Unfixable Beauty

Ross Gay incites revolutionary thinking through sharing joy, fruit, and poetry

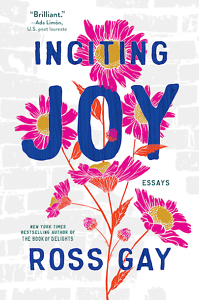

Bestselling author, poet, and professor Ross Gay is a devotee of the wild and wondrous elements that grow in the garden or the classroom and surprise us in poetry or community. His latest book, Inciting Joy, is organized around 14 reflections he calls “incitements,” with topics like accompanying a dying father, planting an orchard, playing pickup basketball, and unlearning white supremacy.

“[I]sn’t the point of beautiful art — again, like a person, like a life — that it is unfixable and unfixing? That it changes as we change?” writes Gay. When we escape the mastering mentality of what he calls the brutal economy, joy inspires us and we incite more joy in others. Gay draws on the ways that sports, gardens, literature, and companionship loose the shackles of capitalism’s productivity mindset and “rejoyn” us to gracious and life-giving ways of being.

In a chapter about the organization of a non-profit to start an urban orchard and plant trees that would not bear fruit within the lifetime of some of its board members, Gay reveals the beauty in volunteering together:

The inefficiency, the incompetence, the ineffectiveness, the dismal rate of production, the off-taskness, the wandering, the flabbiness, the consensussing, the play, the listening, the dreaming, were just ways of being together. It was hanging out, it was growing closer, it was mycelial, its product was itself, its product was connection, friendship, it was care, … that was the product, which is to say the product was our needs offered to each other, held to each other, held by each other.

The inefficiency, the incompetence, the ineffectiveness, the dismal rate of production, the off-taskness, the wandering, the flabbiness, the consensussing, the play, the listening, the dreaming, were just ways of being together. It was hanging out, it was growing closer, it was mycelial, its product was itself, its product was connection, friendship, it was care, … that was the product, which is to say the product was our needs offered to each other, held to each other, held by each other.

Each statement Gay makes chooses a syntax that is not sloppy but subversive. It is common in his prose to count eight commas, two em dashes, and a colon — or several semicolons and italicized phrases — before stopping in astonishment at the period. “And if you haven’t noticed, I am a fan of the digression,” Gay acknowledges in friendly candor. His prolific use of asides and footnotes reveals that he views the relationship between writer and reader as dialogical and evolving.

Like his philosophical propositions, Gay’s prose disrupts the paternalism, perfectionism, false objectivity, individualism, and other symptoms he sees as manifestations of white supremacy, especially in academic settings. He dances between the formal text and the informal subtext. Each chapter is written with first person narration but the footnotes, which can extend from half a page to nearly three, are offered in the second person direct address. In his commentary, Gay proposes playful challenges like “I have to tell you” and “You can tussle with the word [I used]” and “[N]ow go write your poem.” The equitable way that he cites friends, aunts, neighbors, comedians, and poets suggests Gay doesn’t seek to be a solo voice but a host for communal wisdom. His style, at times intentionally casual and unwieldy, is larger than stream of consciousness. His voice bubbles over like a buddy in the stream of conversation — invitational and infinite.

With joy as his muse, Gay tries not to be the lonely artist in search of an ideal but a community organizer inciting us to change what could destroy our capacity for greater connection and care for life. In a meditation on the dehumanization of school and the reclamation of learning through joyous bewilderment, Gay offers his ars poetica in rhythmic prose: “Don’t we often need and love, some of us anyway, that art asks more than we could ever answer … and in so doing, unfixes those of us who encounter it?”

The beauty of this book is not what happiness it helps us find but what mentalities and habits each incitement invites us to unfix. Joy, like beauty, cannot be produced by human beings who fixate on achieving it; joy must be stirred up within and between us.

Beth Waltemath is a writer and native Nashvillian. She currently lives in Decatur, Georgia. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Chapter16.