Welcome to the Machine

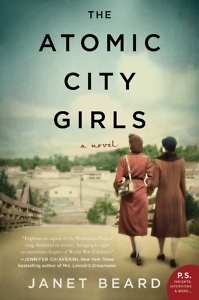

Characters come of age in the secret city of Oak Ridge in Janet Beard’s The Atomic City Girls

In an early chapter of The Atomic City Girls, the second novel from East Tennessee native Janet Beard, two young women walk down a city street, headed for a bowling alley after a day of tedious work. June, the protagonist, is eighteen and fresh off the farm. Her roommate, Cici, is a glamorous Nashville transplant. The city through which they walk, Oak Ridge, does not exist on any map, and the work they do is supposed to be kept secret, too, even from each other.

“So do you work at the same kind of machine as me, turning the knobs and watching the meters?”

“So do you work at the same kind of machine as me, turning the knobs and watching the meters?”

“Yes. Don’t worry, you get used to it.”

“Do you ever wonder about what the machines are doing?”

“June, it’s not safe to talk about that kind of thing!”

But talk about it they do, and so do other civilians employed by “Clinton Engineering Works,” the U.S. government’s code name for a sprawling base charged with generating fuel for the first atomic bomb.

As with June and Cici, the book’s other major characters are introduced by way of their unlikely kinships. Joe, a sharecropper from Alabama who sends money home to his wife and children, rooms with Ralph, a hot-headed teenager. Sam, a Cal-Tech physicist originally from New York, finds space in the home of Charlie, a graduate-school buddy, and Ann, Charlie’s young wife.

Their homes, like the work they do, illustrate the social stratification of Oak Ridge. Young women like June and Cici “watch the meters” and sleep in college-style dormitories, while African-American construction workers like Joe and Ralph live in “hutments,” windowless plywood boxes resembling the cabins of Japanese internment camps located elsewhere in the South. The scientific elite like Sam and Charlie enjoy prefab houses made of “cemestos,” a creative mixture of cement and asbestos.

Beard, whose grandmother and great aunt both worked on the Manhattan Project in Tennessee, did her research before attempting to recreate life in 1940s-era Oak Ridge. Some of the most fictional-seeming descriptions, such as a woman whose bobby pins fly out of her hair toward a uranium-enrichment machine, come directly from interviews Beard conducted with veteran plant workers. And even the more over-the-top details in The Atomic City Girls are supported by an unusual—but highly effective—sort of documentation for a novel: declassified Department of Energy photographs illustrate every chapter.

These images depict not only Oak Ridge’s hutments and cemestos houses but also smiling cashiers at the base Piggly Wiggly, happy crowds at square dances and movie theatres, nervous young women attached to lie detectors, and, especially, sign after painted sign reinforcing the secrecy of the place. The overall effect of Beard’s observant prose and these historic images is something akin to reading Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men while studying Walker Evans’s photographs of sharecroppers.

But despite its historically accurate physical details, the realm of The Atomic City Girls remains clearly fictional: character-driven and imaginative. Each character has strong personal motivations for taking work at the facility—some of which are realized, and some of which are dashed as the characters interact with one another.

But despite its historically accurate physical details, the realm of The Atomic City Girls remains clearly fictional: character-driven and imaginative. Each character has strong personal motivations for taking work at the facility—some of which are realized, and some of which are dashed as the characters interact with one another.

As they confront the complex hierarchy of Oak Ridge—especially its entrenched racism and sexism—each must lose some of the naiveté with which they first entered the base. Ralph becomes active with the Colored Camp Council, which organizes to improve conditions for African Americans, but he also gambles in the canteen. June learns secretarial skills and enters a torrid affair with Sam. As the book’s lower-level workers begin to suspect what the scientists have known all along—that the city exists only to build the most terrible weapon ever conceived—they all face separate moral dilemmas.

“What have we done, Charlie?” Sam asks his friend and fellow physicist when the bomb is tested in New Mexico. Charlie’s response: “Created a monster, I suppose.”

Later, June reads a banner headline in the Knoxville News Sentinel: “Atomic Super-Bomb, Made at Oak Ridge, Strikes Japan.” The characters Beard movingly portrays in The Atomic City Girls, like the country itself, are forever changed.

Michael Ray Taylor chairs the communication and theatre arts department at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia, Arkansas. He is the author of several books of nonfiction.