A Friend from Chile

The seeds of a novel are sown in a friend’s disappearance

In 1970 I met a dark-haired Chilean woman with a beautiful smile and an unassuming, quiet demeanor. She was in New York for the same reason I was: our husbands had been accepted to a one-year graduate program at New York University.

We all lived in student housing in an apartment building on Washington Square West in Greenwich Village. It was an ideal location but for one drawback: when winter arrived, the maintenance personnel went on strike, and the Teamsters refused to cross the picket lines to deliver fuel. Heat and hot water were rationed in our building, two hours in the morning and two at night, but the inconvenience promoted neighborliness. We commiserated with each other. We threw parties to keep warm. I especially remember a party hosted by a Peruvian couple, at which our Chilean friend was being the ideal guest—replenishing refreshments and taking dirty dishes into the tiny kitchen.

We all lived in student housing in an apartment building on Washington Square West in Greenwich Village. It was an ideal location but for one drawback: when winter arrived, the maintenance personnel went on strike, and the Teamsters refused to cross the picket lines to deliver fuel. Heat and hot water were rationed in our building, two hours in the morning and two at night, but the inconvenience promoted neighborliness. We commiserated with each other. We threw parties to keep warm. I especially remember a party hosted by a Peruvian couple, at which our Chilean friend was being the ideal guest—replenishing refreshments and taking dirty dishes into the tiny kitchen.

One evening I ran into her in the building’s lobby as she was returning from a nearby grocery store. Eyes wide and more animated than usual, she demonstrated how a thief had grabbed a bag of groceries from her cart as she was walking home. Then she shrugged and said, “It’s what happens in a big city.”

When the master’s program ended the following May, my friend and her husband returned to Santiago, Chile, and my husband and I moved to Reston, Virginia. We exchanged addresses and promised to keep in touch.

How I wish now that I had saved my friend’s letters! I especially regret not having kept her Christmas cards, each of which was a unique, hand-painted watercolor. I hadn’t known she was an artist. In the card she sent in 1973, mailed only months after the dictator Augusto Pinochet seized power, she wrote that a group of their friends had been rounded up and taken to the National Stadium. Even though I continued to send Christmas greetings for several years, I never heard from her again.

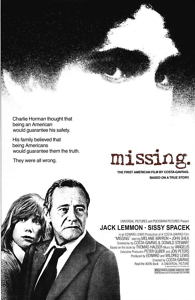

In the years since, I’ve seen the 1982 Costa-Gavras film, Missing, numerous times. Jack Lemmon plays Ed Horman, an American who goes to Chile to search for his missing son, Charles, who had been living happily there until the 1973 coup that put Pinochet in power. Both the film and the book on which it is based (Missing: The Execution of Charles Horman by Thomas Hauser) suggest that Charles was killed because he knew about his own country’s involvement in the dictator’s rise to power. In the movie, Charles, a writer, has the misfortune of being in the wrong place at the wrong time: on the eve of the coup, in a restaurant in Viña del Mar, he has a brief conversation with an American officer who brags about being involved in a top-secret mission.

In the years since, I’ve seen the 1982 Costa-Gavras film, Missing, numerous times. Jack Lemmon plays Ed Horman, an American who goes to Chile to search for his missing son, Charles, who had been living happily there until the 1973 coup that put Pinochet in power. Both the film and the book on which it is based (Missing: The Execution of Charles Horman by Thomas Hauser) suggest that Charles was killed because he knew about his own country’s involvement in the dictator’s rise to power. In the movie, Charles, a writer, has the misfortune of being in the wrong place at the wrong time: on the eve of the coup, in a restaurant in Viña del Mar, he has a brief conversation with an American officer who brags about being involved in a top-secret mission.

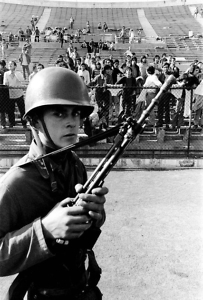

I can’t remember when or where I first saw Missing, but I do know why it has haunted me ever since: it’s the scene where Ed Horman goes to the National Stadium in Santiago, where thousands of Chilean citizens are being held, just as my friend had described in her Christmas card. In the film, Horman walks onto the playing field, yelling his son’s name over and over again to the people slumped in the stands. There is no reply. Charles is not there.

By the time Missing was released, I had become a librarian in Baltimore. The movie gave me a possible explanation for my friend’s silence, one I did not want to accept. If she and her husband had been friendly with the very people Pinochet had targeted, wasn’t it likely that they, too, had been arrested? Had my friend become one of Chile’s “missing?”

After completing a master’s degree in creative writing, I began writing a novel about a librarian whose best friend from childhood moves to Chile after college and marries a Chilean poet. The couple are put on Pinochet’s hitlist but manage to escape to the United States, where the husband publishes a book of poems unflattering to the dictator. Pinochet has the poet and his wife assassinated, leaving their three-year-old son an orphan.

After completing a master’s degree in creative writing, I began writing a novel about a librarian whose best friend from childhood moves to Chile after college and marries a Chilean poet. The couple are put on Pinochet’s hitlist but manage to escape to the United States, where the husband publishes a book of poems unflattering to the dictator. Pinochet has the poet and his wife assassinated, leaving their three-year-old son an orphan.

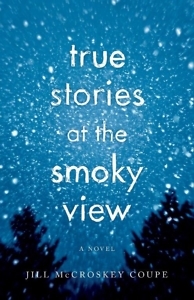

Unsure about how the story should end, I put that novel aside and began a new one. Eventually I returned to and finished the first novel. True Stories at the Smoky View was published last year. Would I have written the same book if I’d never encountered a friendly couple from Chile while living in New York City? Of course not. Worrying for years about a question with no answer is more than a little neurotic. It can also provide fertile soil for plot development.

I have tried, numerous times, to locate my friend. I did find her husband, an attorney in Santiago. Using his email address at the law firm where he worked, I wrote to him, asking if he remembered my husband and me from that year at NYU and mentioning that his wife and I had corresponded for several years afterward. I asked him for any news of her.

It’s entirely possible he didn’t receive my email. Or maybe he did read it and chose, for whatever reason, not to answer it. I’ve decided to respect his privacy.

Perhaps they, too, are divorced now, just as my former husband and I are. Could she have remarried and acquired a new last name, making it nearly impossible for me to locate her in cyberspace? I dearly hope the explanation is so simple.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Jill McCroskey Coupe. All rights reserved. Jill McCroskey Coupe’s first job was collating in her father’s printing plant in Knoxville. A former librarian at Johns Hopkins University, she has an M.F.A. in Fiction from Warren Wilson College. True Stories at the Smoky View was the 2017 Gold Medal Winner for regional fiction at the Independent Publisher Book Awards ceremony in June. The Southern Appalachians will always feel like home to her, but so does Baltimore, where she’s hard at work on her next novel.

Copyright (c) 2017 by Jill McCroskey Coupe. All rights reserved. Jill McCroskey Coupe’s first job was collating in her father’s printing plant in Knoxville. A former librarian at Johns Hopkins University, she has an M.F.A. in Fiction from Warren Wilson College. True Stories at the Smoky View was the 2017 Gold Medal Winner for regional fiction at the Independent Publisher Book Awards ceremony in June. The Southern Appalachians will always feel like home to her, but so does Baltimore, where she’s hard at work on her next novel.