Fletch Inhaled Twice

Reflecting on the influence of I.M. Fletcher and his creator, Gregory Mcdonald

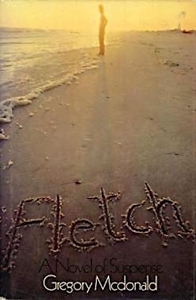

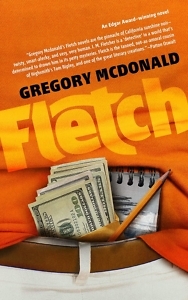

Fifty years ago, Gregory Mcdonald, a former Boston Globe journalist, published his first mystery novel, Fletch. The book won an Edgar award for Best First Novel, and Mcdonald’s wisecracking journalist (and later detective) spawned eight additional novels (the second, Confess, Fletch, also an Edgar winner), two spinoff series, and several films.

At the height of his career — shortly after the 1985 film Fletch, starring Chevy Chase — Mcdonald moved to rural Giles County, Tennessee, near Pulaski. The later Son of Fletch and Skylar mysteries both feature Southern scenes and characters that reflect his chosen home. Mcdonald continued writing there (and reportedly dabbling in local politics) until his death in 2008 from prostate cancer.

Beyond its commercial success, Fletch created a new genre, which, if it had a name, would be something like “gonzo comic mystery.” The essence of the form is a nonconforming, carefree protagonist with sharp wit and loose morals, who continually outsmarts the bad guys. Mcdonald’s Fletch presaged Hiaasen’s Skink and Tim Dorsey’s Serge Storms. The plot revolves around two mysteries: a narcotics investigation in which Fletch poses as a beach bum druggie and a millionaire who tries to hire the supposed beach bum to murder him for $50,000. As Fletch investigates both stories, he effortlessly harpoons stuffed shirts and bureaucrats while sidestepping police and lawyers. (Mcdonald said in later interviews that the character’s name came from a popular brand of arrows.)

Irwin M. Fletcher hates his first name. His news pieces are bylined I.M. Fletcher, and he goes by Fletch when possible. Despite a commitment to uncovering and reporting the truth, he continually violates accepted journalism practices, assuming false identities, hiding crimes from law enforcement, and having sex with married women he interviews. Fat Sam, a drug dealer crucial to Fletch’s investigation, sits with the reporter in a scene where the dealer knows police are closing in:

Fat Sam lit a joint and inhaled deeply. He handed it to Fletch.

“Peace.”

“Fuck.”

“That too.”

Fletch inhaled twice.

Fletch is an embodiment of what the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin termed carnivalesque — literature that destabilizes the existing power structures and social order. He resembles the trickster inhabiting the oral traditions of many cultures. “I’m a liar with a fantastic memory,” Fletch tells Fat Sam. But Mcdonald drew on a unique combination of classical education and a deep, personal understanding of the transformation wrought on American culture by the 1960s to make his ancient hero new. He was a writer in the right place at the right time.

A decade before Fletch, Mcdonald published his only previous novel, Running Scared, the moody story of a campus suicide that leads to an affair between the dead student’s sister and his best friend. The book received little attention (and a later British film made from it bombed), but it helped the author land a features gig at the Globe. From 1964 to 1971, he covered the rising counterculture, interviewing Joan Baez, Donovan, Abbie Hoffman, and Andy Warhol, among many others. Beyond the Harvard-educated writer’s deep dive into the decade’s luminaries, he did occasional investigative work for the Globe.

A decade before Fletch, Mcdonald published his only previous novel, Running Scared, the moody story of a campus suicide that leads to an affair between the dead student’s sister and his best friend. The book received little attention (and a later British film made from it bombed), but it helped the author land a features gig at the Globe. From 1964 to 1971, he covered the rising counterculture, interviewing Joan Baez, Donovan, Abbie Hoffman, and Andy Warhol, among many others. Beyond the Harvard-educated writer’s deep dive into the decade’s luminaries, he did occasional investigative work for the Globe.

“I can remember sitting around the city room at 3 a.m. listening to the reporters tell stories,” he told mystery novelist Lee Goldberg in an early interview. “There’s a real spirit there.” In the same interview, Mcdonald said he was sure that his irreverent novel “had no chance of succeeding.” While heading off for a family vacation, he casually sent the finished manuscript to his former Globe copy boy, saying, “If you like it, do something with it.” His junior colleague liked it and soon found a publisher.

That newsroom spirit appears in a later chapter: “In all newspapers Fletch had seen there was always a hard core of genuinely professional working staff which made it possible to commit genuine journalism occasionally, regardless of the incompetence among the executive staff.” Not that Fletch engages in much self-reflection. About 90% of the novel (and those that followed) is comic dialogue, pages of it that ring true today while advancing plot and revealing character. Mcdonald only occasionally interrupts the funny talk with a line or two of crisp action, as required.

“I work very hard at being simple,” he told the crime novelist Bruce DeSilva in 1986, citing the many thousands of hours of film and television seen by the average 18-year-old. “Where Sir Walter Scott used 7,000 words, I can get it down to seven by conjuring the images that are already there.” Mcdonald’s ability to simplify prose while conjuring a classic hero makes Fletch not only fun to read, but timeless, as evidenced by the 2022 film Confess, Fletch, starring Jon Hamm. While technology and journalism ethics have changed since the book appeared, Fletch retains a current feel.

The sole exception may be the lead character’s treatment of women. “In the great mystery novels of the ‘30s and ‘40s, the woman was either a Madonna or a doll,” Mcdonald told DeSilva in 1986. “Neither Fletch nor Flynn [a spinoff protagonist] have this regard for women. Women are their equals, their friends.” While the author undoubtedly embraced this enlightened attitude, the first Fletch novel doesn’t always reflect it: Fletch hates his female boss and delights in undermining her. In his late 20s, he has been divorced twice but never pays alimony. He misleads both ex-wives into believing that he wants each to move back in with him, planning for them to arrive at a time he is to appear in court. He tries ostensibly to rescue a 15-year-old heroin addict and prostitute — by having her stay with him in his undercover identity’s crappy apartment. In short, Fletch can come off as a stereotypic 1960s chauvinist pig.

Amid the entertaining prose that fills the book, such elements can be jarring when they pop up in 2024. Yet as Fletch solves the mysteries, evades the cops and lawyers, and lucks into the cash, even offput contemporary readers may start to grin, willing to forgive the trickster and jump into the next book.

Michael Ray Taylor is the author of Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves. He lives in Arkansas.