Paradise Lost

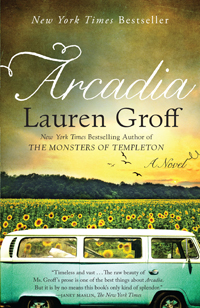

Novelist Lauren Groff talks with Chapter 16 about her acclaimed novel Arcadia

Included on countless “best of” lists in 2012, Lauren Groff’s gorgeous second novel, Arcadia, is a loving and lyrical story of the rise and fall of a commune from the late 1960s through the end of the twentieth century. It is also the coming-of-age tale of Ridley Sorrell Stone, known as Bit, the first baby born to Arcadia’s founders, the Free People, as they are putting down roots for their community in western New York.

Miraculously tiny at birth, Bit matures into a gentle, deeply empathic individual, beloved by his fellow Arcadians and an embodiment of the community’s purest intentions, which have shaped his identity. When Arcadia’s center can no longer hold against pressures from outside and within, Bit is also challenged, forced to learn the ropes of life “Outside,” as he’s always known it, amidst great and terrible social upheaval.

Miraculously tiny at birth, Bit matures into a gentle, deeply empathic individual, beloved by his fellow Arcadians and an embodiment of the community’s purest intentions, which have shaped his identity. When Arcadia’s center can no longer hold against pressures from outside and within, Bit is also challenged, forced to learn the ropes of life “Outside,” as he’s always known it, amidst great and terrible social upheaval.

Groff has acknowledged the assiduous research, both primary and secondary, that went into her third book. (She is also the author of a story collection, Delicate Edible Birds, and another novel, The Monsters of Templeton, which was a finalist for the Orange Prize. Research, she told The Rumpus, involved “following the gleam into the dark.” Groff devoured the literature of utopias and paid visits to sites where communes once flourished: the Oneida Community in New York and The Farm in Summertown, Tennessee, proved especially useful in triggering her vision of Arcadia.

But as Groff has explained, her own doubts and fears, as well as her rocky passage into motherhood—she was pregnant with her first son while writing Arcadia and characterizes herself as “a terrible pregnant person, the opposite of radiant”—also helped carve this book’s path. “Bringing a child into the world,” she told The Rumpus, “is such a terribly fraught ethical problem. We don’t need the pressure of one more person on the Earth; why would I bring a baby into a world with a future that’s so clearly barreling toward disaster?” Reading about “the wild-eyed visionaries who willfully step out of the world they disagree with, who put everything on the line to breathe life into their vision of a better world,” she said, “tugged me out of the pit. I loved their utopian projects even–especially–when they failed, because I began to see the tremendous beauty in the hard work and hope they poured into their visions, no matter what the end-result was.”

Tremendous beauty—the evidence of hard work and hope—exists, too, in the pages of Arcadia, which Kirkus called “an astonishing novel, both in ambition and achievement, filled with revelations that feel inevitable in retrospect, amid the cycle of life and death.” Arcadia is a book to be savored at the sentence level, the sounds and smells and foods of its world all brought to life in lush language that evokes both the magical realm of the Grimm tales that so deeply charge Bit’s imagination, as well as the natural world that envelops Arcadia.

Tremendous beauty—the evidence of hard work and hope—exists, too, in the pages of Arcadia, which Kirkus called “an astonishing novel, both in ambition and achievement, filled with revelations that feel inevitable in retrospect, amid the cycle of life and death.” Arcadia is a book to be savored at the sentence level, the sounds and smells and foods of its world all brought to life in lush language that evokes both the magical realm of the Grimm tales that so deeply charge Bit’s imagination, as well as the natural world that envelops Arcadia.

Prior to her reading at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Groff answered questions via email:

Chapter 16: Stephen and Ida May Gaskin’s commune in Summertown, Tennessee, provided some inspiration for Arcadia—and indeed, one of the characters in the novel goes off to start a midwifery school in Tennessee. How did The Farm influence your vision for the book’s setting?

Lauren Groff: I had talked to a number of people who had lived in intentional communities during my research phase for the book; I had also, of course, read many books—philosophical, historical, and otherwise—before I went to visit The Farm (and Oneida, which had an equal influence on Arcadia). My visit to The Farm, however, was what crystallized and formed the shape of the book within me. The landscape is so peaceful, and the people who have lived there—and who live there now—are so passionate and smart and generous that, in a very real way, I wrote the book as a loving response to the nobility of their enterprise. I would live at The Farm, if I could.

Chapter 16: One thing, among many, that I love dearly about your characterization of Bit is his deep connection to and sense of wonder about the natural world, its cyclical patterns and tensions. In a favorite passage, he notes that nature’s “rhythm is so different from my own, both more nervous and more patient.” Does this quality have an analog in your own experience of growing up, of experiencing the outdoors?

Groff: Inasmuch as a childhood set in the middle of a small and perfect village can be called semi-feral, mine was. My parents barely saw me in the summer—I was a kid with the shock of sun-whitened hair and scabby brown legs who ran around in a bathing suit and shorts I barely ever changed, with some saucy paperback I was far too young to read. I spent all day hiking, swimming, or nestled in some tree, reading, all of which is good training to notice the minute changes that occur from day to day in any given season. Bit’s love of nature is my own.

Chapter 16: Arcadia is in part about place and how place informs people, whole trajectories of lives. As a reader, are there any books that are especially important to you in which setting functions as a character itself, a primary agent of transformation?

Groff: My first self-directed reading list was full of the Gothic and the Romantic, and place is of paramount importance in both. I love Faulkner’s sweaty, wild Mississippi, I love Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s sultry and magical Macondo, I love Marilynne Robinson’s spooky Fingerbone; I love Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre and about a billion other books and authors that turn places into characters.

Chapter 16: You’ve mentioned that you have melancholic tendencies. As one all too familiar with that turn of mind, I wonder how it affects your writing. Does storytelling offer a kind of respite or retreat from your own mind, or is it more complicated than that?

Groff: I’m hardly the expert on melancholy, even my own, but I would say that it’s difficult to put any kind of sadness into a nutshell. I’d say that storytelling is the way that I cope with being a profoundly flawed human being in our particular epoch, in this terrifying world. It’s so complicated and fraught with contradiction that I would need to write another book to give a more complete answer than that, I’m afraid.

Chapter 16: “The very best thing you can do for my work-in-progress,” you once told <cite, “is to buy me a pair of running shoes.” I wonder if you might comment a little more fully about the role of exercise in your own creative process.</cite

Groff: I tend to overthink everything. This is a problem when you’re writing fiction, because the best fiction is not just cerebral, it’s also visceral. When you write from the brain, in one fell swoop you abolish the mystery necessary in creating real and breathing books. Running and swimming are ways that I handle this—because it’s very difficult to write while you’re exerting yourself physically, it makes you release any pretence of control, and after a while you stop thinking at all. That’s when the subconscious kicks in, which is really where all of the good work is done, anyway. This way you sidle up to your work, letting it know that you want to be its friend, without raising its hackles by direct confrontation. Naps are equally important.

Chapter 16: You’re raising two young boys while writing (and publishing, and promoting) novels, but I know that reconciling writing and motherhood can be tough, even heartbreaking work. For you, what makes balance possible?

Groff: For balance you need…a functional inner ear? In truth, I’m the last person on Earth who should answer this question because I don’t do any of it easily or well.

Chapter 16: In an interview with BookPage, you said, “The architecture of fiction is one of the most urgent things for me. I have to find those parallel resonances between structure and story; I have to know the story inside and out before I know the shape of the house around it.” Could you perhaps tell us how this process is playing out in what you’re working on now?

Groff: I could tell you about the story I’m working on now, but then you’d have to swim with the fishes. My work is so ugly and tender and impossible in the early stages that talking about it in any way shrivels it into a black, slimy wad. Even my husband doesn’t know what I’m working on for a few years until I hand him a mostly-finished project. In general, though, I work and work and work, I throw everything out, and then after a few years, after I know the story as completely as I could, including the 98 percent that will never appear in the book, and I suddenly find that my sentences have started to accumulate. It is a terrifying truth that having written a book (or three) does not guarantee that you’ll ever know how to write another one. You just put your head down and work and try to have both patience and hope. Writing is utopian, in its own way.

Lauren Groff will read from and sign Arcadia in Nashville on March 22 at 4 p.m. in Buttrick Hall Room 101 on the Vanderbilt University campus. The event is free and open to the public.