Troubled Revolutionary

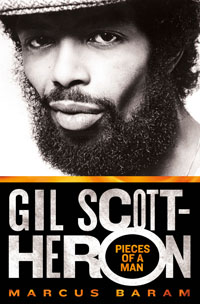

Marcus Baram’s Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man explores the life of the late artist and activist

Gil Scott-Heron’s songs and spoken-word performances, including classics like “Johannesburg,” “Whitey on the Moon,” and “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” made him America’s poet-prophet in the 1970s. Scott-Heron spoke against injustice with wit, empathy, and justified anger, and he, along with his musical partner, Brian Jackson, had a formative influence on early hip-hop and neo-soul. He shunned conventional pop stardom but nevertheless became a star, playing to large crowds and winning abundant critical praise. And then, in spite of help from friends and family, he fell irretrievably into drug addiction, saw his career nosedive, and died alone at age sixty-two. Scott-Heron’s fate seems to echo an old and oft-repeated story in the music world, but in Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man, journalist Marcus Baram delves deeply into the artist’s life and psyche, offering some insight into why this particular man went down that sorry road.

Scott-Heron was born in Chicago in 1949, the son of a Jamaican-born soccer player, Gillie Heron, and Bobbie Scott, a librarian from Jackson, Tennessee. Gillie abandoned the family completely when Scott-Heron was still an infant, and Bobbie sent the toddler to live with his grandmother, Lillie, in Jackson, where he stayed until Lillie’s death in 1960. Although Scott-Heron was certainly shaped in many ways by his teen years in New York, he always regarded Lillie—an “issues woman” who didn’t hesitate to speak up for herself in the segregated South—as a central figure in his life, and he always retained fond memories of the close-knit black community in Jackson.

Scott-Heron was born in Chicago in 1949, the son of a Jamaican-born soccer player, Gillie Heron, and Bobbie Scott, a librarian from Jackson, Tennessee. Gillie abandoned the family completely when Scott-Heron was still an infant, and Bobbie sent the toddler to live with his grandmother, Lillie, in Jackson, where he stayed until Lillie’s death in 1960. Although Scott-Heron was certainly shaped in many ways by his teen years in New York, he always regarded Lillie—an “issues woman” who didn’t hesitate to speak up for herself in the segregated South—as a central figure in his life, and he always retained fond memories of the close-knit black community in Jackson.

Scott-Heron showed an early aptitude for both music and writing, and he landed a scholarship to the prestigious Fieldston School after he and Bobbie moved to New York. He went on to Lincoln University—alma mater of his literary idol, Langston Hughes—and it was there that he met Brian Jackson and other musicians, and his unique brand of music, poetry, and social commentary began to take shape.

Scott-Heron wrote in detail about his early life in his posthumously published memoir, The Last Holiday, and it must be said that his recollections are a lot livelier and more entertaining than Baram’s rather dry report. But Baram’s account has the virtue of being more straightforward, and it seems meticulously fact-checked, as well. (For instance, it corrects Scott-Heron’s spelling of Lillie’s name.) Baram fills in details about Gillie Heron and, more importantly, he carefully traces Scott-Heron’s musical development during his Lincoln years, noting the key influence of The Last Poets, a group of black-nationalist poets who were gaining fame at the time for their spoken-word performances in New York.

Scott-Heron always thought of himself as a writer. He published two novels in his early twenties, and he earned an M.F.A. in creative writing from Johns Hopkins, despite having left Lincoln without a degree. Baram reiterates his claim that he pursued music at least in part because it was a better way to promote his ideas to a non-reading public. “Though the revolution may not be televised and may not be read,” Baram writes, “it could certainly be propelled through the sound of music.” This choice was also influenced by his reaction against what he saw as the stifling demands of both academia and the publishing business.

In any case, his early recordings with Jackson and the other members of the group they called Midnight Band quickly garnered airplay and fans, and by 1974 they were a big enough deal to attract the attention of legendary producer Clive Davis, who thought Scott-Heron could be “the black Bob Dylan.” Davis’s support, as Baram portrays it, was a mixed blessing. It gave Scott-Heron the luxuries of ample recording time and label promotion, but it meant that business concerns now intruded on the creative process. Scott-Heron disliked the publicity machine, and he particularly hated the Dylan comparison. “I’m doing something else altogether and I would guess that anyone with an adequate amount of perception would be able to dig that,” he said in a contentious 1976 Playboy interview.

In any case, his early recordings with Jackson and the other members of the group they called Midnight Band quickly garnered airplay and fans, and by 1974 they were a big enough deal to attract the attention of legendary producer Clive Davis, who thought Scott-Heron could be “the black Bob Dylan.” Davis’s support, as Baram portrays it, was a mixed blessing. It gave Scott-Heron the luxuries of ample recording time and label promotion, but it meant that business concerns now intruded on the creative process. Scott-Heron disliked the publicity machine, and he particularly hated the Dylan comparison. “I’m doing something else altogether and I would guess that anyone with an adequate amount of perception would be able to dig that,” he said in a contentious 1976 Playboy interview.

Scott-Heron’s prickliness about critical labels, which would show itself again when people started calling him “the godfather of hip-hop,” was just one manifestation of a deep-seated wariness in his personality, according to Baram. He not only disliked and distrusted anyone with power over him; he actually found it difficult to trust anyone fully, thanks in large part to the trauma of his father’s abandonment. (Gillie showed scant interest in his son even after they were reconnected in the 1970s.) Baram quotes Brian Jackson as saying that it “didn’t take much to convince him that you weren’t on his side.” The smallest slight became a betrayal in Scott-Heron’s eyes, according to Jackson: “And if you went against him, then you abandoned him.”

By the late 1970s Scott-Heron had developed a serious cocaine habit, and he later progressed to freebasing. Drugs were his escape from the pressures of the music business, and they were also a refuge from difficulties in his personal life. He had a turbulent marriage to actress Brenda Sykes that ended in divorce, as well as several on-again, off-again romances, and he had four children from different relationships. “Love is a difficult thing for me to experience,” he once wrote poignantly. As his addiction took its inevitable toll on his body, his career, and his life, he was unable to admit the seriousness of his problem or accept help from anyone, even those who cared about him deeply.

He continued to perform, and he received new attention thanks to the rise of hip-hop, but he was in no shape to work regularly, and his last years included several stints in jail for drug possession. Although he was on good terms with his children, he died alone in a New York hospital, where he apparently told the staff he had no next of kin. His daughter Gia, according to Baram, saw this as typical of her father’s self-protective pride: “Maybe he didn’t want people to see him in that weak and vulnerable position.”

Baram writes out of a profound respect for Scott-Heron. He’s a long-time fan who got to know the artist well after his glory days in the ’70s and early ’80s. The book’s abundant detail about Scott-Heron’s career will please hardcore fans but might be a bit much for those who are more interested in him as a cultural figure. Baram’s portrait is informed by interviews with many friends and family members, and it is fascinating—unsparing but never lurid. Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man is an excellent complement to Scott-Heron’s own account of his life, and it’s also a sad reminder of what a remarkable mind and spirit we lost with his death.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College, she has attended the Clothesline School of Writing in Chicago, the Moss Workshop with Richard Bausch at the University of Memphis, and the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. She lives in White Bluff.