Ball of Fire

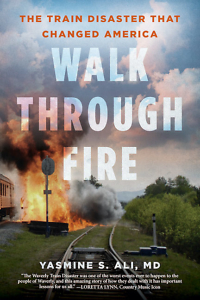

Book Excerpt: Walk Through Fire

FEBRUARY 24, 1978

FRIDAY

2:55 P.M.

The whole world had turned upside down.

Police Sergeant Elton “Toad” Smith looked up to see what had struck him on the forehead. What he saw made his blood run cold in spite of the sudden, searing heat. It seemed as if the entire railbed had been hurled into the sky, in one giant whirlwind of rocks the size of golf balls. Debris flew everywhere. Beams from buildings, metal from train cars. Even a hard hat whirled above him, leaving him to wonder about the head that had been wearing it. And surrounding it all were the never-ending billows of smoke, streaked through with blinding flashes of white.

Toad had run no more than three steps from his patrol car in the center of Waverly, Tennessee’s New Town section when he became aware that he was waist deep in an all-consuming blue flame that formed a wall for as far as he could see. This shimmering blue wall swept by and through him, engulfing everything in its path, marching all the way out to Commerce Street and passing in front of Slayden Lumber Company.

Oh, God, what a way to die, Toad thought. But then the blue flame simply disappeared, going out as quickly as it came, and Toad hoped that would be the end of it.

He kept running, picking up speed, knowing that he had to get out of there, put some distance between himself and the whirlwind of debris, or at the very least, get behind a building — preferably one that was still standing. As he ran, he became aware of a hideous noise ominously close to him, a sound he would never forget for the rest of his life. It reminded him of the sizzling sound a piece of raw meat makes when dropped into burning-hot oil. “Tshhh,” hissed this awful noise near his ear, and he involuntarily turned his head to locate the source.

The sizzling seemed to be coming from inside his own ears now, and as he turned and looked around, glancing behind him while still running parallel to the large front wall of Slayden Lumber, he saw the far end of the wall spontaneously combust. He watched in disbelief as it went up in one big fireball.

He was now almost to the end of that same wall, nearly to the right front corner of the massive Slayden Lumber building, the left end of which was going up in flames behind him, and he just kept thinking to himself, If I can get behind it, if I can just get behind this building, maybe I could stay out of it. Maybe I might have a chance.

When he got to the remaining front corner of the building, however, he found that the fireball had beaten him to it. He stood stock-still, watching in horror as that ball of fire rolled out in front of him. There was nowhere left to go, no place left to run. So Toad took one last look at the ball of fire, shut his eyes, and with the prayer “Lord, help us all” on his lips, ran right through it.

***

Most Americans have heard of FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency that coordinates the nation’s response to disasters, both natural and manmade. But few know its origin story.

From floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, and earthquakes to water contamination, Ebola, Zika, and COVID-19: FEMA has been there, as its mission states, “to help people before, during, and after disasters.”

And while most of us take FEMA’s existence for granted, a centralized, national agency for managing America’s large-scale disasters has not always been around. Prior to 1979, disaster response was carried out by a chaotic hodgepodge of state and local agencies and civil defense forces. However, the 1970s witnessed a rise in the number of disasters resulting in loss of life and significant property damage. Calls for better emergency response training and coordination grew louder until, in the latter part of the decade, the need could no longer be ignored. Ironically, one of the primary events that finally catalyzed the formation of FEMA began in a way that hindsight might consider entirely appropriate: with a freight train.

And while most of us take FEMA’s existence for granted, a centralized, national agency for managing America’s large-scale disasters has not always been around. Prior to 1979, disaster response was carried out by a chaotic hodgepodge of state and local agencies and civil defense forces. However, the 1970s witnessed a rise in the number of disasters resulting in loss of life and significant property damage. Calls for better emergency response training and coordination grew louder until, in the latter part of the decade, the need could no longer be ignored. Ironically, one of the primary events that finally catalyzed the formation of FEMA began in a way that hindsight might consider entirely appropriate: with a freight train.

An epidemic of freight train disasters and derailments has plagued North America in recent years, all of them devastating, many of them life-shattering. The July 2020 train derailment that sent a bridge to a fiery collapse in the Phoenix, Arizona, suburb of Tempe Town Lake, leaking hazardous material into the surrounding area. The July 2013 crash that destroyed the small town of Lac-Mégantic in the Eastern Townships region of Quebec, Canada, when a Montreal, Maine and Atlantic (MMA) Railway train carrying 7.2 million liters of crude oil jumped the tracks and exploded in the town’s core. The propane and crude oil train cars that burned for days in January 2014 when a Canadian National Railway train went off the rails in New Brunswick, Canada. The April 2014 derailment that plunged nearly 30,000 gallons of oil into the James River in Lynchburg, Virginia. The explosion near Baltimore, Maryland, in May 2013 when at least a dozen rail cars on a CSX train derailed after colliding with a truck, setting hazardous chemicals, including sodium chlorate, aflame.

But before Tempe Town Lake, before Lac-Mégantic, before New Brunswick, before Lynchburg, before Baltimore — before any of the dozens of train explosions all across the continent in the past four decades — there was Waverly. The Waverly Train Disaster of 1978 made news all over the world, as millions of television viewers, radio listeners, and newspaper readers literally could not avert their attention from the train wreck that consumed the heart of a small Southern town. It was the worst train explosion of its time, and most tragically, it was a disaster that never had to happen.

From the tiny epicenter of Waverly, Tennessee, the Waverly Train Disaster and its aftermath shook the globe, horrifying observers with the extent of its destruction and ringing alarm bells about train safety, hazardous materials handling, and disaster preparedness. Eventually, its aftershocks changed things for everyone everywhere, wherever there was an iron road, wherever train cars were made, wherever emergency preparedness officials drew up plans for disaster response.

The Waverly Train Disaster served as a catalyst for the establishment of FEMA, recommended by the National Governors Association just two business days after the disaster, and created by President Jimmy Carter’s executive order the following year, in 1979. FEMA’s origin story is included in the pages that follow.

A multitude of other changes in disaster management and training can also be traced back to what happened in Waverly. The Waverly Train Disaster has been labeled the “high-water mark of hazardous materials incidents in the United States” (Firehouse, 2003), one that has since been used as a model to train firefighters throughout the country. The creation of the Tennessee Hazardous Materials Institute in the wake of the disaster resulted in the development of new standards for hazardous materials (hazmat) handling and containment; the training program created by the Institute became a model for the nation.

Fallout from the Waverly Train Disaster also led to the passage of the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, which deregulated the American railroad industry in what is widely regarded as a rare win-win situation, one that allowed the U.S. rail freight industry to put itself on a more secure financial footing — which, in turn, led to implementation of much-needed safety changes for that time.

Additionally, the disaster led emergency managers to dramatically redesign training programs for emergency responders in order to place a focus on methods that reduce the risks to the responders themselves, thus protecting the lives of those who make the greatest sacrifice to help the rest of us when we need it most.

For decades since, the mere mention of Waverly has conjured memories of the train disaster for all who knew or heard of it and therefore associated the town with it, and for all who had learned the hard lessons of just how wrong things can go, and how fast, in the absence of correct safety measures and in the presence of faulty machinery. But at least as important as what went wrong that tragic day in Waverly was what went right — and therein lie the most promising lessons for the present. A number of infrastructural strengths existed in Waverly, and in small towns across America, that functioned as a counterbalance to the failings of the deteriorating railroads and the inadequate hazmat handling standards of the time. This book highlights these strengths in detail, in addition to the aforementioned actions that were taken after the disaster to improve rail safety and hazmat containment.

But in the end, after the tales of metal and machine have had their turn, we always, eventually, find that what it comes down to is the people involved. The people who lived, the people who died, the people who endured with uncommon bravery, who cleaned up the mess, and who were left to deal with the aftermath and all that entailed.

Excerpted from Walk Through Fire by Yasmine S. Ali, MD. Reprinted with permission from Kensington Books. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved. Yasmine S. Ali is a cardiologist and former president of the Vanderbilt History of Medicine Society. Dr. Ali grew up in Waverly and still lives nearby. She personally knows the survivors of the Waverly Train Disaster.