Searching for the Poet Laureate of Music Row

In a new essay collection edited by Charlotte Pence, contemporary song lyrics finally earn the scrutiny of scholars

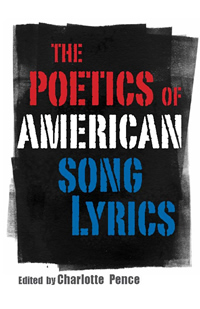

The Poetics of American Song Lyrics, an anthology of essays about the intersections between formal poetry and modern song lyrics, is divided in half. The first half is called “Poetic History and Techniques within Poems and Songs”; the second half is called “Analysis of Twentieth-Century Songwriters.” The first half theorizes a strong interconnectedness between poem and song, while the second half applies those theories to case studies. This split mirrors the division most readers assume between poetry and song. But the split, like the poem/song division itself, comes to feel almost arbitrary, as the essays in the second half contain much theorizing, as well, and the essays in the first half also rely on case studies. This blurring of boundaries is a smart move on the part of the anthology’s editor, Knoxville poet and Chapter 16 contributing writer Charlotte Pence: the form of the book, as does the form of any good poem or song, arises from its own argument. For Pence, who has taught poetry to fledgling songwriters at Belmont University in Nashville, the real point is that what separates poem from song is less than what unites them.

Which is not to say that Pence or her essayists ignore the obvious: poetry is written for the eye and songs for the ear. A line of poetry, for example, transmits its own music. This occurs via the line’s metrical construction and in its particular arrangement of consonants and vowels. The music (or deliberate lack of it) is inherent in the line. A line of song, however, requires instrumentation, which is why even the most memorable song lyrics can seem pedestrian on the page. (Think of Bruce Springsteen’s “Baby, we were born to run” or Louis Armstrong’s “And I think to myself / what a wonderful world.”) In his 2010 book, Finishing the Hat: The Collected Lyrics, Stephen Sondheim notes that “it is usually the plainer and flatter lyric that soars poetically when infused with music. [….] Music straightjackets a poem and prevents it from breathing on its own, whereas it liberates a lyric. Poetry doesn’t need music; lyrics do.”

Still, from the time of Homer to the Renaissance, poetry and song were inexorably linked. Because of this shared history, Pence’s anthology argues, much of the poetic tradition remains embedded in popular song. To demonstrate, Pence herself, in an essay titled “The Sonnet Within the Song: Country Lyrics and the Shakespearean Sonnet,” compares the structure of several hit country songs to that of the traditional sonnet. Citing the present-day grande dame of poetry criticism, Helen Vendler, Pence identifies the crucial element of a Shakesperean sonnet not as its rhyme scheme, metrical pattern, or line length, but rather its tight rhetorical structure, which features a progression and complication of a specific argument; a coda, or twist, at the end; and an emotional or psychic change in the speaker. Using these criteria, she analyzes “On the Other Hand” by Randy Travis, “Don’t Tell Me What to Do” by Pam Tillis, and “Highway 20 Ride” by the Zac Brown Band. It’s unclear what Vendler would make of the exercise, but Pence concludes, among other things, that the very act of such analysis “shifts the focus from viewing popular country lyrics as irrelevant, free-formed, and vapid toward recognizing historical and literary connections. Songs and poetry … share a history that transforms contemporary writers’ words into art.”

Still, from the time of Homer to the Renaissance, poetry and song were inexorably linked. Because of this shared history, Pence’s anthology argues, much of the poetic tradition remains embedded in popular song. To demonstrate, Pence herself, in an essay titled “The Sonnet Within the Song: Country Lyrics and the Shakespearean Sonnet,” compares the structure of several hit country songs to that of the traditional sonnet. Citing the present-day grande dame of poetry criticism, Helen Vendler, Pence identifies the crucial element of a Shakesperean sonnet not as its rhyme scheme, metrical pattern, or line length, but rather its tight rhetorical structure, which features a progression and complication of a specific argument; a coda, or twist, at the end; and an emotional or psychic change in the speaker. Using these criteria, she analyzes “On the Other Hand” by Randy Travis, “Don’t Tell Me What to Do” by Pam Tillis, and “Highway 20 Ride” by the Zac Brown Band. It’s unclear what Vendler would make of the exercise, but Pence concludes, among other things, that the very act of such analysis “shifts the focus from viewing popular country lyrics as irrelevant, free-formed, and vapid toward recognizing historical and literary connections. Songs and poetry … share a history that transforms contemporary writers’ words into art.”

If the argument of The Poetics of American Song Lyrics is that songs and poems share an historical and literary lineage, part of the anthology’s purpose is to help make the study of song lyrics an academic discipline, á la poetry. The first essay in the book, in fact, is not an essay at all, but rather remarks that Tennessee Senator (and former University of Tennessee President) Lamar Alexander made on the floor of the U.S. Senate after Johnny Cash died. Referring to an obituary in The New York Times that labeled Cash “the foremost poet of the working poor,” he asked, “Why did we wait until Johnny Cash died to think of him as one of our ‘foremost poets’?” Alexander went on:

John R. Cash is not the only overlooked poet who ever lived in Nashville. Bob Dylan, Johnny’s friend, once said that Hank Williams was America’s greatest poet. At last count, there are several thousand Nashville songwriters struggling to write poetry, some of whom will produce lyrics that one day will be sung and remembered everywhere in the world.

If Vanderbilt University is such a center for literary criticism, then why has Vanderbilt not done more about the literature that is country music? Or why does Belmont University in Nashville or the University of Tennessee or University of Memphis not do it? Why have we waited for outsiders such as The New York Times and Bob Dylan to tell us that Johnny Cash and Hank Williams are among the foremost poets in the world? Why didn’t some scholar living right among them tell us?

Pence has not only heeded Alexander’s call, she has upped the ante: where Alexander is concerned with the poetry in country music, The Poetics of American Song Lyrics claims the whole of popular lyric as worthy of academic study. The genres addressed by the anthology’s nine theoretical essays and fourteen case studies include country, blues, rap, hip-hop, rock ‘n’ roll, and whatever genre Leonard Cohen falls into. Case studies include Cohen, Sam Cooke, Springsteen, Otis Redding, Dylan, Kris Kristofferson (in an astoundingly astute short essay on “Me and Bobby McGee” by the poet David Daniel, in which he reminds us that “[g]reat art in any form doesn’t answer questions; it enacts them”), and Cash. Beyond those usual suspects, there are also essays on Magnolia Electric Co., Caroline Herring, and Okkervil River, as well as two on R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe.

Pence has not only heeded Alexander’s call, she has upped the ante: where Alexander is concerned with the poetry in country music, The Poetics of American Song Lyrics claims the whole of popular lyric as worthy of academic study. The genres addressed by the anthology’s nine theoretical essays and fourteen case studies include country, blues, rap, hip-hop, rock ‘n’ roll, and whatever genre Leonard Cohen falls into. Case studies include Cohen, Sam Cooke, Springsteen, Otis Redding, Dylan, Kris Kristofferson (in an astoundingly astute short essay on “Me and Bobby McGee” by the poet David Daniel, in which he reminds us that “[g]reat art in any form doesn’t answer questions; it enacts them”), and Cash. Beyond those usual suspects, there are also essays on Magnolia Electric Co., Caroline Herring, and Okkervil River, as well as two on R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe.

But the real stunner in the collection, an essay that literature and writing classes alike could spend a semester studying, is a tour de force by the poet Kevin Young called “It Don’t Mean a Thing: The Blues Mask of Modernism.” In placing the blues, especially blues lyrics, at the center of the Modernist movement, Young’s essay—with its voice, breadth, cynicism, idealism, pragmatism, weariness, guts, and sheer writerly virtuosity—is itself an enactment of the blues, not only how the blues are “defiant and existential and necessary,” but how they also “reveal and revel in all our holy and humane contradictions.” Young goes on:

When [W.C.] Handy wrote down the first blues lyrics, he was capturing the common oral culture of African Americans, the “floating verses” that amounted to a shared store of imagery, one as allusive and elusive as The Waste Land, published years later. “I hate to see the ev’nin sun go down”: even the iconic first line of the song looks west, and ahead to the “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” with its evening sky “like a patient etherized upon a table.” Could hindsight as second sight help us recognize that the love song Prufrock proffers might indeed be a blues? … Years later when Eliot placed black song in his Waste Land, “sampling” James Weldon Johnson, the emergence and merging of modernism–our Shakesperean rag—was complete.

Who wouldn’t want to be in that class? There’s little doubt that students would flock, as Pence says they already have at Belmont, to a course on the literary study of popular music lyrics. The Poetics of American Song Lyrics would make excellent reading for such a course. It also just makes excellent reading.