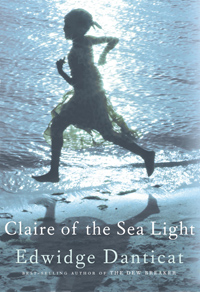

A Fable of Modern Haiti

In Claire of the Sea Light, Edwidge Danticat explores the secrets of a small Haitian town

Since publishing her first novel, Breath, Eyes, Memory, in 1994, Edwidge Danticat has become the literary voice of the Haitian diaspora, at least in the English-speaking world. She’s won wide acclaim for her stories and novels, as well as her 2007 memoir, Brother, I’m Dying, and she is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship — the so-called “genius” award. Born in Haiti and raised there by her extended family until she joined her parents in the U.S. when she was twelve, she’s a writer who can interpret both cultures, and she has a keen eye for the tensions between them. Claire of the Sea Light is a slim novel set entirely in a small coastal town in Haiti, with a story centered on the fate of a motherless little girl. The book explores the interconnected lives of the town’s inhabitants, yet even within this intensely local narrative, questions of exile and cultural identity are often hovering in the background.

The town of Ville Rose—when viewed from the nearby mountain, its perimeter looks like “the unfurling petals of a massive tropical rose”—is home to a handful of wealthy people, but most are poor, and among that impoverished majority is Nozias Faustin, a fisherman. As the novel opens, Nozias witnesses the death of an old friend, Caleb, who was swept out to sea in a freak wave. This tragedy darkens an already weighty day for Nozias: it is both the anniversary of his wife’s death and the seventh birthday of his daughter, Claire. Nozias has been trying, in spite of great misgivings, to persuade a prosperous fabric merchant, Madame Gaëlle, to adopt Claire and give her a better life than he can provide. That night, as everyone gathers on the beach to honor Caleb, Madame Gaëlle agrees to take Claire, and Claire reacts by running away.

The town of Ville Rose—when viewed from the nearby mountain, its perimeter looks like “the unfurling petals of a massive tropical rose”—is home to a handful of wealthy people, but most are poor, and among that impoverished majority is Nozias Faustin, a fisherman. As the novel opens, Nozias witnesses the death of an old friend, Caleb, who was swept out to sea in a freak wave. This tragedy darkens an already weighty day for Nozias: it is both the anniversary of his wife’s death and the seventh birthday of his daughter, Claire. Nozias has been trying, in spite of great misgivings, to persuade a prosperous fabric merchant, Madame Gaëlle, to adopt Claire and give her a better life than he can provide. That night, as everyone gathers on the beach to honor Caleb, Madame Gaëlle agrees to take Claire, and Claire reacts by running away.

This moment of crisis for Nozias, Claire, and Madame Gaëlle becomes the temporal anchoring point for a complicated narrative of love, loss, murder, and revenge that involves a cast of characters from across the socioeconomic spectrum of Ville Rose, including a schoolmaster, his son, his servant, a popular radio talk-show host, and a crew of gangsters. The town is revealed to be a web of relationships that transcend class and social divisions. The one reliable dividing line is between the denizens of Ville Rose and its exiles, who come back to visit “fatter and reeking of citronella, every mosquito and salad and untreated glass of water suddenly their mortal enemy.” The emigrants who return seem ashamed: “[T]heir eyes always betrayed them. All the humiliation they had endured could be detected there.”

The multiple plot lines lead back, directly or indirectly, to the gathering on the beach, and by the time the novel returns there, ugly secrets have been revealed about almost everyone except Nozias and little Claire. They are the innocents of the tale, and they seem to represent some elemental goodness in Ville Rose, which itself can be seen as a microcosm of Haiti. In Nozias’s memories of his wife (also named Claire), the novel gives its sole depiction of pure, untroubled love, and the child of that love is blessed by it.

The multiple plot lines lead back, directly or indirectly, to the gathering on the beach, and by the time the novel returns there, ugly secrets have been revealed about almost everyone except Nozias and little Claire. They are the innocents of the tale, and they seem to represent some elemental goodness in Ville Rose, which itself can be seen as a microcosm of Haiti. In Nozias’s memories of his wife (also named Claire), the novel gives its sole depiction of pure, untroubled love, and the child of that love is blessed by it.

She’s blessed, as well, by the beauty of her birthplace. Little Claire is called Claire Limyé Lanmé—Claire of the Sea Light—because her mother swam in a glowing patch of phosphorescence one night while pregnant with her. Claire knows the sea is the source of both life and death, and even though she is terrified of losing her father to it, she recites to herself a litany of all she would miss if it were gone, including “the turquoise in the distance and its light-blue ripples up close, the white foam at the peaks of the waves. She would miss the surge of high tide and the retreat of low tide, the milky or rosy clouds of dawn and the orange mists of sunsets.” Through Claire, the novel becomes a paean to whatever is sacred in the earth and water of this particular place, distinct from all others.

Claire of the Sea Light is written in the delicate, poetic style that Danticat is known for, which lends this story a fable-like quality in spite of the elaborate plot and the elements of modern mayhem it entails. The book asks some patience of the reader as it pulls together all its narrative strands, but it ultimately delivers a rich story that provides a glimpse of modern Haiti, as well as a sense of its enduring spirit.

Edwidge Danticat will discuss Claire of the Sea Light at the Nashville Public Library August 28, 2013, at 6:30 p.m.