How Appalachian I Am

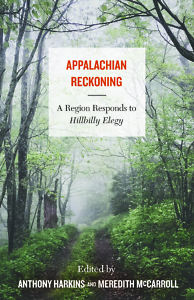

Book excerpt: Appalachian Reckoning

The building is stone. In one end of it, there is a liquor store. Beyond it, there is a mining camp, with rows of houses built by a coal company for its workers and their families. The liquor store is labeled, in letters painted on glass, Mongiardos. A five-foot man stands behind the counter. His hair lies in waves across the top of his head. The man smiles. There is a camera around his neck. The facing edge of the liquor store’s metal shelves carry, in red and black letters, the prices of the bottles of liquor. The facing edge of the shelves are lined with photographs of people taken in the liquor store, or in front of it. There are hundreds of photographs, pictures of coal miners with dust on their faces; pictures of politicians, smiling, with their arm around the man with the wavy hair; pictures of shirtless men with tattoos on their chests; pictures of women in prom dresses; pictures of young men in tuxedoes with their hair parted in the middle. The pictures are printed on paper. They seem, for the most part, to have been shot on film. These rows of pictures on paper tell the story of a drinking people. They are the feathers of a great, drunken bird.

* * *

The river that runs through Kingsport, Tennessee, generally looks green. A chemical plant sprawls along the river’s bank for nearly a mile. The plant sports smokestacks by the dozen, sets of stacks spread across acres. There is endless duct work curving and turning along the walls of the buildings, and between them. There are sheets of gray and green plastic, stories high and embedded with chicken wire, that serve as windows. The buildings are brick. Their smokestacks plume. Belts hiss, gears churn, and machines hum inside them. There is a smell of high school science labs run amok that fills the plant and spreads to the city and countryside around the plant. The smell is vinegary and invasive. One’s eyes water at the smell, until one grows used to it.

The river that runs through Kingsport, Tennessee, generally looks green. A chemical plant sprawls along the river’s bank for nearly a mile. The plant sports smokestacks by the dozen, sets of stacks spread across acres. There is endless duct work curving and turning along the walls of the buildings, and between them. There are sheets of gray and green plastic, stories high and embedded with chicken wire, that serve as windows. The buildings are brick. Their smokestacks plume. Belts hiss, gears churn, and machines hum inside them. There is a smell of high school science labs run amok that fills the plant and spreads to the city and countryside around the plant. The smell is vinegary and invasive. One’s eyes water at the smell, until one grows used to it.

The plant by the river made the chemicals used to make the film in the camera owned by the wavy-haired man peddling liquor. Thousands of coal miners and their families made it possible for the man with the wavy hair, and others, to make money selling liquor. Thousands of chemical workers made it possible for their picture to be taken. Every trip to Dollywood ever recorded on film, every wedding, every prom, every mug shot, every high school football game, every birthday party recorded in a photograph during the nearly hundred years when all photographs were recorded on film, was more than likely to have been enabled by a chemical made in that plant by the river in Kingsport, Tennessee.

The buildings in the chemical plant are numbered. The building numbered 190 once produced polyethylene and polypropylene pellets. Plastic pellets. Many of those pellets were sold to the company making film. But the machine operators in building 190 also produced plastic pellets for use by other firms. The pellets were shipped around the world, to factories where they were heated and molded into many things, including steering wheels and lawn mower parts, chain saw guards and tampon applicators.

The plastic was mixed in batches upstairs in building 190, in what were called Banbury mixers. Once mixed, the batches dropped into extruders which stretched the plastic into endless strands of brightly colored synthetic linguine. The extruders cooled the plastic pasta in long trays of water, and chopped it into pellets, which dropped into a box capable of holding a thousand pounds, or into larger metal hoppers. Boxes were sealed with metal straps and loaded onto a tractor trailer and taken to distribution, the part of the plant where product was shipped out. Hoppers were taken to the packing area, where they were set on a bagging machine that dispensed the pellets in fifty-pound increments into a double-thick paper bag. An operator set the bag to run through a sealer that glued the bag shut. The operator stacked the bags on a pallet, and the pallet was loaded on a trailer headed for distribution.

In the summers of 1983 and 1984, human beings operated the machines in 190. Human beings loaded the product. Human beings drove the forklifts. During the summers of 1983 and 1984, I was one of those human beings. I drove a forklift, sealed bags, strapped boxes, loaded product onto tractor trailers. Before I went to 190, the only paying work I had ever done was mowing yards. I mowed my family’s yard under duress from my father, and the rest of the yards on the street beside our house under duress from my mother. I went to work at the plant to earn more money, under less duress, and so the extruder operators and Banbury operators and shipping operators could take summer vacation.

One of the extruder operators was named Bear. Another was named Moon. They were both stout. They wore their coveralls open in the front. Bear wore safety glasses with clear frames surrounded by perforated plastic. Moon was bald, and had a salt and pepper beard. Bear’s beard was red. We were told to take brief but frequent breaks in a glassed-in room called the break shack next to the rods’ office. The rods are what we called the bosses. We would sit in the break shack and talk and smoke and rest. One summer, Bear and Moon helped me collect Planters peanut bar wrappers. If I saved fifty of them, I would be able to send off for a free Boomtown Rats album. Bear would fish wrappers out of the trash for me. I was very glad to be able to share my excitement about the Boomtown Rats with Bear and Moon.

One time when they got off second shift, Bear and Moon went frog gigging. They fixed tridents the breadth of a bullfrog’s shoulders to eight foot long golf course flagsticks. They walked that night beside creeks and ponds, with miners lights fixed to their belts, shining their lights at the water’s edge. When the light hit a bullfrog, his croaking stopped. “There he is,” one of them would say, and the flagstick fork would plunge into the frog’s back. Bear and Moon made a circle of a wire hanger, bent hooks in either end, and strung the frogs they caught on the wire, gouging it through the frog’s bottom jaw. When they returned to their vehicle with a gang of frogs on the wire, they took each frog and halved him at the waist with a big knife, saved the legs, and threw the rest in the weeds. They advised that one soak the legs in salt water before frying them, lest they jump out of the pan, looking for their lost frog.

One time when they got off second shift, Bear and Moon went frog gigging. They fixed tridents the breadth of a bullfrog’s shoulders to eight foot long golf course flagsticks. They walked that night beside creeks and ponds, with miners lights fixed to their belts, shining their lights at the water’s edge. When the light hit a bullfrog, his croaking stopped. “There he is,” one of them would say, and the flagstick fork would plunge into the frog’s back. Bear and Moon made a circle of a wire hanger, bent hooks in either end, and strung the frogs they caught on the wire, gouging it through the frog’s bottom jaw. When they returned to their vehicle with a gang of frogs on the wire, they took each frog and halved him at the waist with a big knife, saved the legs, and threw the rest in the weeds. They advised that one soak the legs in salt water before frying them, lest they jump out of the pan, looking for their lost frog.

The extruder operator named Bear is from Lee County, Virginia, which borders Harlan County, Kentucky. Once a young woman took a community college class in Harlan. I was her instructor, and required her to record an oral history. She recorded one with her father, who described for the young woman how his father, the young woman’s grandfather, a coal mine operator, had signed a seven-hundred-million-dollar contract to provide coal to the chemical plant in Kingsport. Seven hundred million dollars over thirty years is how the man on the recording put it. Many people in Harlan County mined coal, earned their living, to help that young woman’s grandfather honor that contract. Probably, many of them had their picture made during that time. Some probably drank liquor. I cannot say for certain. I do know this: Harlan County was mostly dry during the time of the seven hundred million dollars, and that the man with the wavy hair told me he sold liquor to Harlan County bootleggers during that time, including one, Mag Bailey, who, it is said, put several Harlan County lawyers through law school, and spent very little, if any, time in jail.

One gathers it is easy to die working in a coal mine, particularly an underground coal mine. Roofs fall. Ribs roll. There are explosives and thick cables carrying killing amounts of electricity. There are deadly and volatile gases. Miners need to be on their toes. Miners need to look out for each other. Miners need to know they can trust one another not to lose their heads. So they test one another. They do things like put motor oil in one another’s shampoo bottles. There are stories of them strapping young miners together, lip to lip, with electrical tape when they cannot get along, and leave them lying in mine passages until they kiss and make up. There are stories of nailing one another’s dinner buckets to the beltline. A miner who cannot tolerate this is not likely to keep his head when death comes knocking. That is the kind of thing most of us would like to know ahead of time, particularly if we knew we would be braving death on a daily basis.

It is not as easy to die on the job in a plastic factory as it is in a coal mine. But there is still danger. Once a man got his hand pulled off in a plastics extruder, and his coworker had to go back and get his wedding ring off a severed finger. And an inattentive operator can destroy tens of thousands of dollars of material in a minute by dropping a raw batch into an extruder, or taking too long a break and letting a hopper overflow onto the factory floor. And so there was hazing in the plastics factory too. For example, a forklift driver had to go outside to get pallets, on which all material was transported, at least once a shift. It was not unheard of for one’s fellow operators to fill the plastic bag that lined the thousand-pound boxes with water and drop it on a forklift operator’s head from the top of the building when he went out for pallets. The steel cage that covered the top of the forklift would protect the operator from a broken neck, but not the shattering of the bag and the “drowning” of the forklift operator by a hundred gallons of water.

Some of this hazing is meanness for meanness’s sake. Some of it is to stave off boredom. But there is also the lesson in the hazing that this is serious, dangerous work, and that a certain capacity for rough treatment is part of being able to stick with the job, part of being a reliable coworker.

Both the plastic factory that I worked in and most of the coal mines I have heard about are predominantly male workspaces. One need not have much imagination to recognize in the hazing a certain macho relish in being “tough enough” to endure the challenges of the job, and a certain amount of defending the space against those who might not immediately fit a relatively narrow definition of who can do the work. Both the mines and the plastic factory, as I have experienced them, are classic creations of industrial capitalism and of the particular strain of patriarchy supporting and supported by industrial capitalism.

* * *

My mother married when she was nineteen. She was twenty-four when I was born. My mother went back to college when I was old enough to look after my little brother. She went to East Tennessee State University and earned a degree and became a registered nurse. My mother was anxious about her own intelligence and her ability to graduate from college. She finished first in her nursing class. Her father was a vice-president at the chemical plant in Kingsport. Her mother never worked outside the home.

My father married when he was twenty-four. He graduated from the University of Tennessee, which he attended on a basketball scholarship. My father’s mother died when he was four. He was raised by his father’s sister, and then his father and stepmother. My father attended four different high schools in two states. His father was a storekeeper for the W.T. Grant Company. My father became a supervisor at the chemical plant. He managed the distribution of several warehouses worth of the raw material that goes into cigarette filters. He died, like many, many people in Kingsport, of cancer.

When my mother graduated high school, her parents sent her to college in northern Ohio, to a school chosen in part because of its distance from my father. When they got together anyway, there was a big wedding, and my parents received a set of silver from her parents as a gift. My mother always told me her mother told her they would get the silver engraved “if the marriage lasted.” It did. The silver remains unengraved.

My mother died in 2016. She once ate all the crème out of a pack of Oreos and fed the cookies to the dog while she was talking on the telephone. She once had a doctor wire her jaw shut to help her lose weight. She taught newborns to swim. She took in my cousins when they were in trouble and had nowhere to go, even when she did not agree with what they were doing. She took a job as the patient advocate at the hospital where she was born, and with unflinching diligence brought complaints about the medical care the hospital’s patients received to the people who could do something about it. When she retired, the hospital discontinued her position.

When my mother was a child, she and her twin brother were often sent to Erwin, Tennessee, to spend weeks at a time with their paternal grandparents and aunts. Once my mother had the mumps. She said it was the most miserable she had ever been. Her aunt Hazel asked what she could do to make her feel better, and my mother said, “Stand on your head,” which my aunt Hazel did. Another time, when my mother was eight, she went out to the coal pile in the back yard of her grandparents’ house in Erwin and found her grandfather sprawled across the coal pile dead. There were no other adults around, and so she told a neighbor, who sent her across the street to wait until the situation had been attended to. When my mother told me about it, she was incredulous that she had been sent away. She said, “What did they think I would see that was worse than what I had already seen?”

My mother harbored lawbreakers, spoke for the voiceless, confronted power, did what she thought was right no matter what it cost her, and perhaps most courageously, made her own sense of the world. Once near the end of her life, I was driving her to my brother’s house in Wise, Virginia, and a pickup truck drove by with a Confederate flag mounted in its bed. My mother watched the truck sail by, flag flapping in the breeze. She said, “Why would you do that when you know it hurts people’s feelings?”

My mother was at once the most fearless and the most nervous person I have ever known. For all the stands she took in her life, she also lived in constant conviction that our doom was nigh. If we did not call her on a semi-hourly basis, we had to be dead. If there was ice on any road anywhere in North America, we needed to stay home (unless we were coming to visit her). In her mind, there was no point to frog gigging, that only trouble could come from it. The same was true of drinking, staying out late, and venturing too far from Kingsport. She rarely traveled without taking her own food, and her favorite part of any vacation was getting home. Worry was the motor of her existence.

My mother loved jokes. She loved stories. She loved playing cards. She loved us all laughing around her table. A primary manifestation of her anxiety was that people in her presence could not possibly have a good time unless she vouchsafed that good time, either by telling a funny story herself or putting impossibly well-buttered food in front of us, or egging on one of us to be entertaining.

When she passed, the funeral took place in the same church where she was baptized and married. There were four hundred people there. My brother and I told all the funny stories on her we could think of. People were laughing and crying, out of their heads. She would have loved it. In the receiving line, we heard a bunch more stories we’d never heard. One woman told me that when she first moved to Kingsport, she went to her first Kingsport party, and when she walked in, there was a woman dancing on a table. Her hostess said, “Don’t worry. That’s Barbara Gipe. She doesn’t drink.”

* * *

My experience in the chemical plant made me want to live deeper in the mountains than Kingsport, and so, much to my mother’s chagrin, in 1989, I took a job at Appalshop, a media arts center in Letcher County, Kentucky. In 1997, I took a job at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Harlan County, Kentucky. As part of my work, I coordinated a community process that resulted in a $150,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to use the arts to respond to the prescription painkiller crisis in Harlan. Our group, which included students at my college, interviewed community members about the prescription opioid OxyContin, the other drugs being misprescribed and abused, and everything else. We took those interviews and, working with playwright Jo Carson, wrote a play called Higher Ground.

One of the women we interviewed grew up in a coal camp. Her momma is gone. And her daddy moves to another coal camp, leaving this woman and her brothers, all of them children, to fend for themselves. To make the rent, they run a card game, most of the players coal miners. The woman is asked how she keeps all these grown people playing cards from taking advantage of her. She replies they always keep a fire in the grate, and a poker in the fire, and if any of them came in on her, she would stab them right in the chest with that hot poker.

Another, younger, female interviewee comes from a family with plenty of money. This woman gets hooked on pills, is arrested, and has to go in front of the judge. The day she goes to court there is a room full of the accused there with her. Not all of them have plenty of money. The judge asks the woman, “What are you doing here? You’re not supposed to be here. You’re from a good family.” The woman says, “Everybody in there could hear. And I just wanted to say, ‘And they are supposed to be here? It’s OK for their lives to be ruined, but not mine?’ Drugs don’t care who you are. They treat everybody the same.”

The stories of these two women ended up in our first play. One of the things we try to explore in the first Higher Ground play is that perhaps we should respond to the drug crisis the way we respond to a flood in our community—collectively, instead of trying to work it out by ourselves. So in the script, we had the card game woman and the good family woman make common cause. But before they could make common cause, we had to find something they had in common. At the time, we had several stories floating around about people who were packrats, and we thought that would be good, because there are people of all classes and backgrounds who are packrats. So we made that the thing these two different unconnected women had in common.

To make the connection between these two characters, we used a story from my experience with my mother. One day I went with her to her safe deposit box. And in there with all her jewelry and money papers, there’s an umbrella and a bag of cheese doodles. She left them in there, she said, because one day she came in in a hurry, eating cheese doodles for lunch, and was embarrassed to walk out with them. I was worried that when my mother came to see the play, her feelings would be hurt by that story being in it. I asked her afterward what she thought of the play. She said, “Oh, Robbie, it was wonderful.” I asked her what she thought of the safe deposit box story. She said, “See, I told you I wasn’t the only one who does that.”

By the time we got to the sixth play, even though all the plays had good music and funny stories in them, people wanted something lighter. And so we decided to do a short play that was a funeral like my mom’s, where everybody told good, funny stories about the deceased. That play, which is called Life Is Like a Vapor, takes a character, Sweet Betty, who we introduced in our fifth play. Her funeral reveals that she has nearly died many times—she falls out of a deer stand when a woodpecker begins pecking her exquisitely camouflaged hand as it holds a tautly drawn bow; she lies about her weight at a zipline, then crashes the zipline and nearly crushes a youth choir; she gets castor bean pulp in her eye, giving herself a nasty twitch; and she nearly drowns, by insisting on a baptism when the water is too high and the current too swift, surviving by stealing food from raccoons washing their meals on a log next to the truck tire in which Betty has become lodged. We knitted these stories, some version of which might have happened to people we know, while sitting in a room at the community college where I work, telling stories, like the ancients, in a circle, where one story leads to another, where tears follow belly laughs, where the competition to entertain is friendly and mutually supportive—the best of spaces, the kingdom of God lit by fluorescents and fueled by corn nuggets from the Dairy Hut.

I wish my mother could have seen Life Is Like a Vapor. It is her kind of thing. She did live long enough to see me, encouraged by the reception our plays received, go to the Appalachian Writers Workshop at Hindman Settlement School and then to other writing workshops. She lived to see me publish a novel. She saw me read and get fussed over and written about. All this made her very happy. She wasn’t that happy about me going to Mongiardos or, really, being around liquor at all. I understand her point. But I am glad to have been there, because Mongiardos is gone, gone like film pictures, gone like my building 190, gone like most of the coal mine work.

Mongiardos wasn’t far from Hindman, and one summer we took new friends at the Writers Workshop to see it. That’s how we found out it was closed. The building was still there, but the windows were dirty, and the shelves were bare. Those pictures were so beautiful, all those lives caught at moments of greatest joy, darkest despair, and all points in between, and they had all disappeared.

I don’t know what happened to those pictures, the feathers of the great drunken bird. Maybe the bird flew away, its feathers intact, rising in wobbly glory above the ridgeline and into the mountain sky, landing somewhere safe, somewhere where there is a person to tell us all the stories of all the people. Maybe. Maybe I will drink less, so I can better remember all the things I have heard and seen, and be better able to tell it, and better able to listen with patience and care to the stories others are telling. Maybe. That would make my mother happy.

* * *

Well, to sum all this up and get to my topic, which is how Appalachian I am, I would say this: I reckon I’m more Appalachian than some, and less Appalachian than others. I’d say I’m Appalachian enough. I’d say I was raised, by both my mother and my father, to make my own sense of the world. And I was raised to make meaning by telling stories and listening to stories. I was taught that meaning is complex and shifting and difficult to state, and the more stories one adds to one’s thinking the harder it gets to make meaning, and that is good, and a good thing to keep in mind when one sees something new—that one won’t be able to make any sense of a thing until one hears not one but many stories about it. And I was raised to know that one good thing about stories is that one person might make one meaning out of a story and another person might take a different meaning from it. And I was raised to believe this ability to make our own meaning out of the world is what freedom is, and what joy is, and meaning making is a right we all have. I was raised that we all are obliged to work to make sure everyone has the right and the opportunity to tell their own story and hear everyone else’s—the easy story to hear and the difficult, the happy and the sad, the comic and the tragic. And we are all obliged to work to make sure each of us has the right to hear and tell all the stories and each make our own meaning out of them and the world, and if we don’t work toward that end, we are cheating our neighbor, and we are cheating ourselves of the joy of living, and should be ashamed of ourselves and should be forced to take long car rides in cars with no radio for all of eternity with people who grew up in places where they didn’t learn how to tell stories.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Robert Gipe. All rights reserved. Robert Gipe, author of the illustrated novels Trampoline and Weedeater, grew up in Kingsport. Since 1997, he has served as director of the Appalachian Program at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Cumberland, Kentucky. This essay appears in Appalachian Reckoning, a regional response to J.D. Vance’s controversial bestselling memoir, Appalachian Elegy. The collection will be published on March 1, 2019.

Copyright (c) 2018 by Robert Gipe. All rights reserved. Robert Gipe, author of the illustrated novels Trampoline and Weedeater, grew up in Kingsport. Since 1997, he has served as director of the Appalachian Program at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Cumberland, Kentucky. This essay appears in Appalachian Reckoning, a regional response to J.D. Vance’s controversial bestselling memoir, Appalachian Elegy. The collection will be published on March 1, 2019.