A Very Close Deal

Novelist Jay McInerney and editor Gary Fisketjon have been collaborating on books—and drinking Jack Daniel’s together—for the last thirty-nine years

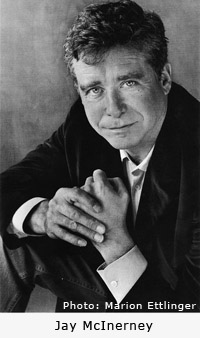

Acclaimed author Jay McInerney is most noted for his many novels, including Bright Lights, Big City and The Last of the Savages, but he is also a masterful writer of shorter works of fiction and nonfiction: his newest story collection, How It Ended, was named one of the ten best books of 2012 by The New York Times. McInerney is the wine columnist for The Wall Street Journal, work for which he won the 2006 James Beard MFK Fisher Award for Distinguished Writing. He has published three collections of essays from the column, including The Juice: Vinous Veritas, which will be released next week in paperback.

Legendary Knopf editor Gary Fisketjon was a classmate of McInerney’s at Williams College who later revolutionized the publishing business with the creation Vintage Contemporaries, the first trade paperbacks. In addition to McInerney, he has edited a host of internationally acclaimed authors, including Raymond Carver, Annie Dillard, Richard Ford, Patricia Highsmith, Cormac McCarthy, Haruki Murakami, Richard Russo, Donna Tartt, Gore Vidal, and Tobias Wolff. He lives part-time in Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee, outside Nashville.

Legendary Knopf editor Gary Fisketjon was a classmate of McInerney’s at Williams College who later revolutionized the publishing business with the creation Vintage Contemporaries, the first trade paperbacks. In addition to McInerney, he has edited a host of internationally acclaimed authors, including Raymond Carver, Annie Dillard, Richard Ford, Patricia Highsmith, Cormac McCarthy, Haruki Murakami, Richard Russo, Donna Tartt, Gore Vidal, and Tobias Wolff. He lives part-time in Leiper’s Fork, Tennessee, outside Nashville.

McInerney and Fisketjon will appear together on April 7 at the Nashville Public Library’s main branch in a program for the Nashville Writers Circle, hosted by John Seigenthaler and William M. Akers. McInerney and Gary Fisketjon spoke by phone with Chapter 16—Fisketjon from his home in Leiper’s Fork, outside Nashville, and McInerney from his home in the Hamptons.

[Editor’s note: this is the gently edited version of Stephen Usery’s podcast interview with Fisketjon and McInerney. To hear the podcast, click here.]

Chapter 16: First I want to ask you about the Writer’s Circle event, and then we’ll move on to more general matters.

Fisketjon: Cool.

McInerney: Unfortunately we don’t know too much about that. We don’t understand much at all. We were hoping you could tell us something.

Chapter 16: I just know that Siegenthaler and Akers are running it. Have you talked to Adam Ross to see what he did at his event last year?

Fisketjon: Yeah, I talked to him when he did it. Jay and I have both talked to John before for his program [Nashville Public Television’s A Word on Words], so I think it’ll be a walk in the park.

Chapter 16: Have you agreed to what stories you won’t tell about each other?

McInerney: God knows there’s a lot of them. We’ve been working together since—first we were at Williams together, and then we traveled across the country together in a Volkswagen after we graduated. Eventually Gary got me a job as a manuscript reader at Random House. And then I sent him my first novel after I wrote it. Actually, I was in the graduate program in Syracuse University, studying with Raymond Carver at the time. So we go pretty far back.

Fisketjon: I’ve been editing Jay for thirty-eight years or something.

Fisketjon: I’ve been editing Jay for thirty-eight years or something.

McInerney: We haven’t really planned this yet, but I think we’re just going to kind of wing it.

Chapter 16: Jay, you’ve written about how wine can be a mnemonic. Do you remember the first bottle of wine you two split?

McInerney: For many, many years, we just split bottles of Jack Daniels because that was our drink.

Fisketjon: Yeah, the occasional beer, a lot of whiskey. I think around the publication of Bright Lights, we would have been drinking some wine by then.

McInerney: Yeah, we were drinking, like, Châteauneuf-du-Pape then. We’ve since shared a lot of Oregon Pinot Noir because that’s where Gary is from, and I visited wine country in Oregon back in ’96 and fell in love with some of those wines. So, we tend to drink those when we’re together. Beaux Frères, for instance. And Cristom. Boy, that first bottle of wine, it’s lost in mist, I’m afraid.

Fisketjon: I’m sure there was some wine drunk at Williams.

McInerney: Yeah, yeah. But that’s usually what you did when you were trying to woo a girl, as opposed to hanging with your buddies.

Fisketjon: Yeah, right. I think wine was probably somewhat frowned upon.

McInerney: Yeah. I think it was.

Fisketjon: Why not have a real drink?

McInerney: We agreed on bourbon, though. Gary, do you remember? We visited the Jack Daniels distillery on our cross-country trip.

Fisketjon: Yeah, that was one of the highlights.

McInerney: That was a pilgrimage. Of course, we were very disappointed, as everyone is, to discover that it’s in a dry county, so we didn’t actually get to drink any Jack Daniels there.

Chapter 16: But they allow you to buy it now at the distillery.

McInerney: Well, that’s good.

Chapter 16: They’ve changed the law there.

McInerney: I mean, we made lots of pilgrimages. We went to Faulkner’s house in Oxford, Mississippi. And we somehow ended up in the jail that night. How did we get arrested, Gary?

Fisketjon: No, we didn’t get arrested; we were just asking for it. The great adventure in Nashville was getting ripped off by somebody who was giving us a very special deal at a far grander hotel than we could afford.

McInerney: Oh, right, yeah.

Fisketjon: So we made the deal, and then Jay turned around and said, “We’re never going to see that guy again, are we?” And I said, “I don’t think so.”

McInerney: Yeah, a guy we met at a bar who was going to get us a great deal on a hotel room. We made a pilgrimage to Nashville to look for—well, for us, country music meant Waylon and Willie and Kris Kristofferson [but] they had had probably decamped from Nashville by then.

Fisketjon: Yeah, there was no sign that we could find, and this guy was a very bad guy.

McInerney: Yeah, Nashville did not make a good impression on us the first time we went there. We ended up staying in this fleabag, and I got up in the middle of the night trying to find the bathroom down the hall, and there was some guy wandering around with a shotgun out in the hallway.

Fisketjon: It was the same guy who checked us in. He was kind of an all-purpose employee. That place was called the Bijou; I can’t remember where the hell it was. But then [years later] Jay kind of led the way back to Nashville.

McInerney: Yeah, strangely enough, then I met a Nashville girl in New York, and we eventually got married. I ended up buying a farm outside of Franklin. That was how Gary got here.

Fisketjon: And that’s how I got my wife.

McInerney: We introduced him to his future wife, and now he has a place outside of Franklin.

Chapter 16: Y’all were pretty much on the vanguard of leading the elite down to Nashville and all the press it’s gotten recently for being the “it” town of the year.

Fisketjon: Yeah, incredible—a front-page story in The Times.…

McInerney: Yeah. Nashville Cats!

Chapter 16: So, Jay, you’ve been on Gossip Girl; are you going to be on Nashville, as well?

McInerney: Well, I’m waiting for the call. I’m a member of SAG now, got my acting chops. I was on Law & Order last fall, so who knows? I don’t know; I’d have to work on my accent to get on that show, I think.

Fisketjon: I haven’t even seen the show.

McInerney: Playing a drunken writer from New York comes easy, but I don’t know if there’s a role that naturally suggests itself in Nashville.

Fisketjon: Yeah, I think that they’re probably not looking for any kind of writers at all.

Chapter 16: Well you could play a drunken writer coming in from a magazine to do a celebrity profile, like you’ve done with Julia Roberts.

McInerney: Yeah, that’s a good idea.

Fisketjon: Profile one of the stars.

McInerney: Suggest it to those people.

Chapter 16: Of course, they would show you up.

McInerney: Yes, they would. Well, that’s fine. It’s just acting.

Chapter 16: You’ve known each other now, what, thirty-eight years?

McInerney and Fisketjon, simultaneously: 1974.

Fisketjon: So it’s been like thirty-nine.

McInerney: That’s scary. God. Yeah, thirty-nine. We were both about eighteen when we met. Nineteen.

Chapter 16: When your book came out, Jay, how did the friendship and the editing process work together there at the beginning?

McInerney: Well, the editing process worked really well because—

Fisketjon: We’d had a lot of practice by then.

McInerney: We had been trading books and taking the same English courses. When I discovered something I liked, I’d give it to him and vice versa. And he’d been reading my stories for quite a while before I handed Bright Lights, Big City to him. So that was pretty natural, you know? What neither one of us could have predicted was this sort of phenomenon of Bright Lights, Big City after it was published. Kind of disorienting, I think, for both of us. I mean, mostly it was good, but there were points where it became too much of a good thing. But the editing process has always been pretty good. We fight a lot about stuff, but in a good way.

Fisketjon: Yeah, I think we both adhere to the rule that when there’s a disagreement, the writer always wins because it’s his book.

McInerney: Yeah, I get the veto.

Fisketjon: He gets a loaded vote.

McInerney: I would be loathe to publish a book with somebody else. It seems to be working after all these books. At this point sometimes, we can be sitting down in front of a manuscript, and he can start say something, and I can just say, “Yeah, you’re right,” before he’s even finished.

Chapter 16: Do you hear his voice while you’re drafting?

McInerney: Sometimes, yeah. Yeah, him and Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff. But I submit to Carver’s voice when my language is getting a little overblown. And sometimes Gary’s. I definitely hear it after the fact because we always have pretty intense editing sessions. We usually do some of it in person. He comes and camps out with me for a few days or vice versa.

Chapter 16: Is it OK now if your prose runs purple when you’re writing about wine?

McInerney: Well, I hope it doesn’t. There’s nothing worse than purple prose about wine. I deliberately try not to do that. Wine writing, so often, veers toward the pretentious and overblown, and the whole reason I went into it was to try to give it a fresh take and knock down some of the cobwebs and come with the new way of talking about wine. Ideally it’s not purple.

Chapter 16: Gary, have you found a new way to talk about editing?

Fisketjon: No, I really haven’t ever changed my mind. I mean, all an editor does is read something more carefully than anybody else, than any other sane person would ever contemplate, because that’s the job. It’s not so much that the writer sets the bar, but the book sets its own bar. And you’re looking for anything that falls short of that, and point it out. And it also helps the editor/publisher understand the book better than anyone would if you just read it quickly and sort of say, “Well, that’s all right. We could change that name or something.” That’s useless. But if you get into the DNA of a book, you’ll understand how it works and what it does best. So it eventually turns into a long, kind of neat conversation with me scribbling all over the pages and then sending it off. And what we discuss is where my handwriting is not legible, where what I was suggesting doesn’t make sense. But I get all of my say, and it leaves me to put anything that I notice, I’ll comment on. That has never changed.

McInerney: He’s not shy.

Fisketjon: It hasn’t gotten any faster. It more or less takes an hour to get through five pages. I do a little copyediting, but I’m probably one of the world’s mediocre copyeditors. But by the time it gets to a proper copyeditor, it’s been gone over very carefully, so there’s not a lot of loose ends. That way the copyeditor isn’t distracted by all sorts of issues that should have already been dealt with. That hasn’t changed and never will. I think that’s important. If the editor doesn’t read a book carefully, it’s a very bad omen.

Chapter 16: Now, when you’re considering taking on a new writer, is there a common feeling that you get when you’re reading their drafts, or does it always feel different?

Fisketjon: Well, it’s all going to be different because all books are different. All writers are different. It’s being able to hear something that you really like and is really good. I don’t take on things that are works in progress or “promising.” It has to be farther along than that because not only the editing but just the whole process of publication is extremely laborious, and you wouldn’t enjoy a lot of what you have to end up doing over a period of a couple of months to edit a book and then half a year or more to publish the book.

You have to believe in that book very completely to be a proper advocate for it. And I think it behooves any proper editor not to be looking for what isn’t there. Every writer’s different, and I don’t, certainly, have a style of editing—because a good writer dictates the style, and all you do is buy into it. So it’s always different, but it’s always a wonderful shock of recognition when you find something you really like because most of the stuff that you read isn’t really very good or certainly isn’t for you, for your taste. So it helps to find something new every so often just because it widens the pool, as it were.

Chapter 16: A couple of your more recent acquisitions, Adam Ross and Martin Clark, are two of my favorite writers that have come out with new stuff here in the past few years. What is it like to find the new voice? What’s the feeling you get when you find that voice?

Fisketjon: Well, it’s very exciting because you want to be optimistic, but—I don’t know how many new writers’ work I look at over the course of a year but hundreds and hundreds and hundreds. And ninety-nine times out of a hundred you’re going to say, “Thanks, not for me.”’ When you can actually say, “Yes, this is for me,” it’s quite a wonderful feeling. I think in almost every instance the people I’ve published have become friends to one degree or another. Jay’s the most longstanding of any friends I’ve got, but it’s a very close deal, and I see myself as a writer’s advocate within the publishing company. Writers have advocates in their agents, of course, but I’m the only person who’s at Knopf—or wherever the hell I was—so you get very invested in books, and since the odds of a success, much less a success like Bright Lights, Big City, are so slim, you get a lot of disappointment. But it’s a common cause, and therefore editors and publishers have many opportunities to be depressed because things don’t go as well as they should.

Chapter 16: And, so, does the wine and the Jack Daniel’s help assuage that?

McInerney: Well, they’re known to.

Chapter 16: Now, y’all were roommates for a while in New York, weren’t you?

Fisketjon: Yeah.

Chapter 16: Was there a quirk that bothered you intensely about the other person?

McInerney: Well, Gary’s quite neat, and I’m quite messy, so that was—

Fisketjon: He could trash an apartment all by himself in a matter of an hour—

McInerney: So there was that friction. But otherwise we had a lot of good times.

McInerney: Fortunately, we kept the same hours, which were night-owl hours, and we had some really good parties at this loft that Gary had in East 5th Street that I would often—summers when I was in graduate school, I would be in residence at East 5th Street, and we would have some crazy parties. And, in fact, that apartment was where I wrote the first page of Bright Lights, Big City. I came home one night about five in the morning, and I just jotted down those lines that survived intact and that I found again later in a drawer. It was a cool apartment, but the East Village is very—I mean, it was really dicey back then. This was—what was this, Gary? Like ’81 and ’82?

Fisketjon: Yeah, along in there.

McInerney: It was definitely pre-gentrification. You had to have your wits about you when you came home late at night. But it was great. Gary had gotten me a job reading manuscripts at Random House. I had an office and everything. We’d usually get up to the office around the crack of 10:45 or so.

Fisketjon: I think I would get in a little earlier. But it was a good time to be coming to New York when we did. I came in ’78 and Jay a little bit later, but it was still kind of an affordable place back then in comparison to what it’s become.

McInerney: Yeah, young people who were interested in publishing or the arts could still find apartments. And margins. I mean, the margins—the fringes—have almost disappeared now in terms of the island of Manhattan. But yeah, there was great music. We lived down near CBGB’s. We heard a lot of good stuff; we heard the Talking Heads, and—

Fisketjon: There were just all sorts of interesting people passing through then, and clubs where you could hear people you really liked for not much money at all.

McInerney: And there was this whole explosion in terms of painting and people. We had Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring in the apartment at some point, like for one of our parties. It was just a great time, but it was a much grittier time. New York was dirty, and it was dangerous, and there was a heroin epidemic and—

Fisketjon: And a lot of people who had been put out of asylums—

McInerney: Yeah, there was that big wave of deinstitutionalization. There was this law passed in ’79 or ’80 which pushed a lot of lunatics onto the street. It was an interesting time. Back then, when you heard someone talking to themselves on the street, it wasn’t because they had a cell phone.

Chapter 16: So what does the city feel like now with so much of the creative energy moving over to the Brooklyn area?

McInerney: The trouble with that is—the whole idea of a bohemia is that creative energy is sort of centralized somewhere. And, for a while, that seemed to be quite a bit the case. Maybe for a hundred years in downtown New York, you know, whether you talk about the early-twentieth century in Greenwich Village with artists and writers, or our time in the late ’70s and ’80s. The East Village, to some extent the Lower East Side, even SoHo—these downtown neighborhoods that weren’t much wanted by anyone else—became bohemias. They became communities of people who were interested in the arts or people who wanted to open galleries or nightclubs, but the trouble with Brooklyn is that Brooklyn is a little bit of a diaspora. People are spread all over the damn place. There was a moment when Williamsburg seemed to be the center of it all, but—I really wish them well over there—but I’m too old to move to Brooklyn.

Fisketjon: Yeah, we’re way too old for Williamsburg.

McInerney: I suspect Gary feels the same way.

Fisketjon: It’s a great place to visit, but. The great thing is the bookstores out there. There are some new bookstores out there that are really terrific, and some that have been around for a while, so it’s certainly a cool place for book events. In Manhattan the rents are ridiculously expensive, and margins for bookstores are very tight, and there are some good stores, but you can’t fit more than forty people in there. And in Brooklyn you have a lot more room to play with. But if there is such a thing as a Brooklyn writer, I’m not necessarily his or her biggest fan. I don’t buy into it really.

McInerney: Manhattan will always be Manhattan, but the problem with gentrification is that—I just don’t think Manhattan is as diverse as it was when we moved there.

Fisketjon: No, certainly not.

Chapter 16: How do you think the change to your work—Jay, with your writing and Gary with your editing, now that you write outside of an urban area or you edit in rural Tennessee—how do you think that change of energy in those locations affects your work?

McInerney: Well, I still spend the majority of my time in Manhattan, or at least half my time, and I still love it. But I think that my focus and my characters and my stories have changed along with me and my friends. I still write about Manhattan, and I still write about life there, but my characters have—

Fisketjon: Tend to be a bit older.

McInerney: They’ve gotten older, they’ve had children, they’ve done the things that me and my friends have done. I would scoff at the idea that I’m at this point any kind of authority on New York night life, say, or that I have my finger on the pulse of what twenty-year-olds are thinking. That would be ridiculous of me to pretend that I do. I’m continuing to write about New York and my generation as they get older there. It’s a very different New York from than we first discovered in the ’80s, for sure, but I wouldn’t want to be living the same kind of life that I did thirty years ago. It would be inauthentic. I wouldn’t want to keep trying to rewrite Bright Lights, Big City or Story of My Life because that would be inauthentic, too.

I look forward to those books by the twenty-year-olds because I think there’s a sort of dog whistle you can only hear when you’re in your twenties. There’s a way in which the young sort of catch the music of the zeitgeist, and I like to hear it. But likewise, I think in some ways, I like what I’m writing now at least as much as I did then because I actually know more about the world than I did then. Bright Lights, Big City is around two hundred pages, and that was pretty much everything I knew about the world up to that point. I put all my best stuff in, and that was it. Now I think I know more, and I know more about people, and I’m wiser in a way that may show up in my next novel.

Chapter 16:: And when might we expect a next novel?

McInerney: Funny you should ask that. It keeps getting longer and longer here—I just spent most of the day, since nine o’clock this morning, working on it. I’m hoping to give Gary something in probably June, I guess. I mean, a manuscript. As Gary knows, that’s not the end of the process. Then he gives me his thoughts, and I let it marinate for a while, and then I go back and I inevitably will write another draft. This one has just turned out to be quite long, though. The next time I’m just going to take a page from my friend Julian Barnes’s book and try to come up with a really good idea for a hundred-page novel. That would really be so great.

Chapter 16:: I love a short novel myself, as a guy who talks to authors all the time.

Fisketjon: Yeah, it makes your job easier.

Chapter 16:: Well, Gary, how does working out in the sticks agree with you?

Fisketjon: It’s great because there are fewer distractions. For real, serious editing, I’m bound to try to do as much of that as possible in Tennessee because people aren’t coming by the office, and you don’t have to take people out to lunch, and you don’t have all the office stuff getting in the way. Distraction is an editor’s biggest foe, really, because you have to put yourself into the world of each book you’re working on and stay there. So, it’s a godsend for me and has been from the start. Jay’s always liked New York a lot more than I ever have. I’m happy to be there half the time, but if I’m there for more than two weeks, I start getting anxious, just because it’s easier by far to get serious work done down here.

Chapter 16:: Which writer do you have a book coming out with next?

Fisketjon: Well, I’ve got novels from Steve Yarbrough; from Dennis Bock, a really good Canadian; a phenomenal book by Julian [Barnes] that will publish in September.

McInerney: Julian, he just sent me the English edition, by the way.

Fisketjon: Yeah, I can’t wait to talk to you about that. It’s an extraordinary book.

Chapter 16:: Well, working with a Canadian writer and Julian and Murakami—how is it working with an author that’s presumably been edited in their home country before?

Fisketjon: Well, in many cases, you’re actually working with somebody who hasn’t been edited a ton before. And with anything in translation, of course, you’re really editing somebody else’s translation. But with Julian for several books now, when I get something, I’ll edit it immediately so he has all of my notes to go along with whatever notes the British publisher would give him. That way, he doesn’t have essentially two different versions of a book coming out. So I accommodate people, but the practice of editing varies widely from country to country. In Italy, I think, nobody’s probably ever edited a book. They just sort of pretend to have read it and take the writer out for lunch and arrange for the book to be given an award or two a couple of months later when they publish. So, I don’t publish books that I don’t edit. I’ll get around to it and adapt my schedules to other people’s publication schedules, making it easier for them to have all editorial comments at one time.

Chapter 16:: I want to know, what was up with the two-entry Tumblr that you started several years ago?

Fisketjon: Well, somebody said that you can do these things in twenty minutes or half an hour or something, and I ended up spending most of the day since I don’t like to just dash shit off and send it out into the blogosphere. I finally figured out that I could either do my job or I could fool with stuff like Tumblr, but I couldn’t do both. I’d rather do my job. So, I don’t know, maybe I’ll do another one. You’re one of the very few people who’ve ever mentioned that to me. The return on the investment, shall we say, was pretty poor.

Gary Fisketjon and Jay McInerney will appear on April 7 at the Nashville Public Library in a program of the Nashville Writer’s Circle, hosted by John Seigenthaler and William M. Akers. A reception begins at 2 p.m. with the program following at 2:30.