An Assault on Making Sense

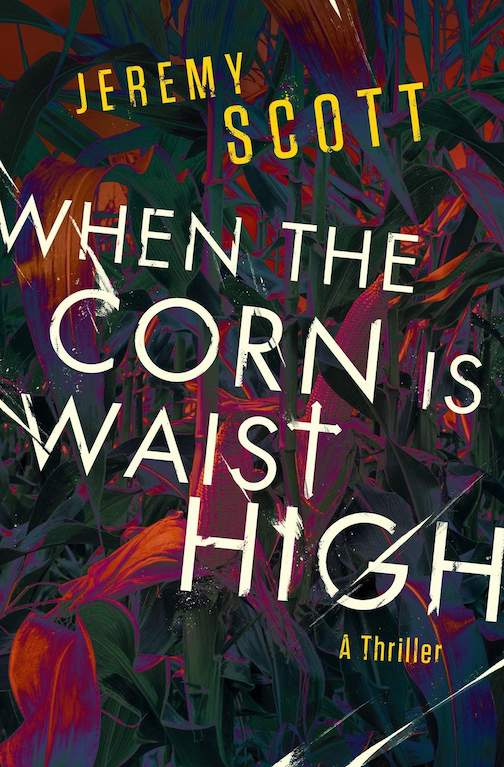

Odie Lindsey’s debut story collection, We Come to Our Senses, details the dirty secrets of deployment

From the heroic memorials of former presidents and war generals on Tennessee’s Capitol Hill to the Southern myth of gentility dictating gender roles, nothing makes sense to the characters of Odie Lindsey’s short stories. Lindsey’s debut collection, We Come to Our Senses, features people whose imaginations have been scarred by combat—or the looming threat of combat. Story after story resists the human need to claim meaning in any definitive sense, letting the attachments of family, vocation, patriotism, and companionship slip from the grasp of its traumatized characters like stray thoughts on another aimless day.

The hilltop view of Tennessee’s State Capitol—“skirted by fine landscape architecture. By granite and bronze memorial. By a sweeping, grassy mall that flows downhill like an emerald gown-train, stitched at the periphery by bulbs of antique lamplight”—features prominently in the last hurrah of a young man before he reports for boot camp. The narrator of this irreverently titled story, “So Bored in Nashville,” regrets his decision to enlist and rages against the memorials to Tennessee’s heroes: James K. Polk, Sergeant Alvin York, Sam Davis, and Andrew Jackson. Smearing fast-food condiments all over them, he calls the idyllic vista “a remembrance to, or declaration of, cataclysm.”

Vagueness of purpose leaves space for precision of detail. Lindsey populates his scenes with unsparing images, sharp enough to draw blood—or at least to stop a conversation in its tracks. In “Colleen,” for example, a female veteran barely of drinking age wanders into the local VFW bar during a story cycle of war memories and publicly confronts her commanding officer with searing detail, asking, “Was I the first? Or did you burn other girls?”

The experience of women in the combat zone and at home is a preoccupation of Lindsey’s that sets his stories apart from other war-time literature. Male veterans never miss the opportunity to revisit their trauma or to console themselves with a brotherhood that understands killing, heartbreak, terror, and torture. They believe they have every detail of war covered until Colleen gives her own blow-by-blow account of friendly fire. Many of these stories feature female protagonists. In this way Lindsey refuses to be complicit in the silencing of women’s accounts of war. The final story, “Hers,” contemplates the double discrimination of women in the military as the trauma of gender bias and sexual harassment in the field compound an ambivalent homecoming by a citizenry reluctant to embrace its heroines.

The experience of women in the combat zone and at home is a preoccupation of Lindsey’s that sets his stories apart from other war-time literature. Male veterans never miss the opportunity to revisit their trauma or to console themselves with a brotherhood that understands killing, heartbreak, terror, and torture. They believe they have every detail of war covered until Colleen gives her own blow-by-blow account of friendly fire. Many of these stories feature female protagonists. In this way Lindsey refuses to be complicit in the silencing of women’s accounts of war. The final story, “Hers,” contemplates the double discrimination of women in the military as the trauma of gender bias and sexual harassment in the field compound an ambivalent homecoming by a citizenry reluctant to embrace its heroines.

The search for one unifying narrative or unadulterated purpose both centers and decenters the lives of these veterans, male and female alike. In “D. Garcia Brings the War,” two Gulf War veterans take a detour on a Kentucky road trip to pick up a pretty young hitchhiker named Berea, but the experience revives a desire to stop the feeling of sliding “like truck tires in slop sand, slugging for traction or meaning, for anything beyond the Cause.” Berea. Lindsey writes, “is our belief that the miles and the years and the love in the books will be redeemed. That the songs and the flags will be replenished, if we can just move past ourselves, past our infidel past, and back to the Cause.”

In We Come to Our Senses, the protagonists in these stories reappear as minor characters in other stories, linking the narratives in a web of acquaintances and relationships. But none of them ever reach a final destination or find their way back to the cause, or to the grand narratives of yesterday. Instead they linger in the present moment—in the vividness of detail: beautiful, innocent, or violent—and search out some hope and honesty there.

Out of the present—of what can be seen, touched, tasted, smelled, heard—each character builds a future where “coming to our senses” doesn’t mean listening to reason or returning to consciousness. The traumatized veteran knows these states to be illusions. But in the absence of reason, and with an unreliable consciousness, meaning can be found through the body and what it knows in the here and now, even as one seeks to escape the past or fears the future.

Beth Waltemath graduated with a degree in English from the University of Virginia and worked at both Random House and Hearst magazines before leaving publishing to attend Union Theological Seminary in New York City. A Nashville native, she now lives in Decatur, Georgia.