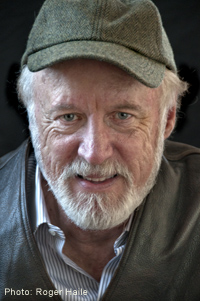

Life Among the Fallen

Allan Gurganus takes a darkly comic look at small-town life in Local Souls

The three novellas that make up Allan Gurganus’s Local Souls are all set in Falls, North Carolina, the same fictional town Gurganus fans know from his 1989 classic, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All. The Falls of Local Souls (pop. 6,803) is a decidedly twenty-first-century burg where the insular coziness of small-town life is being diminished by newcomers, digital communication, and natural calamity.

Even so, it remains a genteel village where memories are long and everyone is aware of his or her place in a social order that is distinctly narrow. Lifetime citizens of Falls tend to feel their insignificance. They worry, as one character puts it, that they have “fallen off the big-time honor-roll.” Big-time trouble, however, is something they know about. The lives in Local Souls are haunted by misdeeds and misfortunes, large and small. All three of its stories—“Fear Not,” “Saints have Mothers,” and “Decoy”—are comic, but the comedy here is biting and sometimes very dark indeed.

Even so, it remains a genteel village where memories are long and everyone is aware of his or her place in a social order that is distinctly narrow. Lifetime citizens of Falls tend to feel their insignificance. They worry, as one character puts it, that they have “fallen off the big-time honor-roll.” Big-time trouble, however, is something they know about. The lives in Local Souls are haunted by misdeeds and misfortunes, large and small. All three of its stories—“Fear Not,” “Saints have Mothers,” and “Decoy”—are comic, but the comedy here is biting and sometimes very dark indeed.

“Fear Not,” is the breeziest of the three, with an ironic, sharp-eyed narrator—a writer—who is untouched but not entirely unmoved by the story’s events. The tale is notionally structured as a stage musical, and the star is a pretty young thing known as Fear Not (and later, Fearnot—it’s complicated). When Fearnot is fourteen, her father is accidentally guillotined by a motorboat during a family outing. The boat was piloted by Dad’s best friend, who soothes his guilt by pouring out his heart to the grieving girl during long car rides. Predictably, he soon has something more to feel guilty about. Fearnot winds up pregnant, and her baby is whisked away at birth. The denouement brings a revelation that, in the telling, is funny, awful, and oddly touching.

The second novella, “Saints Have Mothers,” features a much luckier young girl named Caitlin Mulray, who was “born a somebody,” her mother, Jean, declares, “and they can do as they like.” What Caitlin likes is to do good deeds, and that’s the trouble. Caitlin’s charity knows no bounds. She lets birds, mice, and Jehovah’s Witnesses into the house. She gives her mother’s belongings, including all her shoes, to Goodwill. Jean even catches her helping a homeless drunk relieve himself against a wall. Not content with mere saintliness, Caitlin is brilliant and beautiful, as well. The whole town regards her as a paragon, but she’s hell to parent—especially for Jean, who once nursed her own dreams of being a somebody.

A not-quite-guilty resentment simmers in Jean. When Caitlin goes missing during a do-gooder trip to Africa, her aging, overlooked mama suddenly inherits her local stardom. Jean finds she glories in all the attention, and she wonders if that’s so wrong. After all, she says, “when her somebody disappears, is the mom not—as sort of first runner up—expected fill in during the missing queen’s remaining reign?” Jean opens the Pandora’s Box of maternal envy, and needless to say, things don’t turn out so well for her. The brilliance of “Saints Have Mothers” lies in how thoroughly lovable it makes the bad mother.

A not-quite-guilty resentment simmers in Jean. When Caitlin goes missing during a do-gooder trip to Africa, her aging, overlooked mama suddenly inherits her local stardom. Jean finds she glories in all the attention, and she wonders if that’s so wrong. After all, she says, “when her somebody disappears, is the mom not—as sort of first runner up—expected fill in during the missing queen’s remaining reign?” Jean opens the Pandora’s Box of maternal envy, and needless to say, things don’t turn out so well for her. The brilliance of “Saints Have Mothers” lies in how thoroughly lovable it makes the bad mother.

“I think the Lord is fastest to forgive us local souls,” says Bill Mabry, the narrator of “Decoy.” Bill sees a special virtue among the “worshipful and tied-down” citizens of Falls (or, as they like to call themselves, the Fallen). They have a happiness unknown to the ambitious ones who emigrate to the big city, and if there’s ever a hint that life might really be less than perfect, the Fallen have “the dignity to hide our doubt until cocktail hour.” Part of Bill’s love of Falls is his fierce attachment to a person: Marion “Doc” Roper, who has carefully tended the defective hearts of Bill and his father, Red. When Doc decides to retire and take up crafting arty duck decoys, it feels like a betrayal. “Where is it written that a sane, vigorous man of seventy has to pack it in?” Bill asks plaintively. Things take an even more unhappy turn when natural catastrophe strikes the town, leading to changes that break Bill’s heart in more ways than one.

“Decoy” gives the reader a taste of existential pain that is missing in the other two stories. Gurganus plays the travails of Fearnot and Jean mostly for laughs, while Bill’s troubles have a tragic edge. His life mirrors the life of Falls as a community—its happiness, its cloistered self-regard, and finally its decay. Gurganus has a lot of ironic fun with his local souls, but in the end he gives them their full human due. As the acerbic narrator of “Fear Not” notes, the same events “that overwhelm Greek dramas live on side streets paying taxes in our smallest towns.” He could be speaking for his creator when he adds, “Instead of disapproving, someone could decide, where possible, to try and love all this alive.”

Allan Gurganus will discuss Local Souls at the twenty-fifth annual Southern Festival of Books, held in Nashville October 11-13, 2013. All festival events are free and open to the public.