A Literary Horror Story

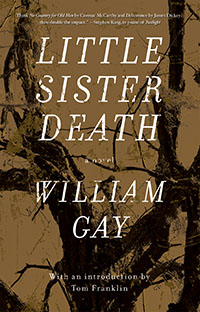

The late William Gay’s incomplete ghost story, Little Sister Death, has just been published

When the writer William Gay died in 2012, he left behind two books: the more or less finished novel The Lost Country and an incomplete draft called Little Sister Death. Both are just now being published by Dzanc Books. The Lost Country, originally slated for October 2015, is still forthcoming; Dzanc published Little Sister Death earlier this month.

The latter book is a fictional retelling of the Bell Witch legend, which revolves around a haunted farmstead near Adams, Tennessee, northeast of Nashville. According to the legend, a spirit named Kate haunted the log-cabin home of John Bell and his family; invisible, she began with noises in the walls and escalated to slaps and punches. The Bells refused to leave, and word spread; soon hundreds of people had descended on the property, taking turns talking and even shaking hands with the witch. Bell died in 1820, but the Bell Witch legend lives on, inspiring books, movies (including The Blair Witch Project), and the unsettled dreams of countless Middle Tennessee children.

The latter book is a fictional retelling of the Bell Witch legend, which revolves around a haunted farmstead near Adams, Tennessee, northeast of Nashville. According to the legend, a spirit named Kate haunted the log-cabin home of John Bell and his family; invisible, she began with noises in the walls and escalated to slaps and punches. The Bells refused to leave, and word spread; soon hundreds of people had descended on the property, taking turns talking and even shaking hands with the witch. Bell died in 1820, but the Bell Witch legend lives on, inspiring books, movies (including The Blair Witch Project), and the unsettled dreams of countless Middle Tennessee children.

Gay, who was born on Halloween, tweaks the tale a bit; he gives the legend—he calls her the “Beale” witch—something of an origin story, and he tells it from a near-present-day point of view, with a plotline about a writer named Binder, who in the early 1980s moves his young family to the house while researching for a novel on the witch. Binder is in many ways patterned on Gay himself: a struggling writer from Tennessee who spent time working in Chicago factories before moving back home.

It’s always dangerous to read too much of an author into a character, but it’s also hard not to wonder whether Binder is the writer Gay wanted to be. Gay was, in the end, more successful than Binder is in this novel, but Binder has an easier time getting published than Gay did; he also has a wife who understands and supports his art, and he’s able to scratch out a living with his words—something that Gay, until very late in his life, was unable to do.

Binder’s story is counterpointed by stories about the lives of previous occupants of the house, all of whom come to undesirable ends. Most of them are itinerant farmers and sharecroppers, and though Little Sister Death is primarily a ghost story, through these early occupants we also get a detailed portrait of farm life in Middle Tennessee during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—a period and a place that Gay, who lived much of his life in or around the town of Hohenwald, knew better than many.

Fast forward, and Binder is doing a different kind of fieldwork—not harvesting but writing, a metaphor that Gay deploys thickly but not overbearingly. In using manual labor, haunted spaces, and creeping horror as a parable for the writing process, he owes a debt to Stephen King’s The Shining. The pains of the writing process and the horror of the supernatural begin to blur; toward the end of the novel Binder sees emanations of the witch—as a dog, as a flaxen-haired girl—everywhere, but he can’t decide where they come from. When he sees the girl in a movie theater, Gay writes, “There was an eerie familiarity about her, as if she were a creation from his fantasies, from his dreams—or worse, he suddenly thought, fearing madness, from the book he was writing.”

Fast forward, and Binder is doing a different kind of fieldwork—not harvesting but writing, a metaphor that Gay deploys thickly but not overbearingly. In using manual labor, haunted spaces, and creeping horror as a parable for the writing process, he owes a debt to Stephen King’s The Shining. The pains of the writing process and the horror of the supernatural begin to blur; toward the end of the novel Binder sees emanations of the witch—as a dog, as a flaxen-haired girl—everywhere, but he can’t decide where they come from. When he sees the girl in a movie theater, Gay writes, “There was an eerie familiarity about her, as if she were a creation from his fantasies, from his dreams—or worse, he suddenly thought, fearing madness, from the book he was writing.”

Little Sister Death is unfinished, though not in the usual way. It ends abruptly, but what is there is polished prose. Gay writes in a casual but carefully deployed Southern vernacular; people don’t sit, they set. “Making” is an intransitive verb, as in: “Here he had a fine corn crop making and no one to tend it.” A person poking around a dark toolshed is “likely to get copperhead bit.”

And he’s full of wonderful turns of description and phrase. The drone of dirtdaubers is “dry nearmetallic.” An old man carving a stick leaves behind “nighweightless shavings.” A snake has a “newpenny head.” It is some of Gay’s most accomplished writing, moving far beyond the cheap gothic titillation of some of his earlier work and capturing the nuance and expert pacing of some of his best, as in the short story “The Paperhanger.”

As a novel, Little Sister Death may fall firmly into the horror genre, but fans of Gay will mostly register sadness. The book ends, suddenly and unsatisfactorily, just after a fight between Binder and his brother-in-law. Many threads are left untied, and there should be easily another hundred pages to go. Up to a point, there’s nothing to be done about that. Gay died suddenly; he didn’t have time to tidy up loose ends. But Dzanc, a relatively unknown publisher from Michigan, does readers a disservice by not flagging the book’s incomplete status. Appended to the end is an essay by Gay about the Bell Witch legend, originally published in The Oxford American, but without context, or even an introductory explanation about the essay’s significance to the novel, it’s unclear why it’s there.

But that’s not really why Gay’s readers will be sad. They’ll appreciate what they can find. The real sadness comes in contemplating what the book portends: a rapid evolution in Gay’s skills as a writer, and the likelihood that, had he not died when he did, he would have turned out ever-better fiction, a possibility only glimpsed, though quite clearly, in Little Sister Death. Fans can only hope that The Lost Country delivers where Little Sister Death could only promise.

[To read excerpts from The Lost Country, click here and here.]

Nashville native Clay Risen is the author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination and American Whiskey, Bourbon and Rye: A Guide to the Nation’s Favorite Spirit. His new book, The Bill of the Century: The Epic Battle for the Civil Rights Act, appeared in spring 2014. He lives in New York, where he is an editor at The New York Times.