Awakens. How did this persona come to be?

Marion: The Chinese Poet Awakens was many years in the making. I think the origins really go back to 1961 when I was standing in Cole Drug Store, located on the corner of Cumberland and 17th Streets in Knoxville, looking through one of those revolving book racks so prevalent in that time period. My teacher Stephen Mooney asked me what looked good on the rack, and I chose a paperback anthology of Chinese poetry called The White Pony by Robert Payne. Mooney gave his approval, and I bought the book, my introduction to Chinese poetry in translation across several centuries. I was struck on first reading how fresh and accessible those poems were, as though the poets from four, five, or eight hundred years ago were speaking directly and clearly to me. I felt an immediate sense of connection across space and time. So that awareness and Asian sensibility were instilled in me through those poems—no doubt, somewhere in me the Chinese Poet poems were beginning to percolate.

In 1976 just after the appearance of my first book-length poetry collection, Out in the Country, Back Home, Puddingstone Press published my chapbook Watering Places, containing a piece called “Four Poems in the Manner of Lin Pu,” actually my first Chinese-inspired work. But a few years later when I took my son and daughter into a “petting tent” at the TV A&I Fair in Knoxville, a number of goats surrounded us once they saw we had food. One of them had apparently waited long enough for his share because he butted me from behind as I stood watching the goats being fed. A few days later I was thinking about the situation and began laughing—I knew I had to make something out of that situation. I recalled that my friend Mr. Wong, who owned a Chinese restaurant in town where several of us ate frequently, came to my table with his Chinese newspaper and pointed to a photograph of a Chinese poet who looked strikingly like me. Then he said, “You! Chinese poet!” and laughed. Thus was born the persona.

In 1976 just after the appearance of my first book-length poetry collection, Out in the Country, Back Home, Puddingstone Press published my chapbook Watering Places, containing a piece called “Four Poems in the Manner of Lin Pu,” actually my first Chinese-inspired work. But a few years later when I took my son and daughter into a “petting tent” at the TV A&I Fair in Knoxville, a number of goats surrounded us once they saw we had food. One of them had apparently waited long enough for his share because he butted me from behind as I stood watching the goats being fed. A few days later I was thinking about the situation and began laughing—I knew I had to make something out of that situation. I recalled that my friend Mr. Wong, who owned a Chinese restaurant in town where several of us ate frequently, came to my table with his Chinese newspaper and pointed to a photograph of a Chinese poet who looked strikingly like me. Then he said, “You! Chinese poet!” and laughed. Thus was born the persona.

When I wrote “The Chinese Poet Awakens to Find Himself Abruptly in East Tennessee,” I assumed it was a single poem—more time had to elapse before the second “Chinese Poet” poem would appear. And it was with the second poem that I began to realize potential in this speaker, this mask through which I could express a range of feelings and also connect across centuries and cultures. How freeing this mask was, giving me a lens through which to view my own experiences. I found a means to a greater simplicity, to a voice I felt had a sense of history as well as great range, along with an infinitely variable voice, allowing many moods as well as insights.

Chapter 16: Mark Strand, in his introduction to Best American Poetry 1991, writes, “Nothing else we read prepares us for poetry.” If we turn that idea around just a bit, what do you think poetry prepares us for?

Marion: Poetry prepares us to be better readers and listeners, more alert to the complexities of language, both written and oral. It prepares us to see through and not be swayed by dishonest uses of language, the pretentiousness of political rhetoric and its manipulative devices. In short, poetry prepares us to be better citizens.

Jeff Daniel Marion will read from his work on February 20 at 7 p.m. in the Hodges Library Auditorium at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.