Reading Our Way Toward Otherness

A Memphis poet considers the legacy of his parents’ wise gift

At the close of the year I found myself thinking about one of the most wonderful, significant Christmas gifts I ever received. I was ten, and I got it because I didn’t get the thing I asked for first. My parents gave me a membership in the Book-of-the-Month Club.

What their first-semester fifth-grader had asked for was a large, color-plate book of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Japanese woodcut prints. I had fallen in love with it while prowling the shelves of the Highland Branch of the Memphis Public Library, where I was deposited one evening a week with my ninth-grade sister. I always made short shrift of homework, so while she toiled in the early forms of “research papers” I was free to wander through all the worlds at my reach, intriguing title by title, the unknown leading shelf by shelf to otherness. I don’t remember whether, when I took down a book—either as a possible check-out or simply to explore—I then sat near my sister. More likely, I stole off to some unoccupied table.

One night in November, this endless search brought me randomly to a particular book. I can see it. Probably about sixteen inches by eleven, a persimmon-rose-colored binding in something like silken jute, that I stroked gently like the extraordinary thing it was. I revisited it a couple of times, poring over the exotic drawings so unlike anything in my experience. When a couple of weeks later, around Thanksgiving, my parents first broached the subject of “wish lists,” I think I remember reverently pronouncing, like some sort of bibliophilic votary, “There’s only one thing I want.”

I don’t know the ensuing details. My mother at some point must have dropped by the library to see the book. And sometime soon thereafter I was let down gently. Though I don’t precisely remember their approach, I remember how kind they were. One evening after supper they sat me down and broke the news that the book wouldn’t be happening. But they didn’t make light of it. They didn’t say anything like, You’re ten years old and don’t need an art book of antique Japanese woodcuts. They didn’t cite the fact that the book was published by some posh house like Phaidon or Rizzoli in New York or London and (even in those days) cost a fortune, or that they wondered how long or how often I would actually enjoy it. They didn’t laugh, or even discreetly smile at one another.

They talked seriously to me, and with me, about my request. And they put forward an alternate proposition. Would I like a membership in the Book-of-the-Month Club, whereby I could choose a new book every month of the year?

I knew a non-negotiable “No” from my parents when I heard one, so I acquiesced, though the proposed substitute seemed a rather abstract notion—certainly not the rare and gorgeous bird I’d discovered on my own and actually held in my hand. But of course it turned out to be one of the most thoughtfully considered gifts of my life. They had respected my impulse but wisely also bought me some time. They gave me not one book but many, along with more long-lasting anticipation and the rights and responsibilities of choice.

Last year, when our grandchildren visited for Thanksgiving dinner and to see our new digs (a house inherited recently on the death of a cousin), eleven-year-old Emmett strode into the library, looked it up and down and all around, and said, “I’d like a room like this.” It’s where he chose to be during much of their twenty-four-hour visit.

My wife and I own a lot of books and now, after buying many from Cousin Gene’s estate, have even more—some of which of are handsome, richly colored, vellum-bound, gilt-lettered collectibles. The next morning Emmett and I were alone in the library, and he asked, “How many of these books would you say you’ve read?”

“Well, maybe not of these exact books but of these titles…. I don’t know, I’d guess about forty to fifty percent.”

He thought for a split second and said, “I think 100 percent would be a good goal for you.”

Emmett has always been a reader, and now thankfully seems to be growing out of a tendency, shared by many precocious children, to read “ahead of himself,” to skim. We stood together looking at the shelves and shelves of books, many with gilt piping and designs and lettering gleaming in the morning sun. In his eyes I saw at that moment the sheer pleasure we shared in them—and I recognized, from decades ago, a certain gleam of acquisitiveness.

I said, “I think you’re probably right. I’ve got two going now, but I have my work cut out for me, don’t I? Would you like to take one?”

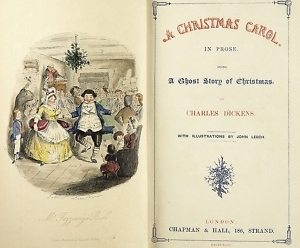

His father was already loading the car. They were about to leave. I riffed quickly around a few shelves. I saw Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, took it down and handed it to him. “You know it? You’ve seen a movie, maybe?”

“Just a cartoon version.”

“Well, I think you’ll like it. It’s the perfect time of year to read it. It’s about real people and it’s an excellent story.”

“Great.”

I inscribed it. The exchange felt, I think, pretty grown-up. At eleven, Emmett is perched astride the pre-teen chasm of wide-open ingenuousness and the first skeptical ironies of cool, but he seemed genuinely pleased, and when they got into the car a few minutes later he slung his carryall containing his various screen devices into the trunk and climbed into the backseat with the book still in his hand.

Next time perhaps we’ll have more time to look together at choices, talk over options. I only hope that over the years, whatever form libraries of the future may take, his eyes will continue to light up at the prospect of unread books, of their unique means of transportation—to learn more about himself and to cross the frontiers of geography, chronology, and culture to discover people and places he’s not yet even begun to imagine.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Hadley Hury. All rights reserved. Hury’s poetry has appeared in numerous journals, reviews, and magazines, and he is the author of a novel, The Edge of the Gulf and a collection of stories, It’s Not the Heat. He lives in Memphis with his wife, Marilyn Adams Hury.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Hadley Hury. All rights reserved. Hury’s poetry has appeared in numerous journals, reviews, and magazines, and he is the author of a novel, The Edge of the Gulf and a collection of stories, It’s Not the Heat. He lives in Memphis with his wife, Marilyn Adams Hury.