Cold Hands, Warm Heart

Book publicist Caitlin Hamilton Summie steps to the other side of the literary desk

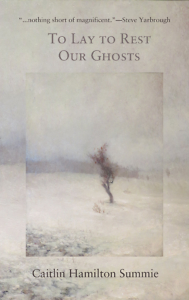

Caitlin Hamilton Summie’s debut story collection, To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts, explores the many shades of feeling between loneliness and belonging. The stories center on the complexity of family relationships with such empathy and humanity that novelist Steve Yarbrough called the book “nothing short of magnificent.”

Although each deals with some kind of loss (of ability, job, partner, or child), these stories are not existential meditations. They focus instead on human resiliency in the face of life’s most devastating moments, on the characters’ daily choice to continue reaching out to others, even during hardship.

Although each deals with some kind of loss (of ability, job, partner, or child), these stories are not existential meditations. They focus instead on human resiliency in the face of life’s most devastating moments, on the characters’ daily choice to continue reaching out to others, even during hardship.

In “Tags,” the main character, Delores, explores her own family’s loss during WWII by describing her friend Jimmy’s fixation on his father’s dog tags. Summie captures the melancholy and dread of WWII in Delores’s simple description of “Jimmy and me sitting on the curb, tired of marbles, tired of tin, him with that sound of his father, and me with nothing of mine but his name.”

Summie’s depiction of Midwestern home life is punctuated in “Tags” with understated, declarative sentences emphasizing each family’s loss. Delores describes the increasing urgency of the games the neighborhood kids play as WWII drags on: “We shot whoever played the Germans again and again and again, standing over each other, sometimes placing a foot down on a shoulder, pressing. We died for our country a hundred times.” In these devastating lines, Summie grounds readers in reality just as they become lost in her beautiful prose.

In “Brothers,” a story about a recently paralyzed twenty-something who struggles to assert his own independence, the Midwestern cold functions like an antagonist. George’s plan to defend his choice to live alone in the family’s remote cabin is complicated when his wheelchair becomes stuck in a hole in the road minutes before his brother Ephraim arrives. Ephraim helps free the chair from the hole but also takes the opportunity to urge George to consider moving back to the city.

After too many drinks before a roaring fire, the brothers begin to argue about George’s exasperation with the city: “With the noise. With crowds. With deadlines.” The tension between them builds until they are forced out of the cabin into the snow, a foil for their hot tempers, and George becomes separated from his brother. “There is only so far I can go, only so far I can follow,” he thinks—the limitations of his new life summarized in a single sentence.

After too many drinks before a roaring fire, the brothers begin to argue about George’s exasperation with the city: “With the noise. With crowds. With deadlines.” The tension between them builds until they are forced out of the cabin into the snow, a foil for their hot tempers, and George becomes separated from his brother. “There is only so far I can go, only so far I can follow,” he thinks—the limitations of his new life summarized in a single sentence.

As in the Midwestern classic Winesburg, Ohio, most of the action in To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts occurs in the minds of its introspective characters. Their emotional claustrophobia is most clear in “Motherly.” The story opens with a middle-aged woman’s observation of children skating on a frozen pond. The sight reminds her of a time when she had to lead her own daughter, whom she raised alone, through a blizzard. Her daughter’s insistence on following her own instinct in navigating the storm parallels the mother’s struggle to let her daughter live as an independent adult. Again Summie uses simple language to crystalize big moments in the story: “Jenny tugged free of my hand, and I felt the release, the sudden lightness. I reached out, but she moved around my hand, making her own way toward the fence.”

The recurrent “character” who gets the most space in these linked stories is snow. A consistent blanket of snow permeates almost every page with the quiet coldness—but not the violence—of Fargo. Snow acts as a comfort, a threat, an obstacle (and it will probably come as a relief for readers on the book’s steamy August 8th release date).

To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts does not shy from life’s hardest moments, but its sorrow is not gratuitous. Summie is a writer who approaches life as a whole, both good and bad, rooted in history and place, and her elegant prose shines in this collection.

Sarah Carter is a high-school English teacher living and working in Lebanon, Tennessee. She is currently an M.F.A. candidate at the Sewanee School of Letters.