A Dark Little Flame

Set in Sewanee, Leah Stewart’s new novel is a study of small-town secrets and hidden judgments

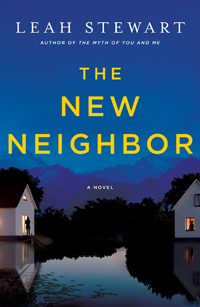

“There are only so many reasons to live in this place, in the woods, in the tiny towns,” reflects Margaret Riley, the ninety-year-old woman at the heart of Leah Stewart’s new novel, The New Neighbor. This particular tiny town is the Tennessee mountain community of Sewanee, where Margaret has come to live. Though she holds secrets tight within her, to all appearances she’s just an old woman bent on privacy, an “elderly evacuee of the working world.” But Margaret’s curiosity is sparked when a young mother and her four-year-old son move into a house visible from hers: Sewanee is not the sort of place where young families are likely to establish roots. What, she wonders, are this woman and her child doing here?

The woman in question is Jennifer Young, guarded and melancholy, on the run from her own past and a world that has shut her out. A massage therapist in need of new clients, Jennifer is forced to venture tentatively into her new community, where her path soon crosses with Margaret’s. In Jennifer, Margaret senses a fellow keeper of secrets. She also pegs the younger woman as a willing listener, the person to whom she feels compelled to unburden herself at long last—to share the story of what happened to her as an Army nurse during World War II.

The woman in question is Jennifer Young, guarded and melancholy, on the run from her own past and a world that has shut her out. A massage therapist in need of new clients, Jennifer is forced to venture tentatively into her new community, where her path soon crosses with Margaret’s. In Jennifer, Margaret senses a fellow keeper of secrets. She also pegs the younger woman as a willing listener, the person to whom she feels compelled to unburden herself at long last—to share the story of what happened to her as an Army nurse during World War II.

Stewart draws these two women together quickly, but her deliberate and gradual unveiling of their respective troubles—a twin set of unraveling mysteries—moves the novel forward. Both women have chosen to live at a remove; both are mostly estranged from family. Margaret, hungrier for attention and companionship than she believes, adopts a sleuth’s fascination with her taciturn new neighbor. Jennifer has her own curiosities and doubts about Margaret, but she’s disturbed by the reflection of herself she sees in the older woman’s “prickly isolation.” What’s keeping her from becoming similarly so marooned? Only her son, she thinks—only Milo.

Indeed, Milo is Jennifer’s sole link to the small world of young families who do reside on the Mountain—mostly those of professors at the University of the South. One of them, Megan, befriends Jennifer and turns out to be the mother of a child in Milo’s preschool class. She coaxes Jennifer out of her shell and into play dates and girls’ nights. And it’s soon clear that Megan too has her secrets.

The tenuous bond between Megan and Jennifer gives the novel an additional layer of intellectual intrigue. Though The New Neighbor is driven by suspense as buried pasts are finally revealed, Stewart also offers the thrill of sharp realism that has characterized her previous novels, including Husband and Wife and The History of Us. She’s skilled at creating characters who are all too recognizable in their foibles and desires; she dissects the way ordinary, flawed people think of one another and their social spheres—the silent preferences and judgments that accompany any interaction. Her depictions of a cocktail party at Megan’s house, or of the monthly girls’ night out at a local bar, are almost uncomfortably spot-on.

The tenuous bond between Megan and Jennifer gives the novel an additional layer of intellectual intrigue. Though The New Neighbor is driven by suspense as buried pasts are finally revealed, Stewart also offers the thrill of sharp realism that has characterized her previous novels, including Husband and Wife and The History of Us. She’s skilled at creating characters who are all too recognizable in their foibles and desires; she dissects the way ordinary, flawed people think of one another and their social spheres—the silent preferences and judgments that accompany any interaction. Her depictions of a cocktail party at Megan’s house, or of the monthly girls’ night out at a local bar, are almost uncomfortably spot-on.

Through Jennifer’s ambivalence about her friendship with Megan, Stewart portrays a woman who is acutely aware of the ways in which she can never be just one of the girls, the life of the party—she’s just not the sort to go in for forced camaraderie. But she does want, Stewart writes, “to will into existence the possibility that she can be different. What the other women do she will do, so that no one looking at the group could tell her apart from the rest of them.”

The New Neighbor is a thoughtful study of the masks we wear and the complex fictions we present to others, intentionally or by default, whether we like it or not. Who is working harder to conceal the self—the women who turn from society, their secrets held fast within, or those who go forth and circle others around them, defying anyone to pull back the curtain? And in a world where we are so desperately quick to judge, don’t we all face a jury of our peers? Both Megan and Jennifer have their demons; they just accommodate them in very different ways. “We’re all a little morally ambiguous, Megan,” thinks Jennifer as the two hike up to the famous cross in Sewanee. “Maybe, as it turns out, even you. We all have a dark little flame.”

Susannah Felts is a writer, editor, and educator in Nashville, as well as co-founder of The Porch Writers’ Collective, a nonprofit literary center. She is the author of This Will Go Down On Your Permanent Record, a novel, and numerous journal and magazine articles.