An Antidote to Political Venom

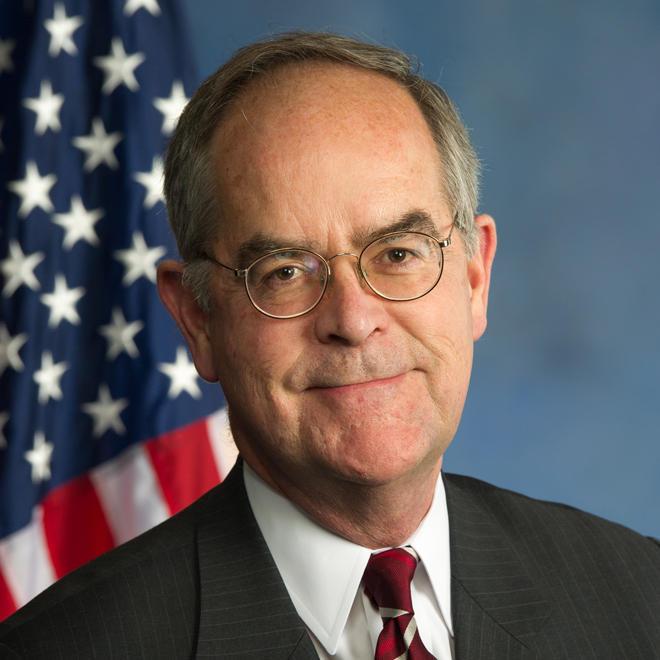

For Congressman Jim Cooper, the cure to this year’s political demagoguery is a good dose of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men

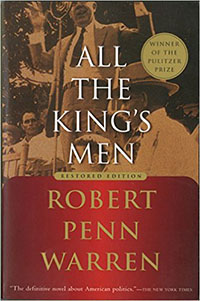

Long before House of Cards, there was a political novel that you couldn’t stop binge-reading: Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1947. Every few decades, demagogues have threatened to take control of American government; now our generation faces the threat. Warren knew such men intimately, and All the King’s Men explains the 2016 presidential election better than Netflix can.

In the novel, Warren fictionalized the meteoric rise of Huey Long, Depression-era Louisiana governor and U.S. senator. Because of his radical populism, Huey Long was said to be the only man whom President Franklin Roosevelt feared. Even after his assassination in 1935, Long was so powerful that his political dynasty lasted for most of the twentieth century: his brother Earl became governor; his son Russell became a U.S. senator, and his cousin Gillis became a congressman. If Huey himself had lived, he might well have become America’s first dictator. He preached “Every Man a King,” but he coveted the throne for himself.

In the novel, Warren fictionalized the meteoric rise of Huey Long, Depression-era Louisiana governor and U.S. senator. Because of his radical populism, Huey Long was said to be the only man whom President Franklin Roosevelt feared. Even after his assassination in 1935, Long was so powerful that his political dynasty lasted for most of the twentieth century: his brother Earl became governor; his son Russell became a U.S. senator, and his cousin Gillis became a congressman. If Huey himself had lived, he might well have become America’s first dictator. He preached “Every Man a King,” but he coveted the throne for himself.

My favorite biography of Huey Long was written by T. Harry Williams, but Warren does a better job of capturing Long’s angelic/devilish spirit with a fictional character named Willie Stark. You need poetic license in order to tell the whole truth, to create a 3-D hologram of a master political manipulator that jumps off the page. Warren won the first of his three Pulitzers for this novel. The film version won an Oscar.

The novel is dated in its use of the n-word, its dialect, its harness shops and telegrams, and the incomprehensible poverty of the Depression. But human nature has not changed at all; in fact, people proudly refuse to change. That’s why It’s a Wonderful Life and To Kill a Mockingbird remain so popular: they show people acting just like us, only wearing funny clothes. Similarly, politics—getting the talk right—is as changeless as the word demagogue itself, which derives from an ancient Greek term for leaders who crave short-term popularity. The demagogue shouts, “Your will is my strength. Your need is my justice.” This is the hiss of the serpent.

It is not fair to the novel’s Pulitzer-winning prose for readers to focus solely on its study of mob psychology, but All the King’s Men is also, unlike any other novel I’ve ever read, a first-rate instruction manual. Machiavellian insights—“It is better to be feared than loved”—are echoed by Warren without being didactic:

“Now Boss,” Tiny said, “now, Boss, that ain’t fair, you know how all us boys feel about you. And all. It ain’t being scared, it’s—”

“You damn well better be scared,” the Boss said, and his voice was suddenly sweet and low. Like a mother whispering to a child in the crib.

We have a lot to learn from Warren because the only authors today who truly “get” politics are Robert Caro and Joe Klein, a biographer and a journalist. Politicians themselves are little help: although we know how to play the game, we are poor explainers. We are like jazz musicians who can’t read sheet music. It is a miracle that Warren, a professor of English—not political science—at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University, was a composer who somehow knew all the riffs. What are some of his themes? Warren did not invent opposition research but he immortalized it:

For nothing is lost, nothing is ever lost. There is always the clue, the canceled check, the smear of lipstick, the footprint in the canna bed, the condom on the park path, the twitch in the old wound, the baby shoes dipped in bronze, the taint in the bloodstream.

Warren’s aphorisms, like “Bust ’em and they’ll stay busted, but buy ’em and you can’t tell how long they’ll stay bought,” are priceless. His paragraphs on the different phases of Stark’s career—job description of a candidate, first speech, rule of law, legislative process, dual nature of man—are worth memorizing because they are uncannily relevant today. Warren is being heralded by hard-nosed publications like The Wall Street Journal for his foresight. Not bad for a seventy-year-old novel.

Every American should read All the King’s Men, slowly and thoughtfully, before the November election. It contains an antidote to this year’s venom. Sadly, of course, the victims who need it most are least likely to read it. It takes a long time to read 656 pages, but so does watching all four seasons of House of Cards. You will be fascinated, disgusted, amused, appalled, and tearful. And you will also be cured of snakebite.

Every American should read All the King’s Men, slowly and thoughtfully, before the November election. It contains an antidote to this year’s venom. Sadly, of course, the victims who need it most are least likely to read it. It takes a long time to read 656 pages, but so does watching all four seasons of House of Cards. You will be fascinated, disgusted, amused, appalled, and tearful. And you will also be cured of snakebite.

Politicians—even demagogues—are not the true enemy. Average voters are their own worst enemies when they willingly suspend their disbelief while watching cable “news.” In a democracy, the people rule—but they can also misrule. They can also misbehave at public rallies, allowing demagogues to exploit their hatred. Voters seldom focus on the vital nature of their job, preferring to view politics as entertainment. Voters hate the truth about themselves, refusing to believe that mirrors, scales, report cards, or FICO scores are accurate. But they also look down on officeholders, believing they’re all corrupt and their jobs are easy. And it’s hard to keep good help that way.

There will always be politicians tempting us with easy answers, taking advantage of our gullibility. But they cannot lead us astray if we refuse to follow them. The old circus master, P.T. Barnum, once said, “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Because of social media and the merger of politics with celebrity, a sucker is probably born every few seconds today. The only long-term hope for democracy is a public-education system that enables enough citizens to see through the charming lies that Huey Long’s successors are telling us. Otherwise, we will be seduced into selling out America to convincing hucksters who very much want to be President.

Jim Cooper was born and raised in Tennessee. He and Martha, his wife of thirty-one years, live in Nashville and have three children. A Democrat, he represents Tennessee’s fifth district in the United States Congress, where he’s known for his work on the federal budget, health care, and government reform. He’s also a businessman, attorney, and part-time Vanderbilt professor when Congress is not in session.

This essay is part of the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a joint venture of the Pulitzer Prize board and the Federation of State Humanities Council in celebration of the 2016 centennial of the Prizes. For their generous support of the Campfires Initiative, we thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Pulitzer Prizes board, and Columbia University.